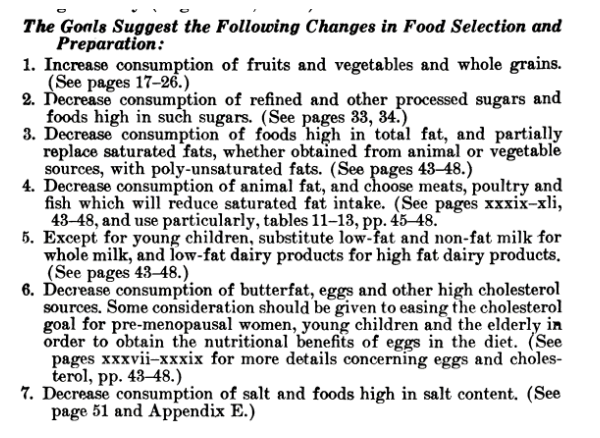

We learned that there were some significant changes in those 40 years. We saw dramatic increases in vegetable oils, grain products, and poultry—the things that the 1977 Dietary Goals and the 1980 Dietary Guidelines told us to increase. We saw decreases in red meat, eggs, butter, and full-fat milk—things that our national dietary recommendations told us to decrease. Mysteriously, what didn’t seem to increase much—or at all—were SoFAS (meaning “Solid Fats and Added Sugars”) which, as far as the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans are concerned, are the primary culprits behind our current health crisis. (“Solid Fats” are a linguistic sleight-of-hand that lumps saturated fat from natural animal sources in with processed partially-hydrogenated vegetables oils and margarines that contain transfats; SoFAS takes the trick a step further, by being not only a dreadful acronym in terms of implying that poor health is caused by sitting on our “sofas,” but by creating an umbrella term for foods that have little in common in terms of structure, biological function or nutrition.)

