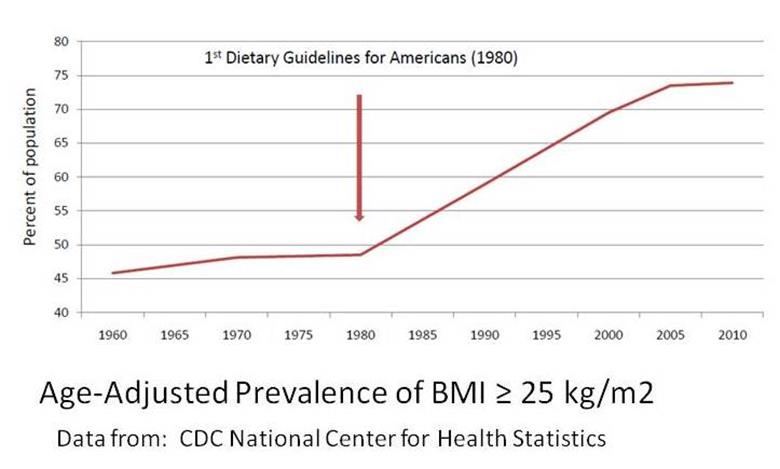

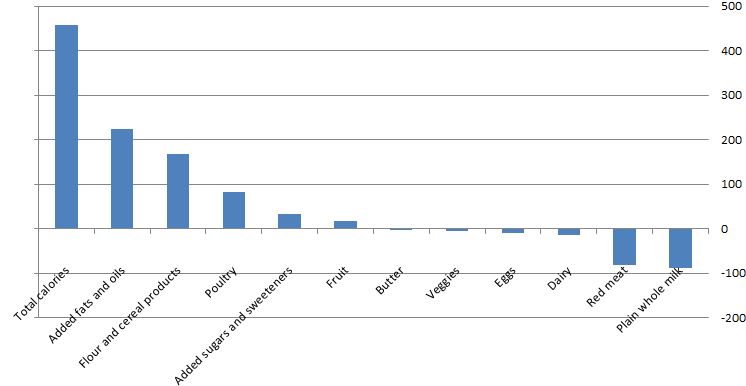

The 2015[6] Dietary Guidelines are out today. Although restrictions on cholesterol and overall fat [read: oil] content of the diet have been lifted [sorta, not really], the nutrition Needle of Progress has hardly budged, with saturated fat and sodium still lumped into the same “DANGER Will Robinson” category as trans fats and added sugars–and with cholesterol still carrying the caveat that “individuals should eat as little dietary cholesterol as possible.” The recommended “healthy eating pattern” calls for fat-free/low-fat dairy, lean meat, and plenty of whole grains, plus OIL. In other words, the diet is still low-fat and high-carb–just add vegetable oil [you know, locally sourced, whole-food canola, corn, and soy oil].

However, the most disturbing part of the Guidelines is Chapter 3, which heralds “a new paradigm in which healthy lifestyle choices at home, school, work, and in the community are easy, accessible, affordable, and normative.” In other words, let’s make what we’ve determined is the healthy choice, the easy–and morally permitted–choice for everyone [read: especially for those minority and low-income populations who insist on eating stuff we disapprove of].

Thus, it seems appropriate that today’s featured post focuses less on nutrition and more on the cultural context in which nutrition happens. Without further ado:

Low Fat, High Maintenance: How money buys lean and healthy–plus, an alternative path to both

Guest post by Jennifer Calihan at eatthebutter.org

It’s Friday evening. There is a chill in the air. The smell of ‘Walking Tacos’[i] wafts over from the row below. A rousing, “Give me an ‘S’!” commands my attention. All the cues point to one thing – I am sitting at another high school football game. I’m not really a huge football fan, but my son plays on the team, and I love watching him.

The parents and fans from my son’s school all sit on one side of the field, so the stands are filled with friends and many warm, familiar faces. I am struck, as I always am, by how good everyone looks. I see a lot of grey hair on the men but not much on the women – funny how that works! The adults watching are at least 40, and some are probably mid-fifties. But what is truly striking about this crowd is how trim they all are. Are there some people struggling with their weight? Sure. But the majority of these folks are maintaining a normal weight. No sign of the obesity epidemic on this side of the field. And I wonder what I always wonder – how do they do it – really?

