If you have tried carbohydrate reduction and it didn’t work for you, or you didn’t like, or you don’t agree with it in principle, you might just want to skip this. This information is provided for people who are curious about the possible health benefits of carbohydrate reduction, or for those who have tried it, liked it, and want to share some information about it with friends. I provide it here primarily because our current public health nutrition policy fails to offer this as an alternative approach to dietary health. It’s not a “magic bullet,” but another way to think about nutrition.

I welcome corrections and suggestions from anyone who has them for me, but I am not interested in arguing the merits or drawbacks of this approach to health. I’m sure if you look around, you’ll find someone else who is.

What is carbohydrate anyway?

There are three classes of molecules or “macronutrients” in food—protein, fat, carbohydrate—and all three have two basic functions in the body.

- To provide energy in the form of calories

- To build and maintain structures and/or regulate processes in the body

The primary role that carbohydrate foods play in our diet is to provide energy. However, carbohydrate also plays a very important role in how we store energy from the food we eat. Simply put, if you eat more food than your body needs for immediate energy use, the carbohydrate signal in some foodswill tell the body to store the extra energy, mostly as fat. If you eat few carbohydrate foods to begin with, your body is less likely to store fat because that signaling process isn’t triggered. Foods with a lot of carbohydrate are usually plant-based items like pasta, cereal, breads, fruits, and starchy vegetables because sugars and starches are how plants store energy. Animal-based foods naturally have less carbohydrate content because animals store most of their energy as fat. Because our taste buds find fat and carbohydrate to be an attractive pairing, foods with fat are frequently also high in carbohydrate. For instance, we think of French fries as being “fatty,” but more of the calories in French fries come from carbohydrate than fat.

How does eating high-carbohydrate foods affect my health?

All dietary carbohydrates, even whole grains, raise blood sugar levels; the end product of all digestible carbohydrate food is a simple sugar, namely glucose. Elevated blood sugar (glucose) causes the pancreas to produce insulin. For many people, eating carbohydrate foods can cause an excessive insulin response. Insulin levels can go up more and remain elevated longer than normal. Eventually, the cells become resistant to the insulin signal.

Insulin tells your body to store fat. More importantly, it also prevents your body from burning fat that is already stored. When insulin is constantly elevated, because of a metabolic disorder or because of chronic ingestion of nutritionally-empty dietary carbohydrate, the body has many opportunities to store fat and block fat from being used as energy. This metabolic situation prevents weight loss, promotes weight gain, and contributes to fatigue and low energy levels.

What is a reduced-carbohydrate diet?

The current national standard for recommended daily intake for carbohydrates is 130 grams/day. Anything below that can be considered a reduced-carbohydrate diet, although Americans typically eat two to three times that amount in a day [1]. The benefits of carbohydrate reduction seem to be continuous; as carbohydrates are reduced, health benefits usually increase. However, for those addressing health concerns such as diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and abnormal lipids, there is usually a threshold effect. In other words, dietary carbohydrates don’t have to be eliminated, just lowered to the point that an individual is able to achieve his or her health goals.

For some people, there is a maximum benefit at very low carbohydrate levels, which is why early phases of popular reduced-carbohydrate diets target very low carbohydrate levels [2]; however, some people may achieve similar benefits at higher levels of dietary carbohydrate. Reduced-carbohydrate diets do not necessarily require higher fat or protein intakes; in many cases, little protein or fat is added back in for the carbohydrate that is removed [3].

Most reduced-carbohydrate diets aim for a level of less than 60 grams of carbohydrates, as that is the level at which the body begins to rely on fat and ketones for fuel instead of carbohydrates (this is called being “in ketosis”). A very low-carbohydrate diet will keep carbohydrate intake at around 20 to 30 grams/day. At this level, almost everyone will be successful in regulating blood sugar and lowering insulin levels and losing weight. It is important to note that many people who are not overweight or do not have any other metabolic conditions or chronic illnesses can also benefit from reducing the carbohydrate in their diet. This type of “reduced carbohydrate diet” would contain up to 45% of calories from carbohydrate, still considerably less than the 50 to 65% that the USDA Dietary Guidelines recommend.

Definitions [4]:

Moderate carbohydrate diet: Over 130 grams carbohydrate per day, up to 45% of total calories.

Reduced-carbohydrate diet: Contains 30 to 130 grams of carbohydrate per day; may or may not induce ketosis.

Low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diet: Contains less than 30 grams of carbohydrate per day; will usually permit ketosis to occur.

What is ketosis and how does it affect my body?

Ketosis occurs when your body switches from burning carbohydrates to burning fat for fuel. It can occur during any period of reduced energy intake, such as an overnight fast or during any weight loss program. One of the by-products of the fat-burning process is ketones, which your body uses for fuel. Ketosis is not harmful, and in fact may have some benefits, such as improved weight loss, suppressed appetite, and increased energy levels. As long as protein intake is sufficient, concerns that ketosis causes muscle loss, “starves” the brain, or otherwise damages your health are unfounded. You can measure your ketone levels with test strips from the drugstore if you are interested.