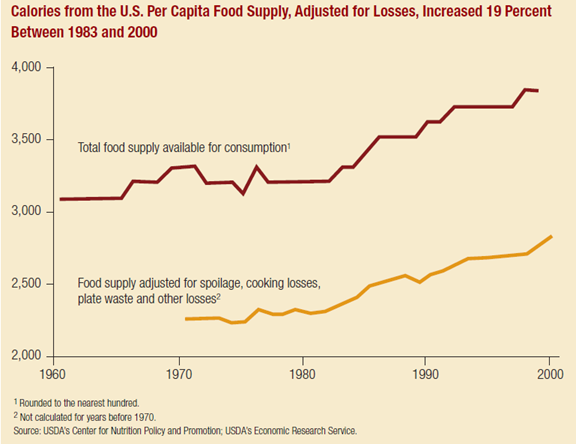

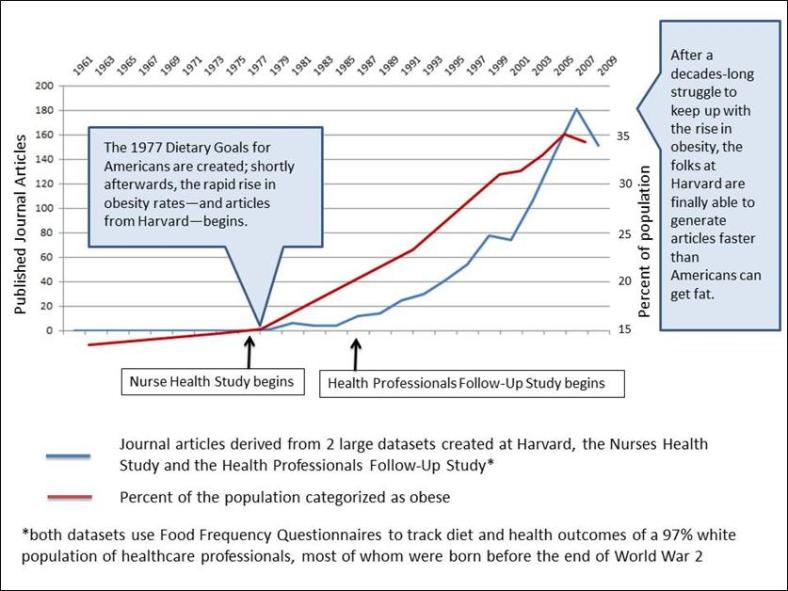

Around the late 70s or early 80s, there were sudden and rapid changes in America’s food supply and food choices and similar sudden and rapid changes in our health. How these two phenomena are related remains a matter of debate. It doesn’t matter if you’re Marion Nestle and you think the problem is calories or if you’re Gary Taubes and you think the problem is carbohydrate—both of those things increased in our food supply. (Whether or not the problem is fat is an open debate; food availability data points to an increase in added fats and oil, the majority of which are, ironically enough, the “healthy” monounsaturated kind; consumption data points to a leveling off of overall fat intake and a decrease in saturated fat—not a discrepancy I can solve here.) What seems to continue to mystify people is why this changed occurred so rapidly at this specific point in our food and health history.

Personally responsible or helplessly victimized?

At one time, it was commonly thought that obesity was a matter of personal responsibility and that our collective sense of willpower took a nosedive in the 80s, but nobody could ever explain quite why. (Perhaps a giant funk swept over the nation after The Muppet Show got cancelled, and we all collectively decided to console ourselves with Little Debbie Snack Cakes and Nickelodeon?) But because this approach is essentially industry-friendly (Hey, says Big Food, we just make the stuff!) and because no one has any explanation for why nearly three-quarters of our population decided to become fat lazy gluttons all at once (my Muppet Show theory notwithstanding) or for the increase of obesity among preschool children (clearly not affected by the Muppet Show’s cancellation), public health pundits and media-appointed experts have decided that obesity is no longer a matter of personal responsibility. Instead the problem is our “obesogenic environment,” created by the Big Bad Fast Processed Fatty Salty Sugary Food Industry.

Even though it is usually understood that a balance between supply and demand creates what happens in the marketplace, Michael Pollan has argued that it is the food industry’s creation of cheap, highly-processed, nutritionally-bogus food that has caused the rapid rise in obesity. If you are a fan of Pollanomics, it seems obvious that food industry—on a whim?—made a bunch of cheap tasty food, laden with fatsugarsalt, hoping that Americans would come along and eat it. And whaddaya know? They did! Sort of like a Field of Dreams only with Taco-flavored Doritos.

As a result, obesity has become a major public health problem.

Just like it was in 1952.

Helen Lee in thought-provoking article, The Making of the Obesity Epidemic (it is even longer than one of my blog posts, but well worth the time) describes how our obesity problem looked then:

“It is clear that weight control is a major public health problem,” Dr. Lester Breslow, a leading researcher, warned at the annual meeting of the western branch of the American Public Health Association (APHA).

At the national meeting of the APHA later that year, experts called obesity “America’s No. 1 health problem.”

The year was 1952. There was exactly one McDonald’s in all of America, an entire six-pack of Coca-Cola contained fewer ounces of soda than a single Super Big Gulp today, and less than 10 percent of the population was obese.

In the three decades that followed, the number of McDonald’s restaurants would rise to nearly 8,000 in 32 countries around the world,

sales of soda pop and junk food would explode — and yet, against the fears and predictions of public health experts, obesity in the United States hardly budged. The adult obesity rate was 13.4 percent in 1960. In 1980, it was 15 percent. If fast food was making us fatter, it wasn’t by very much.Then, somewhat inexplicably, obesity took off.”

It is this “somewhat inexplicably” that has me awake at night gnashing my teeth.

And what is Government going to do about it?

I wonder how “inexplicable” it would be to Ms. Lee had she put these two things together:

(In case certain peoples have trouble with this concept, I’ll type this very slowly and loudly: I’m not implying that the Dietary Guidelines “caused” the rise in obesity; I am merely illustrating a temporal relationship of interest to me, and perhaps to a few billion other folks. I am also not implying that a particular change in diet “caused” the rise in obesity. My focus is on the widespread and encompassing effects that may have resulted from creating one official definition of “healthy food choices to prevent chronic disease” for the entire population.)