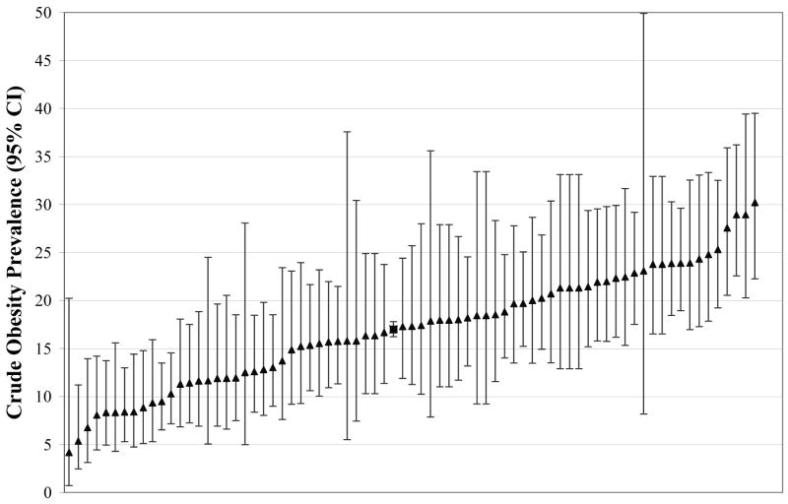

At half time, I take a walk over to the visitor side of the field to stretch my legs. Over here, the stands tell a different story. The parents and fans of the visiting team look… well, they look like most American crowds. Although this crowd seems a little younger than the home team fans, most of the people here are struggling with their weight. In fact, our national averages would predict about 68% of these adults are too heavy; 38% would be obese, plus about another 30% overweight. And, based on what I see, that sounds about right. But it is not the weight, per se, that worries me. It is the metabolic disease that often travels with excess weight that is cause for concern. Diabetes, heart disease, fatty liver… a future of pills and declining health.

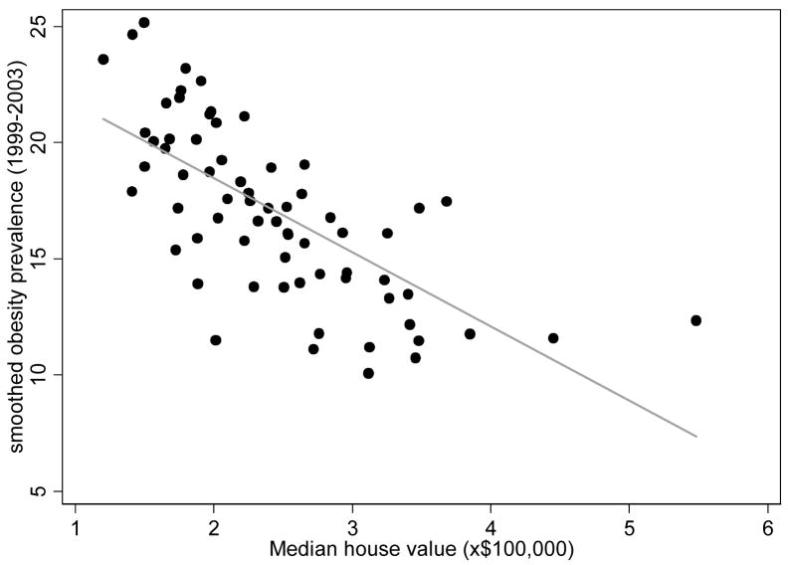

Experts acknowledge that obesity and the diseases that travel with it are tied to income. Simplistically, you might think something like, “more money = more food = more obesity,” but that is just not how it works. As most of you know, it is the reverse. “Less money = more obesity.” So it may not surprise you to hear that my son attends an independent school in an affluent area. And the visiting team is from a less affluent suburb. So, the mystery is solved – skinny rich people on one side, and overweight middle-class people on the other.

What interests me is the, ‘How?’ As in, ‘How do the skinny rich people do it?’

I affectionately refer to my neighborhood, and others like it, as ‘the bubble.’ The bubble is safe… it is comfortable… it is beautiful. But how, exactly, does the bubble protect my family and my neighbors from the obesity epidemic? Just as it is not a happy accident that actresses age amazingly well, it is not a happy accident that the affluent stay lean. Most of them spend a lot of time and money on it. They have to. Our nation’s high-maintenance dietary recommendations require most eaters to invest a great deal of resources to combat the risk of obesity and diabetes that is built into low-fat eating. Unfortunately, this means middle-income and working class families, who may be lacking the resources to perform this maintenance, are launched on a path toward overweight and diabetes. What can be done to level the playing field?