Ketosis should not be confused with ketoacidosis, a situation where ketones are present in the blood when blood sugar levels are elevated. This can happen in unusual conditions, such as with poorly-controlled type 1 diabetes or with excessive alcohol consumption in conjunction with type 2 diabetes.

How can reducing dietary carbohydrate improve my health?

Weight loss

Most people are familiar with reduced-carbohydrate diets through popular weight loss books. In fact, reduced-carbohydrate diets, when used appropriately, have consistently been shown to be more effective for weight loss when compared to other types of diets [5, 6, 7]. People who have had difficulty losing weight in the past can often find success with a reduced-carbohydrate diet, as this type of diet specifically addresses the metabolic conditions that lead to weight gain in the first place. For weight loss purposes, reduced-carbohydrate or low-carbohydrate diets seem to be more effective than a moderate carbohydrate diet; in reduced-carbohydrate weight loss studies, weight loss slows and weight is regained with the re-introduction of carbohydrates into the diet [6].

This does not mean that “calories don’t count” on a reduced-carbohydrate diet. When insulin levels remain low, there is no efficient storage mechanism for extra calories. At the same time, consuming more energy than is needed will prevent the body from using its body fat stores for energy requirements. Reducing nutritionally-empty carbohydrates will reduce both calories and carbohydrates and may provide health benefits that go beyond weight loss.

Beyond weight loss

Weight is not the only thing that can improve when excess carbohydrates are reduced in the diet. Many people report increased energy and reduced hunger on a low or reduced-carbohydrate diet. During comparative diet studies, those who are placed on a reduced-carbohydrate diet typically consume fewer calories than other dieters despite the fact that caloric intake is not restricted on a reduced-carbohydrate diet [6, 7, 8, 9]. Proper nutrition that provides adequate protein and fat, stabilizes blood sugar, and reduces insulin levels can contribute to a general feeling of improved well-being when dietary carbohydrate is reduced.

Reducing dietary carbohydrates stabilizes blood sugar and reduces insulin output

Reducing carbohydrates can stabilize blood sugar levels and prevent the excessive output of insulin [10, 11, 12]. Stabilizing blood sugar and insulin levels by reducing carbohydrate intake can help address health concerns such as cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, and overweight and obesity. Protein causes only a small rise in blood sugar; fat does not cause any rise in blood sugar at all. Because protein and fat have a minor impact on blood sugar levels, they do not cause the body to produce excessive amounts of insulin.

Insulin becomes elevated as a direct response to dietary carbohydrate. The elevated insulin levels that accompany a high-carbohydrate diet could contribute to the development of diseases such as heart disease and Type 2 diabetes. Elevated insulin levels are an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes and are one of the indicators of Metabolic Syndrome. [13, 14, ]. Insulin levels become elevated long before abnormal blood sugar readings are detected [15]. Chronically increased output of insulin from the pancreas can lead to pancreatic “burn out,” when no more or very little insulin is produced and blood sugar levels are poorly controlled [15, 16]. At this point, a person is frequently diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. Controlling carbohydrate intake will reduce insulin production and restore the body’s ability to burn stored body fat for energy.

Reducing dietary carbohydrate changes your lipid profile for the better

Reduction on dietary carbohydrate reliably lowers triglyceride levels and raises HDL (the “good” cholesterol). In many cases, a reduced-carbohydrate diet will also change the quality of LDL particles, increasing the ratio of large (will not “clog” the arteries) LDL to small (can “clog” the arteries) LDL. Both changes in the lipid profile represent a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease. [2, 17, 18, 19].

A reduced-carbohydrate diet provides the most appropriate nutrition for the body

In addition, a reduced-carbohydrate diet closely follows the body’s own requirements for appropriate nutrition. High quality protein, a crucial macronutrient, is supplied in sufficient quantities. Essential fatty acids obtained from the diet would also be a typical part of reduced-carbohydrate diet (although for those who do not care for fish, a supplement may be advisable). Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K are acquired and metabolized much more effectively with a diet that encourages sufficient fat and protein consumption.

Adequate consumption of essential nutrients in protein and fat, plus reduction of unnecessary dietary carbohydrates, can have a positive aspect on many areas of health.

What chronic health conditions are improved by reducing dietary carbohydrate?

Reducing carbohydrates: weight loss and more

Reduced-carbohydrate diets have been studied primarily for their effectiveness in weight loss. In fact, research has shown reduced-carbohydrate diets to be effective for that purpose, although weight loss can be accomplished through many different approaches and may require an array of interventions, from diet to cognitive and behavioral modification. However, if weight gain or inability to lose weight is associated with a specific metabolic profile, such as Type 2 diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, or related conditions, the unique features of a reduced-carbohydrate diet can promote weight loss while correcting the underlying issues affecting overall health.

Blood sugar control, insulin resistance, and Type 2 diabetes

A reduced-carbohydrate diet is an especially effective way of improving health for those with blood sugar control issues or insulin resistance. Patients who have insulin resistance, Metabolic Syndrome, pre-diabetic conditions, or full-blown type 2 diabetes can all benefit from this treatment method. Since type 2 diabetes is a disease whose hallmark is high blood sugar levels, the key to controlling diabetes is maintaining blood sugar at normal levels. Type 2 diabetes is listed in a widely-used physician handbook (the Merck Manual) as a disorder of carbohydrate metabolism. Therefore it makes sense to treat type 2 diabetes by limiting unnecessary carbohydrate intake, just as you would treat any food allergy or sensitivity.

