In case you missed it, in a recent article published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine entitled Overstatement of Results in the Nutrition and Obesity Peer-Reviewed Literature (not making this up), the authors found that a lot of papers published in the field of obesity and nutrition have, shall we say, issues.

Well–as they say down South– I never!

Here’s how the authors described statements that would be coded as “overreaching”:

- reporting an associative relationship as causal

- making policy recommendations based on observational data that show associations only (e.g., not cause and effect)

- inappropriately generalizing to a population not represented by the sample studied

Frankly, I am totally offended. Someone needs to let these folks know that, in nutrition epidemiology, correlation actually does equal causation.

What’s more, nutrition policy recommendations are supposed to be based on observational data. Hello? Dietary Guidelines? (Seriously. You don’t expect public health nutrition people to do actual experiments now, do you? I mean, unless you are talking about our population-wide, no-control-group, 35-year experiment with low-fat diet recommendations, but that’s different.)

And we don’t mind generalizing conclusions to Everyone in the Whole Wide World based on data from a bunch of white health care professionals born before the atom bomb because, honestly, those are the only data we really care about.

Equating correlation and causation, over-generalizing observations, and then using these results as the basis of policy is the bread (whole wheat) and butter (substitute) of nutrition epidemiology of chronic disease (aka NECD – pronounced Southern-style as “nekked”). NECD has a long proud tradition of misinterpreting results this way, and dammit, nobody is going to take that away from us.

Early NECD researchers have in the past tried to tentatively misinterpret results by obliquely implying that observed nutritional patterns might perhaps have resulted in the disease under investigation. Wusses.

In 1990, Walter Willett and JoAnn Manson came along to show us how the pros do it. These mavericks were the ones who made bold inroads into the kind of overreaching conclusions that made NECD great. Their data come from an observational study of female registered nurses from 11 states in the US, born between 1921 and 1946, who were asked to remember and report what they ate 4 whole times between 1976 and 1984, plus remember and report what they weighed when they were 18 years old. From this dataset, which is clearly comprehensive, and this population, which is practically every female in the US, Willett, Manson and company naturally conclude that “obesity is a major cause of excess morbidity and mortality from coronary heart disease among women in the United States” (emphasis mine). None of this wimpy “associated with increased risk of” bullshooey, obesity CAUSES heart disease, they tell us, CAUSES IT!!!! BWHAAAHAAAAA!!!!!!!

It is on this foundation of intrepid willingness to misinterpret data that the science of NECD was built. This is why Walter Willett is the Big Kahuna at the Harvard School of Public Health. He has demonstrated the courage to misinterpret data in innovative and comprehensive ways, publishing articles throughout his career that indicate that even small increases in BMI—including BMI levels that are currently considered “normal”–cause chronic disease.

In 1999, in what is considered a landmark article in overstatement, one with which all NECD acolytes should familiarize themselves, he states unequivocally, in a review of observational data:

“Excess body fat is a cause of cardiovascular diseases, several important cancers, and numerous other medical conditions . . . “ (my emphasis). Hmmmm. Observed associations reported as causal? Ding!

The rest of that sentence reads: ” . . . and is a growing problem in many countries.” His data is once again gathered mostly from American white health care professionals born before the atom bomb. Generalization from specific populations to the rest of the world? Ding ding.

And what should we do with this conclusion, according to Willett? “Preventing weight gain and overweight among persons with healthy weights and avoiding further weight gain among those already overweight are important public health goals.” Using observed associations to make policy recommendations? Ding ding ding. In one fell swoop, Willett dexterously manages to use all three designated methods of overstatement and misinterpretation in the nutrition epidemiology NECD toolbox, demonstrating why he is considered by most researchers to be “the ‘father’ of nutrition epidemiology.” This man overstates and misinterprets in ways that the rest of us can only dream of doing.