Seven Ways Money Buys Thin

1. More Money Buys Better Food

For many in the bubble, there is not a defined budget for groceries. And, let’s face it, that makes shopping successfully for healthy food – however you define it – just a tad easier. To imagine the flexibility that wealth can afford, consider this inner dialog that happens in a Whole Foods aisle near you. In the bubble, a mom might consider: “Should I buy the wild salmon or the chicken tenders for dinner? Hmmm… let’s see here. $28.50 or $8.99? My, that is quite a price difference. But those tenders are pretty processed. And they aren’t gluten-free. I’ll go with the salmon this week – Johnny loves it, and it’s so healthy.” If it doesn’t really matter if the food bill is $300 or $350 this week, why not buy the wild salmon?

Much has been written about how cheap the processed calories in products like soda and potato chips are, and how tempting those cheap calories are to people who are shopping, at least on some level, for the cheapest calorie. I find it hard to believe that any thinking mother is buying soda because it is a cheap way to feed her family. My guess is that she is buying soda for other reasons: habit, caffeine, sweet treat, etc. But certainly, refined carbohydrates and refined oils, which I believe are uniquely fattening, are cheap and convenient and are often processed into something remarkably tasty. So yes, I think small grocery budgets lead to more processed foods and more fattening choices.

Higher grocery budgets often lead to high-end grocery stores that offer exotic, ‘healthy’ products, which, on the margin, may be healthier than their conventional counterparts. Quinoa pasta, hemp seed oil mayonnaise (affectionately known as ‘hippie butter’), cereals or crackers made from ancient grains, and anything made with chia seeds all come to mind. Last week, I saw Punkin Cranberry Tortilla Chips on an endcap. Seriously? (Yet, mmmm… how inventive and seasonal!) The prices are ridiculous, but upscale shoppers snap up these small-batch, artisanal products, regardless. They may not be worth the money, and may not really taste all that good, but they carry an aura of health and make you feel really good about yourself when you put them in your cart.

Higher grocery budgets often lead to high-end grocery stores that offer exotic, ‘healthy’ products, which, on the margin, may be healthier than their conventional counterparts. Quinoa pasta, hemp seed oil mayonnaise (affectionately known as ‘hippie butter’), cereals or crackers made from ancient grains, and anything made with chia seeds all come to mind. Last week, I saw Punkin Cranberry Tortilla Chips on an endcap. Seriously? (Yet, mmmm… how inventive and seasonal!) The prices are ridiculous, but upscale shoppers snap up these small-batch, artisanal products, regardless. They may not be worth the money, and may not really taste all that good, but they carry an aura of health and make you feel really good about yourself when you put them in your cart.

The idea that money buys better food also rings true when eating out. The cheapest restaurants tend to offer more processed calories with fewer whole food choices. And, even on the same menu, the fresh, whole foods tend to be quite expensive, especially if you look at cost per calorie. Again, in the bubble, a mom might consider, “Pizza tonight? Or should we stop by Cornerstone, the local home-style restaurant, and get grilled chicken with broccoli and a salad? Hmmm… $20 or $60? Well, we did pizza last week; I think we should go to Cornerstone.”

The bottom line is that money can buy more choices and some of those choices are less likely to add pounds.

2. More Money Buys More Time to Cook and/or More Shortcuts

Most of the moms (and a rare dad or two) in my circles have time to shop and cook because they are not working full-time. Thus, higher family income can mean more home-cooked meals. Cooking at home gives families more control of ingredients and portions. It also tends to mean more whole food and less processed food, which most agree is better for weight control.

Of course, affluent working moms are the exception to this, as they have little time for grocery shopping and cooking. But, again, money can help here. Many of my friends who work full-time outsource the grocery shopping and/or cooking to a nanny, a housekeeper, or a personal chef service. Even in a mid-sized city like Pittsburgh, there are boutique, foodie storefronts that deliver healthy, home-made meals for $12-16 (each). Lately, some moms are using the on-line services (like Blue Apron, Hello Fresh, Plated, and even The Purple Carrot, which offers a vegan menu) that ship a simple recipe and the exact fresh ingredients needed to make it to a subscriber’s door each day. How convenient! For only $35 or $40, you can feed your family of four AND still get to cook dinner. Perfect. Many skip the whole experience and simply purchase fully cooked gourmet meals at high-end grocery stores, which tend to run $8-15 per person. Fabulous. What a nice option for the health-minded busy mom who is not on a budget. Of course, not all working mothers are quite so lucky.