Right now we are hearing calls from every corner for the government to create or reform policies that will reign in industry and “slim down the nation.” Because we’d never tried that before, right?

When smoking was seen as a threat to the health of Americans, the government issued a definitive report outlining the science that found a connection between smoking and risk of chronic disease. Although there are still conspiracy theorists that believe that this has all been a Big Plot to foil the poor widdle tobacco companies, in general, the science was fairly straightforward. Cigarette smoking—amount and duration—is relatively easy to measure, and the associations between smoking and both disease and increased mortality were compelling and large enough that it was difficult to attribute them to methodological flaws.

Notice that Americans didn’t wait around for the tobacco industry to get slapped upside the head by the FDA’s David Kessler in the 1990s. Tobacco use plateaued in the 1950s as scientists began to publicize reports linking smoking and cancer. The decline in smoking in America began in earnest with the release of Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General in 1964. A public health campaign followed that shifted social norms away from considering smoking as an acceptable behavior, and smoking saw its biggest declines before litigation and sanctions against Big Tobacco happened in the 1990s.

Been there, done that, failed miserably.

In a similar fashion, the 1977 Dietary Goals were the culmination of concerns about obesity that had begun decades before, joined by concerns about heart disease voiced by a vocal minority of scientists led by Ancel Keys. Declines in red meat, butter, whole milk and egg consumption had already begun in response to fears about cholesterol and saturated fat that originated with Keys and the American Heart Association—which used fear of fat and the heart attacks they supposedly caused as a fundraising tactic, especially among businessmen and health professionals, whom they portrayed as especially susceptible to this disease of “successful civilization and high living.” The escalation of these fears—and declines in intake of animal foods portrayed as especially dangerous—picked up momentum when Senator George McGovern and his Select Senate Committee created the 1977 Dietary Goals for Americans. It was thought that, just as we had “tackled” smoking, we could create a document advising Americans on healthy food choices and compliance would follow. But issue was a lot less straightforward.

To begin with, when smoking was at its peak, only around 40% of the population smoked. On the other hand, we expect that approximately 100% of the population eats.

In addition, the anti-smoking campaigns of the 1960s and 1970s built on a long tradition of public health messages—originating with the Temperance movement—that associated smoking with dirty habits, loose living, and moral decay. It was going to be much harder to fully convince Americans that traditional foods typically associated with robust good health, foods that the US government thought were so nutritionally important that in the recent past they had been “saved” for the troops, were now suspect and to be avoided.

Where the American public had once been told to save “wheat, meat, and fats” for the soldiers, they now had to be convinced to separate the “wheat” from the “meat and fats” and believe that one was okay and the others were not.

To do this, public health leaders and policy makers turned to science, hoping to use it just as it had been used in anti-smoking arguments. Frankly, however, nutrition science just wasn’t up to the task. Linking nutrition to chronic disease was a field of study that would be in its infancy after it grew up a bit; in 1977, it was barely embryonic. There was little definitive data to support the notion that saturated fat from whole animal foods was actually a health risk; even experts who thought that the theory that saturated fat might be linked to heart disease had merit didn’t think there was enough evidence to call for dramatic changes in American’s eating habits.

The scientists who were intent on waving the “fear of fat” flag had to rely on observational studies of populations (considered then and now to be the weakest form of evidence), in order to attempt to prove that heart disease was related to intake of saturated fat (upon closer examination, these studies did not even do that).

Nutrition epidemiology is a soft science, so soft that it is not difficult to shape it into whatever conclusions the Consistent Public Health Message requires. In large-scale observational studies, dietary habits are difficult to measure and the results of Food Frequency Questionnaires are often more a product of wishful thinking than of reality. Furthermore, the size of associations in nutrition epidemiological studies is typically small—an order of magnitude smaller than those found for smoking and risk of chronic disease.

But nutrition epidemiology had proved its utility in convincing the public of the benefits of dietary change in the 70s and since then has become the primary tool—and the biggest funding stream (this is hardly coincidental)—for cementing in place the Consistent Public Health Message to reduce saturated fat and increase grains and cereals.