A person who is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes is likely to be given medication to reduce blood sugar levels. However, recent research has shown that even with drug therapy to control blood sugar levels, risk of diabetic complications and death are not significantly reduced, only delayed in onset. [20].

Medications such as insulin and other blood sugar-lowering medications cannot be synchronized as closely with the body’s needs as the body’s own processes. Common side effects of these medications are hunger, weight gain, and excessively low blood sugar levels [21]. Blood sugar levels controlled by medication may stay elevated longer than they should, leading to nerve and kidney damage. In fact, in a recent research study that was halted early, attempts to control blood sugars tightly with medication led to increased adverse effects and death; other large trials show that intensive drug therapy does not reduce overall mortality or complications of diabetes related to heart disease. [21].

Controlling blood sugars by eliminated unnecessary dietary carbohydrate is a more natural and effective way of avoiding the complications of type 2 diabetes.

Heart disease

Because controlling carbohydrate intake and insulin levels also controls how fat is stored in the body, a reduced-carbohydrate diet can be effective in addressing abnormal lipid profiles, such as those seen with Metabolic Syndrome [8, 22, 23]. One of the markers of Metabolic Syndrome is elevated triglycerides and reduced HDL levels. Reduced-carbohydrate diets have consistently been shown to reverse this lipid profile and reduce triglycerides while increasing HDL [22]. While there is an occasional rise in LDL levels on a reduced-carbohydrate diet, this is often a result of a temporary rise in blood lipids during weight loss or a result of the formula used to calculate LDL. LDL is seldom measured directly, and, mathematically, lower triglycerides levels result in higher LDL. It is also important to note that, in older adults, lower, rather than higher levels of serum cholesterol, may be associated with increased risk of CVD mortality [24, 25].

There is an increasing interest in the connection between oral bacteria and heart disease [26, 27]. Scientists have found that poor oral hygiene is associated with increased inflammation and thickening of the arterial walls. It has been well-established that the bacteria in our mouths flourish in the presence of dietary carbohydrates. Reducing dietary carbohydrate may have additional benefits beyond reducing dental caries; in fact, it may be a contributing factor in reducing heart disease.

Reducing carbohydrate intake can also lead to reductions in hypertension, considered to be a risk factor for heart disease. Although the mechanism by which this takes place is not fully understood, weight loss with a reduced-carbohydrate diet has been shown to have greater effects on reducing blood pressure than weight loss alone [28, 29].

Gluten and lactose intolerance

We are only now beginning to take into account the prevalence of intolerance to gluten (a wheat protein) and lactose (a type of sugar) intolerance in the American population. Many symptoms of these two conditions are vague, non-specific, and may be generally attributed to environmental factors and remain undiagnosed indefinitely. As a reduction in gluten and lactose naturally accompanies a reduced-carbohydrate diet, some people may experience a relief from gastrointestinal and allergic symptoms that they have been suffering from for years. Of course, a clinical diagnosis of gluten and/or lactose intolerance is easily addressed through a reduced-carbohydrate type of diet. Because some forms of schizophrenia have been associated with gluten intolerance and some patients with schizophrenia have shown improvement on a reduced-carbohydrate diet, reduced-carbohydrate diet therapy may be considered in conjunction with other medications used to treat that condition [30].

Other conditions that respond to a reduction in dietary carbohydrates

Other conditions that have been shown through clinical trials to respond to a reduced-carbohydrate diet are gastroesophogeal reflux disorder (GERD) [31, 32] and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [33]. Both of these conditions improve due to the unique features of a reduced-carbohydrate diet.

Calorie-restriction through carbohydrate restriction: the key to a long and healthy life

The only scientifically-supported method for increasing longevity that has been studied is calorie-restriction, proven to be effective in mice, dogs, and monkey [34]. Animals on calorie-restricted diets not only live longer, they live healthier lives, demonstrating a reduction in age-related diseases, including cancer. While much research remains to be done in this field, scientists have found a common feature in all animals displaying increased lifespan: insulin sensitivity [35, 36]. Calorie-reduction and increased sensitivity are also the primary features of a reduced-carbohydrate diet as well. Reducing dietary carbohydrate effectively lowers the body’s insulin output, helping the body to maintain insulin sensitivity. At the same time, reducing carbohydrate can also help lower overall calorie consumption.

Studies that have investigated the effectiveness of reducing or eliminated carbohydrate as a weight loss technique have frequently found that reduced-carbohydrate dieters limit calories despite a slight increase in fat intake—all on their own! Even though these dieters are allowed to eat an unrestricted amount of certain foods, they usually eat fewer calories than their counter-parts in the calorie-restricted groups being studied. Scientists know that dietary protein and fat, the primary components of a reduced-carbohydrate diet, are also powerful appetite suppressants. In addition, the blood sugar control and appetite regulation afforded by a reduced-carbohydrate diet may reduce the desire for between-meal snacking and the opportunities it presents for over-consumption of calories. Stable blood sugars and increased awareness of the body’s signals for true hunger and fullness may help regulate intake without the need for restrictive eating behaviors.