3. More Money Buys More Time to Exercise And More Access To Exercise

I am a firm believer that one cannot exercise one’s way out of a diet full of nutritionally empty calories. BUT, if people get their diet headed in a decent direction, daily exercise can really help them cheat their way to thin even if they are still not eating right all of the time. So, exercise is certainly a factor in this puzzle, particularly for people eating low-fat diets that seem to require a steady, daily burn of calories. As a committed non-athlete, I am continually amazed by how much my friends exercise. Running, walking, biking, swimming, tennis, squash, paddle tennis – the list goes on and on. Now, small fitness facilities offer pricey, specialized workouts: lifting, yoga, Pilates, rowing, bootcamp, kick-boxing, TRX, Pure Barre, spinning, Crossfit, and the very latest – wait for it – OrangeTheory. These boutique fitness plays are becoming more common, and can run up to $500/month… not kidding. Here’s more on this trend from the WSJ.

Whew. It is exhausting to even imagine keeping up with most of my friends and neighbors. But I give it a go… sort of. Devoting an hour or more each day to exercise is much easier for those living in the bubble. Let’s be honest – people with money can afford to outsource some of the busywork of life. If you don’t like cleaning your house or mowing your lawn or weeding the flowerbeds or repainting the fence or doing laundry, don’t do it. Pay someone else to do those things, so you have time for spinning 3x a week plus Pilates (work that core) and tennis. Have baby weight to lose? No problem. Hire a babysitter and a trainer and you will make progress.

Good trainers, although expensive, often deliver more effective exercise, more efficient routines, more entertaining workouts, and better results. Appointments are scheduled and you pay whether you go or not, which makes showing up more likely. You can even find a buff guy who will yell at you if you find that motivating. Personal trainers are just one more way money buys thin.

When I think back to what my mother might have considered doing to stay fit when she was my age, I come up with one thing and one thing only: walking the golf course. And I lived up north, so the golf season was only 18 weeks long. She had no regular workout routine, nor did any of her friends. Did she have cut arms, toned abs, and look great in a bikini? Absolutely not. Was she overweight? Absolutely not. And she had the good sense not to wear a bikini, btw. It’s amazing that she could maintain her weight without regularly scheduled exercise. Her game plan was old-fashioned: bacon and eggs fried in butter for breakfast, no starch at dinner, very occasional desserts, plus a couple very dry martinis, never before 6pm. She’s a size 10 at age 91, so I’d say it worked for her.

Ti mes have changed. In the bubble, 50-year-old upper arms are proudly bared, even in winter, and women walking around in fitness gear is so commonplace that the industry has a term for this fashion trend: athleisure. If you think I might be making that up, check out this WSJ article, “Are You Going to the Gym or Do You Just Dress That Way?” The fact that Nike’s sales of women’s products topped $5 billion in 2014 is a little startling, no? Some women even need a completely separate closet to house all of their Nike apparel. Khloe Kardashian claims her fitness closet is her favorite closet. Ummm… not quite sure what to say about this, except that girl has a lot of sneakers.

mes have changed. In the bubble, 50-year-old upper arms are proudly bared, even in winter, and women walking around in fitness gear is so commonplace that the industry has a term for this fashion trend: athleisure. If you think I might be making that up, check out this WSJ article, “Are You Going to the Gym or Do You Just Dress That Way?” The fact that Nike’s sales of women’s products topped $5 billion in 2014 is a little startling, no? Some women even need a completely separate closet to house all of their Nike apparel. Khloe Kardashian claims her fitness closet is her favorite closet. Ummm… not quite sure what to say about this, except that girl has a lot of sneakers.

One doesn’t have to be athletic to exercise, so I am guilty of some of this behavior (although I swear I only have one drawer for my fitness gear). I am sure there are some naturally thin couch potatoes among the parents of the students enrolled at my son’s school, but they are the exception. Most of the lean and affluent are working pretty hard to look the way they look.