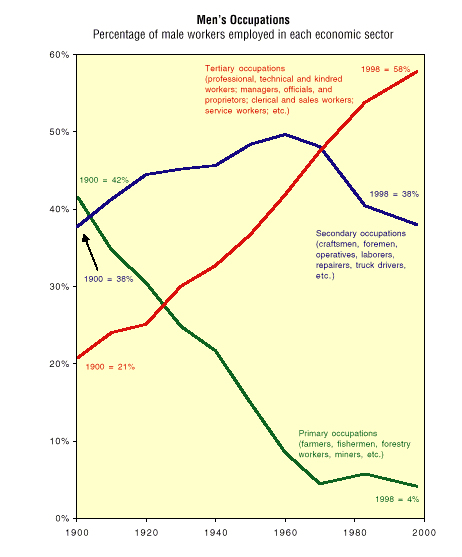

There is no doubt that the dramatic dietary change that the federal government was recommending was going to require some changes from the food industry, and they appear to have responded to the increased demands for low-fat,whole grain products with enthusiasm. Public health recommendations and the food fears they engendered are (as my friend James Woodward puts it) “a mechanism for encouraging consumers to make healthy eating decisions, with the ultimate goal of improving health outcomes.” Experts like Kelly Brownell and Marion Nestle decry the tactics used by the food industry of taking food components thought to be “bad” out of products while adding in components thought to be “good,” but it was federal dietary recommendations focusing above all else on avoiding saturated fat, cholesterol, and salt that led the way for such products to be marketed as “healthy” and to become acceptable to a confused, busy, and anxious public. The result was a decrease in demand for red meat, butter, whole milk and egg, and an increase in demand for low-saturated fat, low-cholesterol, and “whole” grain products. Minimally-processed animal-based products were replaced by cheaply-made, highly-processed plant-based products, which food manufacturers could market as healthy because, according to our USDA/HHS Dietary Guidelines, they were healthy.

The problem lies in the fact that—although these products contained less of the “unhealthy” stuff Americans were supposed to avoid—they also contained less of our most important nutrients, especially protein and fat-soluble vitamins. We were less likely to feel full and satisfied eating these products, and we were more likely to snack or binge—behaviors that were also fully endorsed by the food industry.

Between food industry marketing and the steady drumbeat of media messages explaining just how deadly red meat and eggs are (courtesy of population studies from Harvard, see above), Americans got the message. About 36% of the population believe that UFOs are real; only 25% believe that there’s no link between saturated fat and heart disease. We are more willing to believe that we’ve been visited by creatures from outer space than we are to believe that foods that humans have been eating ever since they became human have no harmful effects on health. But while industry has certainly taken advantage of our gullibility, they weren’t the ones who started those rumors, and they should not be shouldering all of the blame for the consequences.

Fixing it until it broke

Back in 1977, we were given a cure that didn’t work for diseases that we didn’t have. Then we spent billions in research dollars trying to get the glass slipper to fit the ugly stepsister’s foot. In the meantime, the food industry has done just what we would expect it to do, provide us with the foods that we think we should eat to be healthy and—when we feel deprived (because we are deprived)—with the foods we are hungry for.

We can blame industry, but as long as food manufacturers can take any mixture of vegetable oils and grain/cereals and tweak it with added fiber, vitamins, minerals, a little soy protein or maybe some chicken parts, some artificial sweeteners and salt substitutes, plus whatever other colors/preservatives/stabilizers/flavorizers they can get away with and still be able to get the right profile on the nutrition facts panel (which people do read), consumers–confused, busy, hungry–are going to be duped into believing what they are purchasing is “healthy” because–in fact–the government has deemed it so. And when these consumers are hungry later—which they are very likely to be—and they exercise their rights as consumers rather than their willpower, who should we blame then?

There is no way around it. Our dietary recommendations are at the heart of the problem they were created to try to reverse. Unlike the public health approach to smoking, we “fixed” obesity until it broke for real.