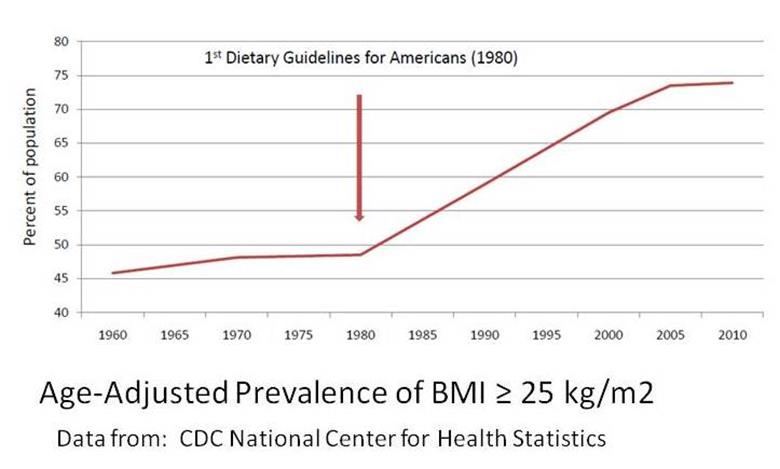

Sadly, some epidemiologist have failed to follow in Willett’s footsteps. In January 2013, Katherine Flegal, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the woman who first noted the remarkably rapid rise in obesity that began in the decade following the release of the 1977 Dietary Goals for Americans, published results that concluded that being overweight (or even mildly obese) is associated with a lower risk of death. At no point in her article does she suggest that overweight or obesity results in increased lifespan.

The response from Harvard? Walter Willett calls Flegal’s article ” a pile of rubbish” and insists that “no one should waste their time reading it” and rightly so. Why would anyone want to hear about “associations”? What kind of nonsense is that? Obviously Flegal lacks the professionalism it takes to make the leap from observation to causation.

But that’s okay. Willett and the Harvard Family know how to deal with this sort of thing.

“Someday, and that day appears to have come, I will call upon you to ignore the work of other scientists when their results contradict my own.”

Let’s face it, in the world of NECD, you can’t just have people like Flegal refusing to infer causation from observed results, just because they don’t want to. When that sort of thing happens, well, let’s just say, if she won’t do it, the Harvard Family will have to do it for her. And so they did.

In February 2013, Willett and company convened a Harvard Family gathering to, in their words, “elucidate inaccuracies in a recent high-profile JAMA article [i.e. Flegal’s] which claimed that being overweight leads to reduced mortality” (emphasis mine). Which it didn’t–except now, voila, it does. It’s not personal, Dr. Flegal. It’s strictly science.

The Family get-together was held at the Harvard School of Public Health, a “neutral convening space” that is also ground zero for the Nurses’ Health Study I and II, the Physicians Health Study I and II, and the Health Professional Follow Up Study, three datasets that have generated many NECD articles that, unlike Flegal’s article, brilliantly illustrate the powers of misinterpreting observational data. That Flegal herself was invited, but “could not attend” tells us just how ashamed she must be of her inability to make over-reaching conclusions–or perhaps she was temporarily “incapacitated” if you know what I mean.

The webcast from the meeting show us how NECD should be done, with dazzling examples of overstatement and marvelous feats of misinterpretation.

In the world of NECD, PowerPoint arrows are a scientifically-acceptable method of establishing causation.

In her shining moment, Dr. JoAnn Manson, demonstrating that she has learned well from Willett, points to the slide above and asks: “How is it possible that overweight and obesity would cause all of these life-threatening conditions, increase their incidence, and then reduce mortality?” How indeed???

The panelists highlighted the importance of maintaining clear standards of overstatement and expressed concern that Flegal’s research could undermine future attempts of more credible researchers to misinterpret data as needed to protect the health of the public.

Because that’s what it’s all about folks: protection. Someone needs to protect the science from renegades like Flegal, and someone needs to protect the public from science.

We should be thankful that we have Willett and the Harvard Family there. They know that data like Flegal’s can only confuse the poor widdle brains of Americans. Allowing us to be exposed to such “rubbish” might lead us to the risky conclusion that perhaps overweight and mild obesity won’t cause all of us to die badly, or to the even more dangerous notion that observational data should remark only upon association, not causation. And we sure don’t want that to happen.

As Don Dr. Willett says, “It is important for people to have correct information about the relationship between health and body weight.” And when he wants us to have the correct information about the relationship between health and body weight, he’ll misinterpret it for us.

Take the science, leave the cannoli.