4. More Money Buys Access to Better Ideas About What Makes You Overweight

Maybe it is your personal trainer who talks to you about trying a Paleo diet. Or, perhaps your trip to Canyon Ranch exposes you to a more whole food, plant-based, healthy fats approach to eating. Or, if you prefer to ‘spa’ at Miraval, you might learn about Andrew Weil’s anti-inflammatory food pyramid. Maybe your friend recommends an appointment with a naturopathic MD who suggests that you try giving up grains. The point is, if you have money, you have a greater chance of hearing something other than ‘eat less, exercise more’ when you complain about your expanding waistline. The affluent have easy access to many different ideas about diet and health, so they can experiment with several and see which one works for them.

Today, one of the most popular alternative ways of eating is a plant-based, ultra-low-fat diet. Books and sites (like the in-your-face, aptly named Skinny Bitch brand) market snotty versions of this blueprint for weight loss to their upscale customers. I see many women in my circles eating this near vegan diet these days: lots of whole vegetables and grains, very little fat, with perhaps a little lean meat, fish or eggs occasionally. Although this is not my chosen approach, as it requires giving up too many of my favorite foods and leaves me perpetually hungry, it seems to deliver some pretty skinny results. And, since it is in vogue, it is something that will be accommodated at parties in the bubble – plenty of crudité platters with hummus and beautiful roasted beet salads, sprinkled with pumpkin seeds, pomegranate kernels, and just a touch of olive oil. In affluent communities, being among friends and acquaintances who practice an alternative approach to eating means social activities are “safe” places to eat, not minefields of temptation. I don’t mean to suggest that people in less affluent suburbs have not heard of a vegan diet or only socialize around piles of nachos; I would maintain that those communities are as invested in their health as affluent ones. But, if your social circle has access to better food, as well as better information about food, you are more likely to be a part of a “culture of skinny.”

5. More Money Buys a ‘Culture of Skinny’

Living in the bubble means living among the lean. Which, as you might imagine, increases the odds that you will be one of them. There is a lot of peer pressure to look a certain way, and being surrounded by people who look that way certainly gets your attention. It also gives you hope that being thin is a reasonable expectation – as in, “If all my neighbors have figured it out, so can I.” And, it helps that there will be healthier food at most gatherings. When the trays of cookies do come out, none of your friends will be reaching for more than one, either. So the bubble is sort of a support group for staying lean. As the success of AA can attest, when it comes to habits and willpower, support groups matter.

There is even some research to back this up. Did you know that you are 40% more likely to become obese if you have a sibling who becomes obese, but 57% more likely to become obese if you have friend who becomes obese?[ii] It’s a little weird to think of obesity as socially contagious, but it seems that social environment trumps genetics. An article in Time explains it this way: “Socializing with overweight people can change what we perceive as the norm; it raises our tolerance for obesity both in others and in ourselves.”[iii] (Emphasis mine.)

There is even some research to back this up. Did you know that you are 40% more likely to become obese if you have a sibling who becomes obese, but 57% more likely to become obese if you have friend who becomes obese?[ii] It’s a little weird to think of obesity as socially contagious, but it seems that social environment trumps genetics. An article in Time explains it this way: “Socializing with overweight people can change what we perceive as the norm; it raises our tolerance for obesity both in others and in ourselves.”[iii] (Emphasis mine.)

Living immersed in the ‘culture of skinny’ makes the sacrifices you must make to stay that way more bearable. Misery loves company, and I often think that eating way too much kale and being hungry all the time is easier if you are doing it with friends… Odd to think of widespread hunger in the affluent suburbs, I know, but I think there is a fair amount of self-imposed hunger here. Likewise, on the exercise front, you certainly won’t lack company on the paddle court or walking paths, and exercising with friends can truly be fun. Plus, you can take solace in the fact that you won’t be the only one foregoing the pleasure of lying on the couch with a glass of Chardonnay watching Downton Abby in order to make it to your spin class. In the bubble, the penalty for not keeping up with your diet and exercise regime is higher. Being the only obese mom or dad standing on the sidelines at Saturday’s soccer game can feel a bit isolating. The ‘culture of skinny’ cuts both ways – it can serve as both a carrot and a stick.

