I know, I know. I never post. I never call. I don’t bring you flowers. It’s a wonder we’re still together. I have the usual list of excuses:

1) GRADUATE SCHOOL

But before I disappear off the face of the interwebz once again, I thought I share with you a quickie post on the science behind our current Dietary Guidelines. Even as we speak, the USDA and DHHS are busy working on the creation of the new 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which are shaping up to be the radically conservative documents we count on them to be.

For just this purpose, the USDA has set up a very large and impressive database called the Nutrition Evidence Libbary (NEL), where it conducts “systematic reviews to inform Federal nutrition policy and programs.” NEL staff collaborate with stakeholders and leading scientists using state-of-the-art methodology to objectively review, evaluate, and synthesize research to answer important diet-related questions in a manner that allows them to reach a conclusion that they’ve previously determined is the one they want.

It’s a handy skill to master. Here’s how it’s done.

The NEL question:

In the NEL, they break the evidence up into “cardiovascular” and “diabetes” so I’ll do the same, which means we are really asking: What is the effect of saturated fat (SFA) intake on increased risk of cardiovascular disease?

Spoiler alert–here’s the answer: “Strong evidence” indicates that we should reduce our intake of saturated fat (from whole foods like eggs, meat, whole milk, and butter) in order to reduce risk of heart disease. As Gomer Pyle would say, “SUR-PRIZE, SUR-PRIZE.”

Aaaaaaaand . . . here’s the evidence:

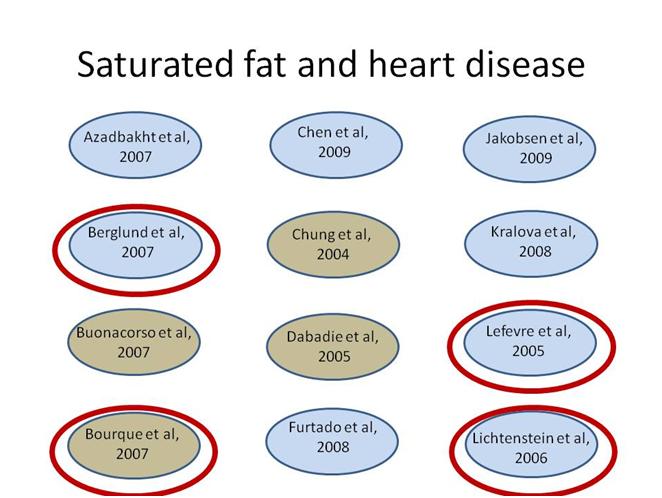

The 8 studies rated “positive quality” are in blue; the 4 “neutral quality” studies are in gray. The NEL ranks the studies as positive and neutral (less than positive?), but treats them all the same in the review. Fine. Whateverz.

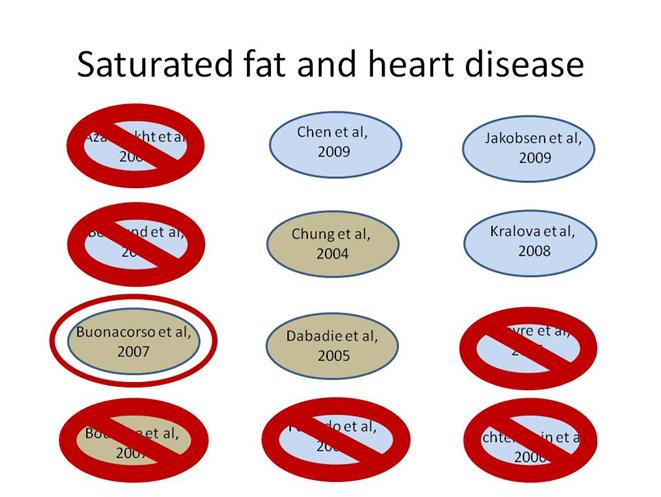

According to the exclusion criteria for this question, any study with a dropout rate of more than 20% should be eliminated from the review. These 4 studies have dropout rates of more than 20%. They should have been excluded. They weren’t, so we’ll exclude them now.