Why don’t all experts recommend reducing dietary carbohydrates?

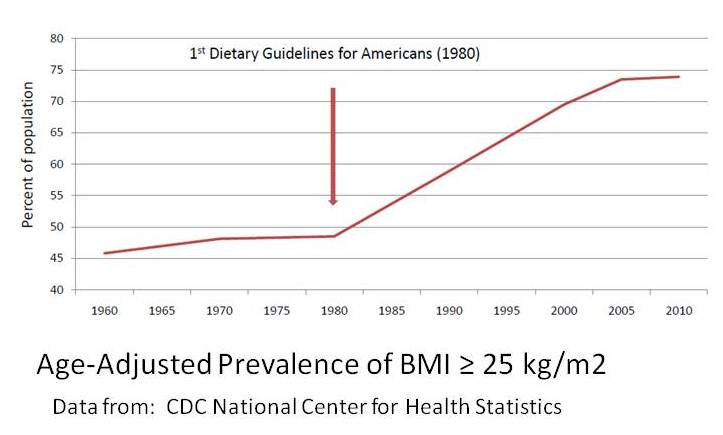

Although we like to think that science and health are fields exempt from political motivations and influences, unfortunately this is not the case. The case for a reduced-fat, high-carbohydrate diet was promoted by a few influential researchers over thirty years ago with little data to support it [3]. The US government created guidelines that followed these recommendations and many doctors have passed this advice along to their patients. However, this type of diet has never been shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of heart disease, diabetes, or overweight and obesity in our population; the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans states that its recommendations “have not been specifically tested for health benefits [37].”

Scientists have been questioning the benefits of our national dietary recommendations since they were first created in 1980. This concern has not abated in thirty years. In 2000, scientists who review the evidence for creating the Dietary Guidelines for Americans questioned the effect that low-fat diet recommendations have had on the health of Americans, noting that “an increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States has corresponded roughly with an absolute increase in carbohydrate consumption” and that “Consumption of high-carbohydrate diets also can produce an enhanced [post-meal] response in glucose and insulin concentrations . . . [which] could predispose to type 2 diabetes mellitus” [38]. Many scientists have pointed to evidence that, in some cases, a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet may actually increase the risk of chronic disease. In her review of recent scientific evidence, Dr. Janet King, Chairwoman of the 2005 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, cited specifically that “evidence has begun to accumulate suggesting that a lower intake of carbohydrate may be better for cardiovascular health” [39]. A report by the Institute of Medicine’s Food and Nutrition Board issued in 2005 indicates that “Compared to higher fat diets, low fat, high carbohydrate diets may modify the metabolic profile in ways that are considered to be unfavorable with respect to chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease (CHD) and diabetes” [40]. According to Dr. Frank Hu, Professor of Nutrition and Epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, “The country’s big low-fat message backfired. The overemphasis on reducing fat caused the consumption of carbohydrates and sugar in our diets to soar. That shift may be linked to the biggest health problems in America today” [41].

Nevertheless, the United States Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services have continued to create dietary recommendations that insist that “Healthy diets are high in carbohydrates” [42]. These two powerful governmental agencies are charged with protecting the health of Americans while, at the same time, promoting the interests of the American food and drug industries. These two responsibilities may often be in direct conflict, and frequently it is the American consumer that loses.

The top three agricultural products in America are wheat, corn, and soy, the primary ingredients in high-carbohydrate, nutritionally-empty processed foods, from cereal to frozen entrees to fast foods [43]. These foods can be very appealing to consumers despite their lack of nutritional content. A diet based on these foods may result in chronic illnesses for which a prescription drug is a more convenient remedy than a change in diet and lifestyle. Unfortunately, what is bad for the consumer is good for the food and drug industries. There is little incentive from either the government or from industry to assist the consumer in making better choices.

Some concerns about reduced-carbohydrate diets

Although mankind subsisted for thousands of years on diets relatively low in the grains and cereals that now make up a large portion of the calories that Americans consume, many misunderstandings and myths surround this approach to healthy eating. According to the Institute of Medicine, “The lower limit of dietary carbohydrate compatible with life is apparently zero” [40]. No nutritional deficiencies or metabolic disorders are associated with limited carbohydrate intake as long as protein and essential fats are consumed in enough quantities to provide sufficient energy.

Myth: The large quantities of protein consumed on a reduced-carbohydrate diet can cause osteoporosis, kidney damage, and heart disease.

This is a persistent myth that is wrong on two counts. First of all, a reduced-carbohydrate diet does not mean a high-protein diet! Studies comparing low-fat and reduced-carbohydrate diets demonstrate only a slight increase in protein consumption for reduced-carbohydrate dieters, well within the 10 -35% of calories recommended by the Institute of Medicine, despite unlimited allowance of protein foods on the diet [2].