6. More Money Buys Other Ways to Treat Yourself (and the Kids)

I attended a workshop about obesity and food deserts a couple of years ago. It was sponsored by a group of venture philanthropists (think: savvy business people advising and funding fledgling non-profits), hoping to shed some light on the obesity epidemic. One of our assignments was to go into a small market in a blighted urban neighborhood and try to buy food for a few meals for a single mother and two young children. Of course, the earnest healthy eaters (self-included) in our group dominated, and we came back with things like whole milk, regular oatmeal, vegetable soup, and turkey deli meat. Boy, were we – visitors to this world – going to prove that even in a food desert and on a budget, healthy eating was possible if we made wise choices. When we returned for the debrief, another mother said, “You know, we bought all this healthy stuff, but if I were that single mother, wouldn’t I want to bring home some joy? Like, something that would make my kids smile?” And, of course, she was right. If money were tight, would I really buy unsweetened oatmeal, disappoint my kids, and listen to the subsequent really loud whining? Probably not. I think I would bring home Captain Crunch and see some joy.

In the bubble, breakfast does not have to be a treat. Like all mothers, I have to pick my battles, but breakfast can be one of mine. Would I be as likely to refuse to buy sweetened cereal if there were more important battles to fight? No. And, for the adults, maybe the food-reward cycle becomes less important when there are so many other ‘treats’ coming… the manicure, the tennis lesson, the new jeans… whatever it is that makes food less important.

7. More Money Buys Bariatric Surgery

If all else fails, people with resources have a surgical option. This is, of course, a very invasive approach to the problem – surgically altering the human anatomy to suit the modern diet rather than altering the modern diet to suit the human anatomy. But type 2 diabetes remission rates as high as 66% have been reported (two years post-op)[iv], so bariatric procedures offer more than just a cosmetic result. Our health care providers love this option. (How exciting: a new profit center!) Expensive bariatric procedures are actually available outside the bubble because insurance will cover most of the costs. How interesting that this somewhat extreme solution is the tool that is subsidized enough to bring it within reach of our middle class citizens. But, of course, those without the means to fund the deductibles, out-of-pocket costs, and time off work cannot afford even this option.

Another Inconvenient Truth

Here’s the thing. As a nation, we have (perhaps inadvertently) chosen to push, EXCLUSIVELY, a very high-maintenance diet. (And I know high-maintenance when I see it.) A diet that requires most of its eaters to either perform hours of exercise each week, or endure daily hunger, or both, in order to avoid weight gain and/or diabetes. A diet that has taken us down the tedious path of measuring portions, counting calories, and wearing Fitbits. This is far from ideal, and has left too many of us hungry, tired, crabby, and sick, not to mention pacing around our homes at night in our daily pursuit of 10,000 steps. Yes, there are those genetically gifted people who can eat low-fat, not be chained to a treadmill, and remain skinny – ignore this irrelevant minority. Yes, there are neighborhoods of affluent people where most seem to make it work – ignore them, too. We should not let the success we see in privileged communities give us hope that our current low-fat dietary paradigm is workable. The bubble is a red herring; it telegraphs false hope.

Our nation’s overall results speak for themselves. Low-fat diet advice will never work for most Americans. Never-ever. Sticking, stubbornly, to our high-maintenance food paradigm is especially harmful for our working class and middle-income citizens; people who don’t have the time, money, or resources required to make the low-fat diet work, but care just as much about their health as those in the bubble. For them, we must move on.

I am proposing that our obesity and diabetes epidemics reveal yet another inconvenient truth: our official dietary advice sets most people up for failure. Perhaps Jeb Bush could take a page out of Al Gore’s playbook and put himself on a post–campaign mission to shine a spotlight on this issue. Jeb! has access, he has public speaking skills, he has bank, and, believe it or not, he’s Paleo. Who knew?

If Jeb! were to spread the word, what solutions could he promote? What can any eater do to level the playing field a bit – to have a shot at vibrant health minus the prohibitive price tag of high-maintenance routines?

The Vintage Alternative

I run a small non-profit, Eat the Butter, that is all about real-food-more-fat eating. The main idea behind the site is that the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines have created many of our health problems, and going back to eating the way we used to eat, before they were issued, is a workable solution. The tagline is ‘Vintage Eating for Vibrant Health.’ Specifically, my site suggests some simple ideas about healthy eating. Eat real food. Unrefined. Whole food that has been around for a while. And don’t be afraid to eat more natural fat. To follow this advice, an eater must ignore some of the USDA’s guidelines.  And there are millions of Americans doing just that. (Many of these rogue eaters are affluent, by the way.) I am trying to reach out to more – to every mother. It pains me that millions of mothers are teaching their kids to eat in a low-fat way that is likely to lead, when their kids reach their 30’s or 40’s, down the path of metabolic syndrome, just as it has for us. It is time for a different approach, informed by vintage, time-tested ideas (often backed up by thoroughly modern science) about the basic components of a healthy diet.