Also, according to NEL exclusion criteria for this question, any studies that substituted fat with carbohydrate or protein, instead of comparing types of fat, should be excluded. Furtado et al 2008 does not address the question of varying levels of saturated fat in the diet. In fact, saturated fat levels were held constant–at 6% of calories–for each experimental diet group. So, let’s just exclude this study too.

One study–Azadbakht et al 2007–was conducted on teenage subjects with hypercholesterolemia. Since the U.S. Dietary Guidelines are not meant to treat medical conditions and are meant for the entire population, this study should not have been included in the analysis. Furthermore, the dietary intervention not only lowered saturated fat content of the diet but cholesterol content too. So it would be difficult to attribute any outcomes only to changes in saturated fat intake. The study should not have been included, so let’s take care of that for those NEL folks.

In one study–Buonacorso et al 2007–total cholesterol levels did not change when dietary saturated fat was increased: “Plasma TC [total cholesterol] and triacylglycerol levels were NS [not significantly] changed by the diets, by time (basal vs. final test), or period (fasting vs. post-prandial) according to repeated-measures analysis.” This directly contradicts the conclusion of the NEL. Hmmmm. So let’s toss this study and see what’s left.

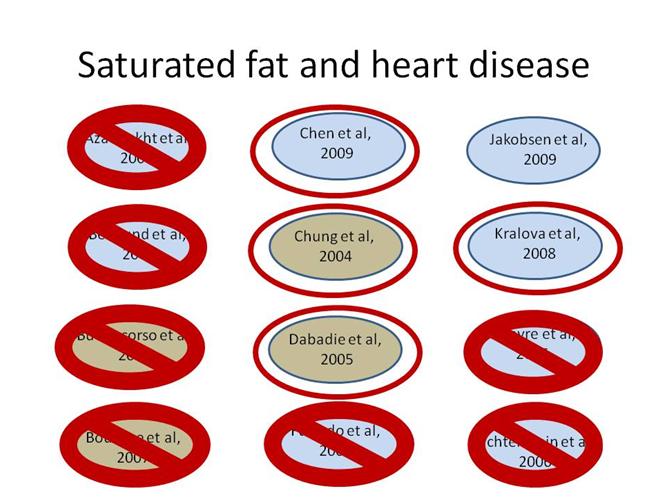

In these four studies, higher levels of saturated fat in the diet made some heart disease risk factors get worse, but other risk factors got better. So the overall effect on heart disease risk was mixed or neutral. As a result, these studies do not support the NEL conclusion that saturated fat should be reduced in order to reduce risk of heart disease.

That leaves one lone study. A meta-analysis of eleven observational studies. Seeing as the whole point of a meta-analysis is to combine studies with weak effects to see if you end up with a strong one, if saturated fat was really strongly associated with heart disease, we should see that, right? Right. What this meta-analysis found was that among women over 60, there is no association between saturated fat and coronary events or deaths. Among adult men of any age, there is no association between saturated fat and coronary events or deaths. Only in women under the age of 60 is there is a small inverse association between risk of coronary events or deaths and the reduction of saturated fat in the diet. That sounds like it might be bad news—at least for women under 60—but this study also found a positive association between monounsaturated fats—you know, the “good fat,” like you would find in olive oil—and risk of heart disease. If you take the results of this study at face value–which I wouldn’t recommend–then olive oil is as bad for you as butter.

So there’s your “strong” evidence for the conclusion that saturated fat increases risk of heart disease.

Just recently, Frank Hu of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee was asked what we should make of the recent media attention to the idea that saturated fat is not bad for you after all (see this video at 1:06:00). Dr. Hu reassured us that, no, saturated fat still kills. He went on to say that the evidence to prove this, provided primarily by a meta-analysis created by USDA staffers (and we all know how science-y they can be), is MUCH stronger than that used by the 2010 Committee.

Well, all I can say is: it must be. Because it certainly couldn’t be any weaker.

I am so glad to have stumbled across your blog! I am a dietetic intern on my way to becoming an RD and have been independently examining the case for paleo/primal/ancestral nutrition after being introduced to it by an RD 10 months ago. I love how you broke down the “evidence” for the DGA and look forward to investigating further.

It has been a struggle finding motivation to continue pursuing the RD credential in spite of the misdirection that continues to take place at all levels of the nutrition field. Thank you so much for giving me reassurance and hope!

By the way, I found your blog after googling “nutrition paradigm shifts” in search of a topic for a research presentation. Had I not read that article first, I probably would not have left a comment but instead continued on as a silent follower not helping at all with the movement. Everything truly happens for a reason =).

Keep up the good work!

Thanks for all the kind words & I’m glad you found the blob 🙂 Good news, there’s a “Real Food” RD group on facebook–discussing Paleo and other stuff–if you haven’t found it already: https://www.facebook.com/groups/434696973228157/

There’s all kinds of RD renegades out there! Let me know if you need any help finding material for you nutrition paradigm shifts research.

You cannot be serious! 😀

After reading this recently, “De Testimonio: on the evidence for decisions about the use of therapeutic interventions”, http://www.clinmed.rcpjournal.org/content/8/6/579.full.pdf+html, how can anyone reasonably believe in supposed evidence anymore, even RCTs???

Here’s a great quote:

The above lecture/paper is just too good, exploding the special status of RCTs and delving into Bayesian statistics as opposed to the normal frequentist approach, along with so many other insights about so-called evidence.

What good is evidence-based medicine/practice/guidelines if all your evidence is crap?

Here’s another take on the value (or lack thereof) of arranging types of science in a hierarchy according to their status as evidence of an empirically-discovered “truth,” by Craig Hassel at the University of Minnesota. I think there are some connections between this and your work, Kenny. http://www.nutritionj.com/content/13/1/42

Thanks, Adele. I really like this paper by Hassel. You’re right, I see the connections between what he discusses and some of my ideas. He throws around a lot of big words and ideas all throughout the paper but it still remains quite readable, which impresses me along with the content.

He writes, “And how is the discipline of nutrition science equipped to deal with concepts of human well-being seen as something independent of pathology or beyond the bio-markers of disease prevention?” which really hits home with me.

He also writes, “Cognitive frameshifting [38] is a developmental ability and an advanced intercultural skill that may be unfamiliar to many nutrition professionals” which sounds like he’s saying many nutrition professionals don’t know how to think outside the box. And after watching some of the video of the DGAC 2015 meetings (thanks to your pointing out the link above), I have to agree. They’re all in their own world. Why don’t they all try eating different diets and see how it feels? instead of telling us what’s supposed to work.

My take is that nutrition science has become too theoretical, straying from the practical knowledge gained from lived experience. Even though RDs should be at the forefront of practical application, they seem to rely mostly on the theoretical frameworks of what foods and diets are supposed to work, not what actually does.

And Hassel also asks, “What is the meaning of a “new nutrition science”? What exactly is meant by “a broader definition, additional dimensions and relevant principles”?” My vision is a new sub-field of nutrition that I call Behavioral Nutrition, based on empiricism, how the body actually behaves and responds to what you put in it, how it is processed (digested, absorbed, metabolized), what comes out, and how you feel all along the way – round-trip nutrition, holisitic. It’s focused on the practical rather than the theoretical, reductionist, nutritionism-istic standard model/view of nutrition science.

Instead of believing in lipid theory, energy balance theory, and so on, let’s be empirical, and eat what works,

empirical 1. adjective – derived from experiment and observation rather than theory

Behavioral Nutrition: I like it. I like the focus on eating and the body, rather than food and a numerical summary of its components. Eat what works (for you). I like that a lot 🙂

Hassel makes the point that “every society has had to develop its own understandings of food and health relationships,” and societies had been doing that for ages before science came along. There’s some humility to be recaptured and some refocusing to be learned from that. I love science. We’ve learned much about how to nourish ourselves from science. But when we reflexively privilege a scientific “Truth” over embodied experience, we’ve lost our way. Time to think again.

Dear Adele

GREAT post. We read you regularly.

Every one seems to forget that Willett and Hu use New Epidemiology. They never heard of “removing the pump handle.”

See:

http://ketopia.com/new-epidemiology/#more-1902

http://ketopia.com/epidemiology-misunderstood-misused/#more-2034

Thanks for the kind words and for the links. I’m feeling a little starstruck as I have enjoyed your most recent edition of The Modern Nutritional Diseases immensely. (I give out copies as gifts, a hazard of having a nutrition geek for a friend).

Yes, there are all kinds of problems with the New Epidemiology, and difficulties “removing the pump handle” is perhaps the most egregious one. A biostats professor at UNC-Chapel Hill has told me that, at this point, he has come to think that any epidemiology of chronic disease is likely to be highly flawed (for all the reasons mentioned in the links), not just nutrition epidemiology of chronic disease. One of the issues that I consider to be central to the problem of nutrition epidemiology of chronic disease (and all New Epidemiology) is one that you touch on at the end of this piece–and it is quite brilliantly stated:

[Emphasis mine].

More generally, without the more rigorous step of “removing the pump handle,” epidemiologists can “discover” all sorts of associations and propose all kinds of relationships of risk–which then get used to create or bolster policy and practices–without ever being held accountable for a bad guess. A practice backed by an observational study then becomes self-reinforcing as “the worried well” (who tend to be better educated, wealthier, and more Caucasian) adopt those practices. Those who don’t adopt those practices or don’t fully adopt them–whose health may be adversely impacted not by their lack of interest in health, but by factors outside of their direct control–are then blamed for not being responsible for their own health.

Alice and Fred, the articles you wrote on epidemiology are brilliant! Thanks for sharing them. For the last year or so, I have looked into the foundations of what you call “New Epidemiology” and seen what a total mess it is. New Epidemiology has vastly overstepped the scope of applicability of epidemiology and continues charging forward making unjustifiable claims about risks and causes.

We seem to be totally screwed with the field of Public Health seemingly based on this New Epidemiology. We need all you enlightened MPHs to fix this. Is that asking too much? 😉

It might be asking too much, but we’re going to fix it anyway. What else are we doing? 🙂

Dear Adele and Kenny,

We were very pleased with your kind responses to our epidemiology posts. It warms our hearts to find others who are really concerned about the problem. And thank you Adele, for reading our book.

We recall, Adele, that your graduate work is in nutritional epidemiology. We admire your choice. It is a very rigorous and demanding field and (as you know) involves great numbers and complexities of variables.

Kenny, you are obviously well versed in the field, too. We are sure you agree with Adele that the problem must be fixed.

To both of you, if and when you have time, we would enjoy very much hearing your thoughts.

“I’m still quite puzzled about the widespread enthusiastic uptake in the first place.” I think it’s not as mysterious as it might be; despite our inclination to criticize the government most people want to trust it. Who sees the doctor the most? Older people. Who listens to the government advice with the most dedication? Older people? Who gets a Social Security check every month on the dot? Every older person in this country has repeated, firsthand experience with one aspect of the government that they feel helps them out (despite the complaints about lack of reasonable COLA increases) and those checks have bought a lot of credibility. And I’m not criticizing Social Security here at all; I think it’s great as far as it goes. Money talks…in many directions.

Great to see another post from you; please try to drop in more often. 🙂

I agree with your point. I do see some generational differences, but they are not as clean cut as I thought they would be when I first started looking at this issue. Some older folks were skeptical then and remain skeptical now, but the key here is that they seem to have had some awareness of WW2 rationing that prioritized meat and eggs as foods to be used sparingly–in order to save them for the troops. The most susceptible group–this is just my collection of observations–seems to be the baby boomers who, emerging from the aftermath of the 60s, really wanted to believe that (as my husband puts it) “the hippies had won.” The vegetarian ideology captured in the 1977 DG seem to indicate that this perhaps was the case.

As a counterfactual example, I try to imagine if the 1977 DG would have even happened at all without a vegetarian-leaning belief system behind it. Thoughts, anyone?

Thank you so much for all your research and for taking the time to clarify what their “scientific” studies are saying.

Reblogged this on The Science of Human Potential and commented:

An excellent read examining the state of the evidence against saturated fats in the diet and health risk

There is actually something called the “Information Quality Act” which is supposed to ensure that scientific information on a federal website is accurate. Members of the public can write in and say that they think something is inaccurate. Not just that you ‘disagree’ but that something is factually incorrect. The agencies are required to respond and the response is also supposed to be public.

This would not be a place for sarcasm or extensive discussion, but a simple scientific statement would be appropriate. For instance it would be possible to say that the website says that more than 20% non-response rules out a study but that the data base has included two studies that don’t meet the criteria and give the chapter and verse citations.

Here’s the USDA website

http://www.ocio.usda.gov/policy-directives-records-forms/information-quality-activities/agency-quality-officials

As an addendum, anything you would send them would have to be narrow and to only apply to something that is the government’s own statement. For instance, you might think Frank Hu was wrong in what he said, but it’s not the government saying it.

Until it comes out in the 2015 DGA. Then what FH said will be wrong.

What I am trying to convey is that you can complain to USDA about the details of the NEL on this topic and they are required to respond and to make changes if what you say is correct. Again, not on ‘opinion’ but on facts about what studies they should have excluded according to their own criteria but didn’t.

Absolutely. One of the few mandates surrounding the DGA is that they must be “based on the preponderance of the scientific and medical knowledge which is current at the time.” I’m just saying that now anyone reading this blog (all 6 of you folks) has enough information to lodge the same complaint. Go for it 🙂

What? Me, sarcastic? Never. 🙂

I’d love for folks to take you up on this. Use the information in this post–or find some other anomalies of your own, they are out there in the NEL–and contact the USDA.

All I can say is that I read what you wrote, but I haven’t read all the studies that you refer to to verify that what you are saying about the studies is accurate. Someone, such as you yourself, or someone else who has actually been able to delve into this and check what you say, could contact the USDA. It’s not a complicated thing to contact them and it doesn’t have to be some kind of tome. Just something like the criteria say x but you are including two studies that don’t meet the criteria so this needs to be corrected.

It’s quite concerning that the USDA dietary guidelines (just like the Australian ones) tend not to use RCTs as their evidence base and instead rely on observational studies like those in Jacobson et al.

There are a number of RCTs (mainly in the 60s and 70s) that aimed to investigate whether replacing SFA with PUFA would reduce CHD. Unfortunately those trials were often poorly controlled, such that the high PUFA group was often advised to eat less TFA and more fruit and vegetables, omega 3s, etc. Consequently, in some of the trials the high PUFA group did better, and if you pool the trials together in a meta-analysis, particularly in a biased way like Mozaffarian et al, you can come to the conclusion that replacing SFA with PUFA reduces CHD. However, in the RCTs that were better controlled*, but not perfect (IMO), there was either no difference or increase in CHD and total mortality in the high PUFA group.

One of the mistakes made in meta-analyses is that the authors think they’re comparing apples with apples and don’t closely look at the individual RCTs they’re including. Or if they do, then they’re simply ignoring the differences and confounding variables (which if you look at Hooper et al and Ramsden et al they kind of do)

*Rose Corn Oil Trial, Medical Research Council Trial, Sydney Diet Heart Study and Minnesota Coronary Survey

One of the very few things that nearly everyone working on this issue agrees upon is that the science we have now is simply not up to the task of providing the sort of detailed micro-managing of diet that the DGA does. (But does that stop the DGA????)

I’m not really sure why meta-analyses are even allowed as evidence in these situations. If they want to look at the RCTs involved they can just look at them. And if it is a meta of observational data, then we’re usually talking about comparing apples and orangutans.

So that’s why Jackobsen is such a touchstone. However, looking at what happens when PUFA and SFA are exchanged begs the question – if PUFA has benefits for some people, which is at least plausible if that PUFA includes some extra n-3, is it necessary to lower SFA to see these? That part is less plausible, and lowering SFA monotonically seems to do nothing.

Anyway, I came across a massive and usually unmeasured, and I’m pretty sure always uncontrolled for, confounder the other day – parity. Number of kids a woman gives birth too.

High parity is strongly associated with CVD, with various increases for preterm and complications of birth.

This gets interesting because, naturally, parity and diet are closely related, with vegans having lowest parity, meat eaters highest.

The – huge – difference is clearly seen in table 1 from this paper http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4144109/

The more kids you have, the less money you have. The more jobs you and your husband need to work, the less choice you have in where you work, the less adult education you have time for, and so on.

Fascinating. Thanks for sharing this. I can use this 🙂

Awesome post!

I was in the dietetics program at Arizona state University for the last few years and in one of my classes we had an assignment to evaluate a question asked in the NEL database. I thought, ‘wow here is going to be some contrary evidence to my thinking of saturated fat and heart disease”. Well, to my surprise, I found the same stuff you did. No hard evidence was found.

If you want a to laugh a but, I recommend going through Chung et al, in this study, the saturated fat used for this study was Breyers vanilla ice cream. Yeah…

I almost went crazy in that program, sadly this is the kind of shit they are teaching to the people who will be the health professionals of tomorrow.

I had a similar experience. I had an assignment to examine the evidence in the EAL (the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics version of the NEL); my question was on low-fat diets. I expected to find (at least) some straightforward evidence that showed some significant benefits from following this diet. Yes, we have no evidence here either. I was sort of shocked. I remember thinking at the time, if this is the quality/quantity of science needed for a diet to be recommended, low-carb diet science can certainly meet that standard. Yes. But. It’s not about the science, right?

Not surprised by this at all. If you ask diabetic patients, like the ones I see, about fat, they still think it is worse for you than sugar. As I treat their wounds….sad. If only…

It is sad. When I get demoralized and I want to quit and go home and spend my days playing canasta, I think about my dad (who was diagnosed with pre-diabetes a number of years ago) and all the patients that I saw in wound clinic while I was doing my hospital rotation. Because my dad got different dietary advice than those patients, his toes have not turned black and fallen off. Gangrene and infection have not proceeded up his leg so that he would have to have a foot, then a lower limb, amputated. Instead of spending his days in a dialysis clinic or a wheelchair (or both), he travels across the state, cheering on his grandchildren at any and every endeavor that they decide to take up. It is just not right that those patients I saw in wound clinic were not even given the option of a different way. All those soccer games & middle school band concerts missed. So, canasta has to wait.

Are people incapable of doing a little science history research?

Here’s 39 papers over the last century showing the opposite:

–> http://highsteaks.com/science-diabetes-vs-low-carb-keto-diets/

If I had any life threatening malady I know that popular opinion is the LAST thing I’d be putting any faith in…

You have a critical & curious approach to life in general, maybe? Not everyone does. Lots of folks were brought up to actually trust authority and popular opinion (hence the popularity of Dr. Oz). But they’re not stupid. When I was doing my hospital internship and I had to counsel people with diabetes using materials created by pharmaceutical companies, I would simply point out to them that the material was created by the pharma company that manufactured the insulin that they would be using. And then I would say, “And if you really think they are trying to get you to use less insulin by following these dietary recommendations, well, okay.” And they got it.

Adele:

Great post! Way to go. Question: what about omitted evidence? What about the big meta-analyses e.g. Siri-Tarino 2009, or Chowdhury 2014 (http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=1846638), or, you know, all the things we cite in *this* article: http://www.ketotic.org/2013/09/the-ketogenic-diet-reverses-indicators.html which seem to fairly compellingly indicate that high carb is dangerous for your heart and high fat is not?

I guess my question is: from your knowledge of the USDA/HHS process and the NEL data set, were would we look to find out how far those bits of evidence made it through the process? Do they appear in the 2015 Guidelines (draft)? Did they get omitted from NEL entirely? Or somewhere in between those two milestones, and if they were omitted, is there documentation of why?

Thanks!

Zooko

Here’s a link to the Siri-Tarino meta-analysis that I meant: http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/91/3/535.long

The Siri-Tarino paper was a little late in coming for the 2010 DGAC report (it was published in Jan 2010, while lit searches for that report were conducted before that time).

The process for the 2015 DGAC report is different & I’m not quite sure how it will end up being represented in the NEL itself. The USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Programs created a “A Series of Systematic Reviews on the Relationship Between Dietary Patterns and Health Outcomes” which the DGAC is relying on heavily to “answer” their research questions. Here’s something fun to do: search the document for Christopher Gardner’s 2007 A-Z study. Hmmm. Where is it? Shouldn’t it have shown up somewhere, if only to be excluded?

And speaking of exclusions, notice that another large RCT on diet, Shai 2008, gets excluded: because it didn’t use a “diet index” and because calories in one arm of the study were set at 1500 and 1800 for women and men respectively (while the CNPP, in their infinite arbitrariness, set their caloric cut-off at 1600 and 2000). Another hmmm.

You’ll also notice that few (if any) studies that specifically addressed weight loss and low-carb diets were included. Why? They didn’t even bother to ask that question. And if you don’t ask the question, well, you can be assured of never having to face down the answer.

Dear Adele:

Thanks for the information.

Do you think you could up the ante somehow, from your (excellent) blogging? Like, I don’t know how this stuff is done exactly — letters to the editor? Official letters of objection sent to the perpetrators’ bosses?

I’d like to encourage and support that sort of thing, not merely to punish the guilty, but because it really might help a lot of people avoid unnecessary death and disease in the coming 5 or 10 years.

I guess such a public condemnation could go well with the sort of research project that you propose: listing important publications of relevant evidence and then finding out what happened to those publications in this process, and tabulating the results.

Regards,

Zooko

Well, I’m working my ass off (whoops, okay, it’s still there) in a PhD program that I think will allow me to take this issue to a much broader audience. And there are many others besides me hard a work on this. To the best of my ability, I assist them in any way that I can, and some other folks are, I think, getting some of this information in front of the right people. There is no doubt in my mind that nutrition science is in a state of crisis right now, the kind of crisis that precedes the kind of “revolution” that Thomas Kuhn talks about. The paradigm, it is shifting 🙂

But, yeah, if someone (who isn’t me) could go through and poke some holes in that “systematic review” and make those results public, those type of things can really make a difference. There are people in places of influence who are paying attention.

Brilliant!

I wonder if I could use your post as the basis for an infographic.

Infographic away. I’d love to see what you come up with.

Funny/sad that this almost exactly reflects a review of the AHA’s rationalisation of their guidelines… back in 1984.

–> http://highsteaks.com/a-critical-look-at-the-american-heart-associations-dietary-guidelines-from-1982/

TL;DR – The AHA:

– completely misinterpreted a bunch of science,

– used studies that were way out of date with better data easily available,

– made some stuff up without explaining reasoning,

– said that the science thus far doesn’t really stack up to see a real correlation of anything,

– concluded you shouldn’t eat fat or cholesterol anyway, because… science.

That last part is what hurts my heart the most. I get that science is a socially constructed activity & not a capture of absolutes. But when you can’t even follow your own inclusion/exclusion rules???? Geez.

There are simply no words. As Tom Naughton would say,

BANG

HEAD

ON

DESK.

OK, I found a few words. It’s simply mind-boggling to me that people are so entrenched in the low-fat dogma. Were we so naïve back in the 1970s and 1980s that we just accepted all this with no question? Apparently we were. That was a complete reversal of what people believed (and knew) at the time, and yet it seemed like overnight people accepted the new messiah-age (get it? “message” … ok, it’s a reach!). But really, it’s become a religion to some people. I thought that after the recent Time magazine article, people as a whole would at least start questioning.

So why is it so hard for people now to even CONSIDER that there might be a better way?

Great questions. I hope to make the “why did we accept this w/o question back in the 1970s/1980s?” central to my dissertation. But I’m not sure I can explain why the resistance to change–particularly on this issue–is so entrenched.

The answer to the question on entrenched resistance to change is to be found in the pages of the excellent “Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me)” by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson.

http://www.amazon.com/Mistakes-Were-Made-But-Not/dp/0156033909

I just ran across this book earlier this week (I’m teaching a course in argumentation & advocacy this fall). Looks interesting. Thomas Kuhn has some clues too, at least with regard to resistance in the scientific community. These should provide some insight into the resistance to change, but I’m still quite puzzled about the widespread enthusiastic uptake in the first place.