Protein consumption does not lead to osteoporosis. In fact, poor protein intake can contribute to bone loss [5]. There is no evidence indicating that protein intakes at the levels consumed on a reduced-carbohydrate diet lead to kidney disease [44, 45, 46, 47, 48]. In fact, low protein intake can lead to decreased renal function. Finally, protein intake is not correlated with heart disease risk. The Nurses’ Health Study actually demonstrated an inverse relationship between protein intake and risk of cardiovascular disease [40]. One of the risk factors for heart disease is obesity. Experts acknowledge that replacing dietary carbohydrate with protein improves weight loss, which in turn can reduce risk of heart disease [49].

Myth: Diets high in fat and cholesterol increase the risk of obesity, certain types of cancer, and heart disease.

Fat and cholesterol play essential roles in our metabolism. Dietary fat is necessary for the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). Fat functions in cell-signaling, gene expression, and may play a role in regulating inflammation, insulin action, and neurological function. Fat provides essential fatty acids your body can’t make on its own. Cholesterol is an important of part of every cell membrane and is a precursor to hormones such as estrogen and testosterone.

There is no direct link between total dietary fat and cardiovascular disease, obesity, and cancer [40, 50 ]. There is no conclusive data relating cholesterol intake to cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease endpoints [51, 52, 53]. The past research that seems to demonstrate negative health effects of fat consumption has been confounded by the fact that this research has been done with diets that are high in both fat and carbohydrate. We now know that dietary carbohydrate has a tremendous effect on how other nutrients are metabolized, especially dietary fat. When high-fat diets are studied without high carbohydrate, these negative health effects are not shown. In fact, research has shown that high-fat, reduced-carbohydrate diets can improve weight loss, blood sugar control, insulin resistance, and risk factors for heart disease, along with indicators of inflammation that scientists believe is its underlying cause.

The diet that is healthiest is the diet that is healthiest for you.

Choosing to reduce carbohydrate intake can be a healthy approach to a lifetime of wonderful eating, but although the body does not need extra carbohydrates added to the diet to be healthy, carbohydrates do not need to be excluded entirely. There is no one-size-fits-all diet that can guarantee good health for everyone. This information and a trusted healthcare provider can help you choose the foods that are right for you.

This information was brought to you by Healthy Nation Coalition, a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting nutritional literacy and individualized nutrition in the context of open, transparent, and sustainable food-health systems. We do not accept government or industry funding. Help us create thoughtful progress towards a healthier future. For more information, contact:

Healthy Nation Coalition

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in intake of energy and macronutrients–United States, 1971-2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004 Feb 6;53(4):80-2.

2. Hite AH, Berkowitz VG, Berkowitz K. Low-carbohydrate diet review: shifting the paradigm.Nutr Clin Pract. 2011 Jun;26(3):300-8. Review.

3. Hite AH, Feinman RD, Guzman GE, Satin M, Schoenfeld PA, Wood RJ. In the face of contradictory evidence: report of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans Committee. Nutrition. 2010 Oct;26(10):915-24.

4. Accurso A, Bernstein RK, Dahlqvist A, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction in type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008 Apr 8; 5:9.

5. Hession M, Rolland C, Kulkarni U, Wise A, Broom J. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities. Obes Rev. 2009 Jan; 10(1):36-50.

6. Gardner C, Kiazand A, Alhassan, et al. Weight Loss Study: A Randomized Trial Among Overweight Premenopausal Women: The A TO Z Diets for Change in Weight and Related Risk Factors .Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN. JAMA 2007; 297(9): 969-977

7. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight Loss with a Low-Carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or Low-Fat Diet. NEJM 2008; 359: 229-241.

8. Yancy WS Jr, Olsen MK, Guyton JR, Bakst RP, Westman EC. A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004 May 18; 140(10):769-77.

9. Brehm BJ, Seeley RJ, Daniels SR, D’Alessio DA. A randomized trial comparing a very low carbohydrate diet and a calorie-restricted low fat diet on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88:1617-23.

10. Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Mavropoulos JC, Marquart M, McDuffie JR. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008 Dec 19; 5:36.

11. Yancy WS, Foy M, Chalecki AM, Vernon MC, Westman EC. A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet to treat type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2005, 2:34.

12. Gannon M, Nuttall F. Effect of a High-Protein, Low-Carbohydrate Diet on Blood Glucose Control in People with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2004; 53:2375 – 2782.

13. Reaven GM. Insulin resistance: the link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008 Sep; 37(3):581-601, vii-viii.

14. Cao W, Ning J, Yang X, Liu Z. Excess exposure to insulin is the primary cause of insulin resistance and its associated atherosclerosis. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2011 Nov;4(3):154-66.

15. Kendall DM, Cuddihy RM, Bergenstal RM. Clinical application of incretin-based therapy: therapeutic potential, patient selection and clinical use. Eur J Intern Med. 2009 Jul;20 Suppl 2:S329-39. Epub 2009 Jun 24. Review.

16. Corkey BE. Banting lecture 2011: hyperinsulinemia: cause or consequence? Diabetes. 2012 Jan;61(1):4-13.

17. Menown IB, Murtagh G, Maher V, Cooney MT, Graham IM, Tomkin G. Dyslipidemia therapy update: the importance of full lipid profile assessment. Adv Ther. 2009 Jul; 26(7):711-8.

18. Rosenson RS. Biomarkers, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008 Jun; 6(5):619-22.

19. Carmena R, Duriez P, Fruchart JC. Atherogenic lipoprotein particles in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004 Jun 15; 109(23 Suppl 1):III2-7.

20. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998 Sep 12; 352(9131): 837-53

21. Skyler JS, Bergenstal R, Bonow RO, et al. Intensive glycemic control and the prevention of cardiovascular events: implications of the ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VA diabetes trials: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a scientific statement of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009 Jan 20;119(2):351-7. Epub 2008 Dec 17.

22. Volek JS, Phinney SD, Forsythe CE, Quann EE, Wood RJ, Puglisi MJ, Kraemer WJ, Bibus DM, Fernandez ML, Feinman RD. Carbohydrate restriction has a more favorable impact on the metabolic syndrome than a low fat diet. Lipids. 2009 Apr; 44(4):297-309.

23. Sharman MJ, Gómez AL, Kraemer WJ, Volek JS. Very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets affect fasting lipids and postprandial lipemia differently in overweight men. J Nutr. 2004 Apr; 134(4):880-5.

24. Anderson KM, Castelli WP, Levy D. Cholesterol and mortality. 30 years of follow-up from the Framingham study. JAMA. 1987 Apr 24;257(16):2176–80.

25. Esrey KL, Joseph L, Grover SA. Relationship between dietary intake and coronary heart disease mortality: lipid research clinics prevalence follow-up study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996 Feb;49(2):211–6.

26. Humphrey LL, Fu R, Buckley DI, Freeman M, Helfand MJ. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:2079-2086.

27. Bahekar AA, Singh S, Saha S, Molnar J, Arora R. The prevalence and incidence of coronary heart disease is significantly increased in periodontitis: A meta-analysis. Am Heart J 2007;154:830-837.

28. Yancy WS Jr, Westman EC, McDuffie JR, Grambow SC, Jeffreys AS, Bolton J, Chalecki A, Oddone EZ. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet vs orlistat plus a low-fat diet for weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Jan 25; 170(2):136-45.

29. Frisch S, Zittermann A, Berthold HK, Götting C, Kuhn J, Kleesiek K, Stehle P, Körtke H. A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of carbohydrate-reduced or fat-reduced diets in patients attending a telemedically guided weight loss program. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009 Jul 18; 8:36.

30. Kraft BD, Westman EC. Schizophrenia, gluten, and low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diets: a case report and review of the literature. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2009 Feb 26; 6:10.

31. Austin GL, Thiny MT, Westman EC, Yancy Jr. WS, Shaheen NJ. A very low carbohydrate diet improves gastroesophageal reflux and its symptoms: A pilot study. Dig Dis Sci 2006; 51:1307-1312.

32. Yancy Jr WS, Provenzale D, Westman EC. Improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease after initiation of a low-carbohydrate diet: five brief case reports. Altern Ther Health Med 2001; 7:120, 116-9.

33. Mavropoulos JC, Yancy WS, Hepburn J, Westman EC. The effects of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet on the polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2005 Dec 16; 2:35.

34. Heilbronn LK, Ravussin E. Calorie restriction and aging: review of the literature and implications for studies in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Sep;78(3):361-9. Review.

35. Bartke A. Insulin and aging. Cell Cycle. 2008 Nov 1;7(21):3338-43. Epub 2008 Nov 15. Review.

36. Facchini FS, Hua NW, Reaven GM, Stoohs RA. Hyperinsulinemia: the missing link among oxidative stress and age-related diseases? Free Radic Biol Med. 2000 Dec 15;29(12):1302-6. Review.

37. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010.

38. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2000, to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Washington, DC: 2000.

39. Lomangino K. “Dietary Guidelines 2010: What Should We Wish For?” Nutrition Insight. 2009 Jan 35(1): 4-6.

40. Report of the Panel on Macronutrients, Subcommittees on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients and Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes, and the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

41. Jameson, M. “A Reversal on Carbs.” Los Angeles Times. December 20, 2010. Accessed December 28, 2010. http://articles.latimes.com/2010/dec/20/health/la-he-carbs-20101220

42. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010. Accessed July 15, 2010. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010-DGACReport.htm

43. Imhoff, D. Foodfight: The Citizen’s Guide to a Food and Farm Bill. Healdsburg, CA: Watershed Media, 2007.

44. Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD, Noakes M, Clifton PM. Renal function following long-term weight loss in individuals with abdominal obesity on a very-low-carbohydrate diet vs high-carbohydrate diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 Apr; 110(4):633-8.

45. Pecoits-Filho R. Dietary protein intake and kidney disease in Western diet. Contrib Nephrol. 2007;155:102-12.

46. Kirby RK. Low-carbohydrate dieting. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Jun 1; 73(11):1896, 1901.

47. Eisenstein J, Roberts SB, Dallal G, Saltzman E. High-protein weight-loss diets: are they safe and do they work? A review of the experimental and epidemiologic data. Nutr Rev. 2002 Jul; 60(7 Pt 1):189-200.

48. Freedman MR, King J, Kennedy E. Popular diets: a scientific review. Obes Res. 2001 Mar; 9 Suppl 1:1S-40S.

49. Layman DK. Protein quantity and quality at levels above the RDA improves adult weight loss. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004 Dec;23(6 Suppl):631S-636S. Review.

50. Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Saturated fat, carbohydrate, and cardiovascular disease.Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Mar;91(3):502-9

51. Gordon T, Kagan A, Garcia-Palmieri M, et al. Diet and its relation to coronary heart disease and death in three populations. Circulation. 1981 Mar;63(3):500-15.

52. Jones PJH. Dietary cholesterol and the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients: a review of the Harvard Egg Study and other data. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2009 Oct;(163):1–8, 28–36.

53. Fernandez ML, Calle M. Revisiting dietary cholesterol recommendations: does the evidence support a limit of 300 mg/d? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010 Nov;12(6):377–83.

Despite what this particular link implies, carbohydrates are not essential nutrients. Yes, some people may do better with some carbohydrate in their diets; most of us like the variety. And yes, carbohydrates are “used in your brain for energy,” but your body supplies your brain with glucose and/or ketone bodies that it can make all by itself, given a diet with adequate fuel. You don’t need to eat carbs for your brain. That said, there’s no reason to restrict all or most carbs just because you don’t need them for adequate essential nutrition. Get the nutrients you need first: protein, vitamins/minerals, essential fatty acids. Carbs may (or may not) fit in as well, depending on your own personal tolerance, preferences, health goals, etc.

Check your information again excessive ketones in your urine is bad and so isn’t ketosis.

ketosis

[kitō′sis]

Etymology: Gk, keton + glykys, sweet + osis, condition

the abnormal accumulation of ketones in the body as a result of excessive breakdown of fats caused by a deficiency or inadequate use of carbohydrates. Fatty acids are metabolized instead, and the end products, ketones, begin to accumulate. This condition is seen in starvation, occasionally in pregnancy if the intake of protein and carbohydrates is inadequate, and most frequently in diabetes mellitus. It is characterized by ketonuria, loss of potassium in the urine, and a fruity odor of acetone on the breath. Untreated, ketosis may progress to ketoacidosis, coma, and death.

http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/ketosis

You use the word “excessive.” How is “excessive” determined?

Okay, so you want fat people to stop being fat, right? How are they supposed to do this? By breaking down fats and utilizing them for energy, right? Oh, wait, but not “excessively” (whatever that means). Here is an explanation from an MD:

“There are ketones in the blood in small amounts virtually all the time. They are dangerous if they reach the point in the blood stream (about 6.5 to 7.0 mM/L) where they exceed the ability of the blood buffers to neutralize them (ketoacidosis). Dietary ketosis is not considered dangerous and ketones are capable of being used as an energy source by the brain. Red blood cells and parts of the kidney do not use ketones, but gluconeogenesis is quite capable of supplying the energy source for this tissue.”

An excellent article on this topic can be found here.

Everything a numbskull will smack themselves in the head for having not read before saying really dumb things:

–> http://highsteaks.com/forum/health-nutrition-and-science/nutritional-ketosis-vs-ketoacidosis-369.0.html

Excellent information! Thanks for sharing this link.

Hi, here is some significant information which may change reader’s point of view :

Our tissues(organs) have specific abilities to use fuels (energy sources). E.g. the major source of energy for Brain and nerve cells comes from oxidation of glucose. Best source are carbohydrates. Fatty acids (fat) cannot be oxidized because of the impermeability of the blood-brain barrier (fuels are circulated in blood). During prolonged fasting and in starvation, only some of the energy can be derived from the oxidation of ketones. Hence people can experience problem with concentration and etc.

Another organ worth to mention are Red Blood Cells. They rely solely on glucose as a fuel so they can transport oxygen to all cells.

Please note that body can interconvert some fuels. However, conversion of Fat to Carbohydrate is not permitted, hence you will never get enough glucose to drive your brain and nerves.

Consider Body Glucose Reserves:

Extracellular glucose 10g

Liver glycogen 75g

Muscle glycogen 250g

Consider Basic Metabolic requirements for fuel (energy for basic physiologic functions), i.e. breathing, hearbeat etc. At rest body consumes 160-200 g glucose per day. The brain is the major consumer, using approx 120 g

The amount of glucose held in reserve by the liver can be depleted within a few hours and if the individual is not fed (carbs), the liver begins to synthesize the glucose by breaking down the protein (your muscle) to provide the carbon precursors. The Fat can not provide the carbon precursor therefore will not be broken down to replace carbs.

Thanks for consideration. xx

Ref: Metabolism, 1st ed, by C.J.Coffee PH.D.

This is from a textbook for 1st/2nd year med students (or maybe for board review); it isn’t exactly an in-depth portrait of human biochemistry.

The questions this raises are, first all, how do we know that the brain uses 120 g of glucose a day? Where does that number come from–or the numbers for any other body parts for that matter? In the Institute of Medicine’s Food & Nutrition Board’s 2005 Macronutrient Report, they go into some detail:

“The lower limit of dietary carbohydrate compatible with life apparently is zero, provided that adequate amounts of protein and fat are consumed.”

And: “The requirement for glucose has been reported to be approximately 110 to 140 g/d in adults (Cahill et al., 1968). [“Reported to be,” not “is”–these are two different things. The only reference is one study from 1968]. Nevertheless, even the brain can adapt to a carbohydrate-free, energy-sufficient diet, or to starvation, by utilizing ketoacids for part of its fuel requirements [emphasis mine]. When glucose production or availability decreases below that required for the complete energy requirements for the brain, there is a rise in ketoacid production in the liver in order to provide the brain with an alternative fuel. This has been referred to as “ketosis.” Generally, this occurs in a starving person only after glycogen stores in the liver are reduced to a low concentration and the contribution of hepatic glycogenolysis is greatly reduced or absent (Cahill et al., 1968). It is associated with approximately a 20 to 50 percent decrease in circulating glucose and insulin concentration (Carlson et al.,1994; Owen et al., 1998; Streja et al., 1977). [For people with diabetes, this would be a good thing.] These are signals for adipose cells to increase lipolysis and release nonesterified fatty acids and glycerol into the circulation. [For obese people, this would be a good thing.]”

Just because you are not eating carbohydrate, does not mean your body is somehow “deprived of” glucose. One of the most remarkable things I remember from clinic is people coming in after being on a low-carb diet for a few weeks and going on and on about how their “mental fog” had lifted and how they felt that they could concentrate and think clearly for a change. Could be that the lowered insulin production due to the restriction of carbs in their diet was actually allowing MORE glucose to get to their brains–or maybe their wacky brains just happened to prefer some ketones in the mix too.

Bottom line: It’s all well and good to refer to knowledge that we’ve constructed from various places remote from ourselves–I do it myself. But the ultimate arbiter of your body’s truth is itself, not a textbook or a PubMed article. It’s sort of goofy to say that conversion from fat to carbohydrate is “not permitted.” Are the Metabolism Police going to come along and put up little orange traffic cones along the pathways where this actually does happen? Do kids with epilepsy whose brains happen to work better with no carbohydrate in the diet get a Get Out of the Jail of Confusion Free card?

I’ve provided material on this page for people who wish to explore this way of eating because the standard approach of a high-carb/low-fat/low-calorie diet has not worked for them, or because they have noticed that the information passed along the usual chain of experts has not been particularly successful in addressing the health needs of our population, or because they’ve read the history of our current default definition of “healthy diet” and are aware that it is based more on cultural norms and a selective approach to premature, weak, and inconclusive science than “facts”–whatever those are. I don’t expect that it will be the right path for all people. But I don’t know that it is all that helpful to perpetuate unfounded and simplistic–and frankly, what seems to me to be somewhat fear-mongering–claims.

myself I am following a low carb diet (I did the atkins type last year for over 2 months, didn’t work, and I couldnt stick to it). right now I am taking in about 25percent or less total caloires as carb and only picking quality carbs. I suffer metabolic syndrome, I did the research/experimentation and it seems that this way of eating is the only way to address metabolic syndrome. by the way I want to comment on the low caloire diets of the animals? it is important to remember anytime you lower caloiric intake under maintaince, the body slows the metabolism down,cannabalishes it’s own protein stores to make gluocse, and the parameters they judge to mean healthier is not really that at all. living longer doesn’t equate with being healthier, it just means your body has slowed down. I have done the low caloires diet and it is true what they say, your parameters get better (as far as the tests results) your health deterioates dramatically passed 4 months following the diet. fatigue increases, muscle wastage is noticable, athletic performance drops dramatically, (this was a1800 caloire a day diet too some days up to 2000 when really hungry) and hunger increases and sleep quality goes down. also I am not sure if your are aware that insulin spikes do not cause health problems (hyperinsulimia that is prolonged does) and leptin is a counter act to its fat storing mode. restore insulin response and you restore leptin response, I have learned unless you lower your bodys’ fat setpoint, set by past eating and lack of eating habits you will always be fighting to stay slim.

so far this diet I have been following (close to 80% plant based low carb) has actually been very comfortable and almost easy to stay on. I am surprising myself. good article nonetheless.

I agree with much of what you are saying. In terms of calorie restriction, I think the primary benefits are that the animals are being fed, first, nutritionally adequate diets and, second, low-calorie ones. The key is that they are not feeding the animals much beyond what is nutritionally essential.

As for insulin spikes not being the problem–I wish I knew for certain that is the case. I’m afraid that we know so little about how insulin activity in any given individual can be measured and normed over time–and then related to health outcomes–that it is hard to say what is/is not “the problem.” Is one insulin spike not “a problem” or 2 or 7 or 146? Every day, a few times a week, a few times a month? Do “spikes” ever lead to “curves” that lead to prolonged hyperinsulinemia? We just don’t know for any given individual. We don’t have a consistent way of measuring insulin (fasting, insulin 30, insulin AUC, etc) and one person’s “normal” may be another person’s “problem.”

I’m glad you’ve found what works for you and that feels, most importantly to me, comfortable and easy to stay on. Stay tuned into your body . . .