And there are millions of Americans doing just that. (Many of these rogue eaters are affluent, by the way.) I am trying to reach out to more – to every mother. It pains me that millions of mothers are teaching their kids to eat in a low-fat way that is likely to lead, when their kids reach their 30’s or 40’s, down the path of metabolic syndrome, just as it has for us. It is time for a different approach, informed by vintage, time-tested ideas (often backed up by thoroughly modern science) about the basic components of a healthy diet.

But can vintage eating be done outside the bubble – even on a budget? It worked pretty well in the 1950’s… why not now?

Sometimes, back-to-basics can actually be pretty affordable… what could be more inexpensive and vintage than a glass of water out of the tap? Think of the groceries you would no longer need: almost all drinks – soda and Snapple and Gatorade and fruit juice (… alas, you might still ‘need’ your coffee and that glass of Chardonnay…); almost all packaged cereals and crackers and chips and snacks; almost all cookies and cereal bars and – God forbid – Pop Tarts. These products all contain highly processed ingredients and are relatively expensive for what you are getting. By buying whole, unprocessed food, the middleman is eliminated and so is his profit margin. Whole foods are usually devoid of packaging or minimally packaged, and don’t typically require an advertising budget. So there are meaningful savings here, especially if you can buy in bulk and shop the sales.

I have lingered in the bubble long enough that saving money in the grocery aisles is not exactly my expertise. My husband, much to his chagrin, can attest to this. I won’t insult you by offering second-hand tips, but there are plenty of smart women blogging about their take on buying high quality food on a budget. By mostly ignoring the packaged goods in the middle of the store, my hope is that you can offset much of the incremental spending you will do on the store’s perimeter: in the produce, dairy, and meat departments. These foods may be somewhat more expensive in general, but offer more nutrition for your food dollar and are more filling in the long run.

Can vintage eating be easy? Yes… perhaps not as easy as a drive-thru, but how long does it take to fry a pork chop? Scramble a couple of eggs? Open a can of green beans? Throw sweet potatoes in the oven? Vintage doesn’t have to be fancy. I bet you cannot drive to pick-up take-out in the time it takes to make a quick vintage meal. Simple vintage meals are the original fast food. Saturated fat is the original comfort food. If only we would give everyone permission to fry up some meat or fish and melt butter on their frozen peas. What a relief it would be for those who have very little slack in their lives and just want easy, satisfying meals that nourish them rather than fatten them.

Can vintage eating be easy? Yes… perhaps not as easy as a drive-thru, but how long does it take to fry a pork chop? Scramble a couple of eggs? Open a can of green beans? Throw sweet potatoes in the oven? Vintage doesn’t have to be fancy. I bet you cannot drive to pick-up take-out in the time it takes to make a quick vintage meal. Simple vintage meals are the original fast food. Saturated fat is the original comfort food. If only we would give everyone permission to fry up some meat or fish and melt butter on their frozen peas. What a relief it would be for those who have very little slack in their lives and just want easy, satisfying meals that nourish them rather than fatten them.

The goal, after all, is not perfection. It is to move in the general direction of whole foods… not to be confused with Whole Foods, the grocery chain, which is definitely not where you want to go if you are on a budget ;-). Give up as many modern, food science inventions as you can stomach, replace them with vintage, whole food, and I bet you will see the ‘always hungry’ status that the processed stuff drives fade. Travel towards vintage eating just as far as your time, tastes, and budget will allow. Then, see how you feel. Even if it doesn’t get you all the way to lean, it might just get you to healthy, which is really what this is about.

References

[i] ‘Walking Tacos’ are a high school snack stand special: open a snack-sized bag of Fritos and toss a couple of spoonfuls of taco meat, shredded lettuce, and grated cheese on top. Yum! Although initially put off by the idea of serving tacos in a foil bag of chips, I have made hundreds on my snack stand shifts and now marvel at the efficiency of this ingenious suburban housewife creation.

[ii] Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The Spread of Obesity in a Large Social Network over 32 Years. New England Journal of Medicine, July 26, 2007. 357-370-9.

[iii] Abedin S. The Social Side of Obesity: You are Who You Eat With. Time, September 3, 2009.

[iv] Puzziferri N. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014 Sep 3;312(9):934-42.

*******************************************************************************

Figures from the author’s comments in the comment section below: