If you have been following any of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee’s meetings (who does that anyway? I mean, unless you are a total geek like I am), then you might have noticed that the next Guidelines seem very likely to continue to promote the same nutritional advice that has proven largely ineffective for more than 35 years.

In my other, not-quite-so-snarky, life, I am not Wonder Woman (but oh, what I wouldn’t give for a pair of bracelets of submission). However, I am director of the Healthy Nation Coalition, a loose affiliation of healthcare and public health professionals, scientists, and concerned citizens who think it is time we did nutrition a little differently. Right now, we are creating a coalition of supporters to speak out against the direction the current 2015 Dietary Guidelines are taking and to offer an alternative approach.

This letter will be delivered to the Secretaries of the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services, selected policymakers, and interested media outlets. We hope to add to the momentum that has been building in the national media calling for a change in our national dietary guidance (see Nina Teicholz’ book, Big Fat Surprise, and her recent op-ed in the Wall Street Journal).

The letter is copied below (or you can use this link to the pdf–the pdf is where all the citations are, because I know how you love citations).

If you wish to sign on, you can use this quick form to add your information to the letter. If you’re interested, but don’t want to read the whole boring letter, check out Mark Sisson’s blog post about it. It’s lots more fun.

In a nutshell, we are asking for Dietary Guidelines that are geared toward the general public and focused on adequate essential nutrition.

This is not a call for low-carb, high-fat dietary recommendations, or paleo ones, and it takes no stance on the whole “calories in, calories out” versus hormonal regulation etc. etc. issue. So if you want to criticize this approach, don’t start bitching about low-carb diets or CICO, or I’ll know that you haven’t bothered to actually read this and I won’t feel guilty about deleting your comments. Beyond that, if you have genuine objections to this approach, suggest a better one–or go away. What we are doing now isn’t working. What we need is productive conversation about what to do differently.

Healthy Nation Coalition Letter – 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

Dear Secretary Burwell and Secretary Vilsack,

At the conclusion of the sixth meeting of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC), we write to express concern about the state of federal nutrition policy and its long history of failure in preventing the increase of chronic disease in America. The tone, tenor, and content of the DGAC’s public meetings to date suggest that the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) will perpetuate the same ineffective federal nutrition guidance that has persisted for nearly four decades but has not achieved positive health outcomes for the American public.

We urge you to adhere to the initial Congressional mandate that the DGA act as “nutritional and dietary information and guidelines for the general public” and are “based on the preponderance of the scientific and medical knowledge which is current at the time the report is prepared.”

Below we lay out specific objections to the DGA:

· they have contributed to the increase of chronic diseases;

· they have not provided guidance compatible with adequate essential nutrition;

· they represent a narrow approach to food and nutrition inconsistent with the nation’s diverse cultures, ethnicities, and socioeconomic classes;

· they are based on weak and inconclusive scientific data;

· and they have expanded their purpose to issues outside their original mandate.

As you prepare to consider the 2015 DGAC’s recommendations next year, we urge you to fulfill your duty to create the dietary foundation for good health for all Americans by focusing on adequate essential nutrition from whole, nourishing foods, rather than replicating guidance that is clearly failing.

The DGA have contributed to the rapid rise of chronic disease in America.

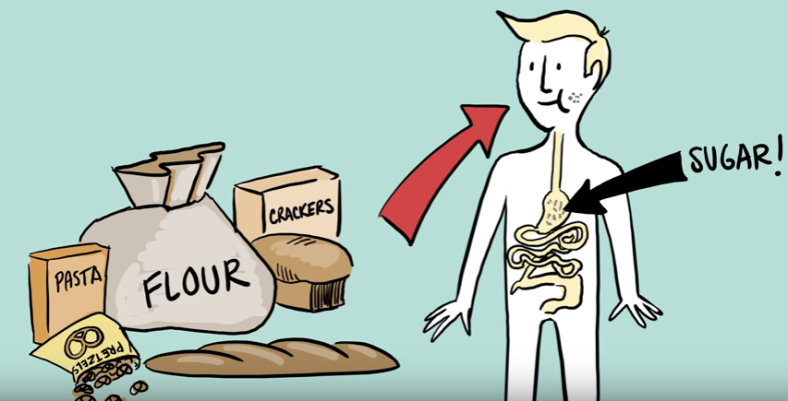

In 1977, dietary recommendations (called Dietary Goals) created by George McGovern’s Senate Select Committee advised that, in order to reduce risk of chronic disease, Americans should decrease their intake of saturated fat and cholesterol from animal products and increase their consumption of grains, cereal products, and vegetable oils. These Goals were institutionalized as the DGA in 1980, and all DGA since then have asserted this same guidance. During this time period, the prevalence of heart failure and stroke has increased dramatically. Rates of new cases of all cancers have risen. Most notably, rates of diabetes have tripled. In addition, although body weight is not itself a measure of health, rates of overweight and obesity have increased dramatically. In all cases, the health divide between black and white Americans has persisted or worsened.

While some argue that Americans have not followed the DGA, all available data show Americans have shifted their diets in the direction of the recommendations: consuming more grains, cereals, and vegetable oils, while consuming less saturated fat and cholesterol from whole foods such as meat, butter, eggs, and full-fat milk. Whether or not the public has followed all aspects of DGA guidance does not absolve the U.S. Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Health and Human Services (DHHS) from ensuring that the dietary guidance provided to Americans first and foremost does no harm.

The DGA fail to provide guidance compatible with essential nutrition needs.

The 1977 Dietary Goals marked a radical shift in federal dietary guidance. Before then, federal dietary recommendations focused on foods Americans were encouraged to eat in order to acquire adequate nutrition; the DGA focus on specific food components to limit or avoid in order to prevent chronic disease. The DGA have not only failed to prevent chronic disease, in some cases, they have failed to provide basic guidance consistent with nutritionally adequate diets.

· Maillot, Monsivais, and Drewnowski (2013) showed that the 2010 DGA for sodium were incompatible with potassium guidelines and with nutritionally adequate diets in general.

· Choline was recognized as an essential nutrient in 1998, after the DGA were first created. It is crucial for healthy prenatal brain development. Current choline intakes are far below adequate levels, and choline deficiency is thought to contribute to liver disease, atherosclerosis and neurological disorders. Eggs and meat, two foods restricted by current DGA recommendations, are important sources of choline. Guidance that limits their consumption thus restricts intake of adequate choline.

· In young children, the reduced fat diet recommend by the DGA has also been linked to lower intakes of a number of important essential nutrients, including calcium, zinc, and iron.

Following USDA and DHHS guidance should not put the most vulnerable members of the population at risk for nutritional inadequacy. DGA recommendations should be emphasizing whole foods that provide essential nutrition, rather than employing a reductionist approach based on single food components to exclude these foods from the diet.

The DGA’s narrow approach to food and health is inappropriate for a diverse population.

McGovern’s 1977 recommendations were based on research and food patterns from middle class Caucasian American populations. Since then, diversity in America has increased, while the DGA have remained unchanged. DGA recommendations based on majority-white, high socioeconomic status datasets have been especially inappropriate for minority and low-income populations. When following DGA recommendations, African American adults gain more weight than their Caucasian counterparts, and low-income individuals have increased rates of diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol. Long-standing differences in environmental, genetic and metabolic characteristics may mean recommendations that are merely ineffective in preventing chronic disease in white, middle class Americans are downright detrimental to the long-term health of black and low-income Americans.

The DGA plant-based diet not only ignores human biological diversity, it ignores the diversity of American foodways. DGA guidance rejects foods that are part of the cultural heritage of many Americans and indicates that traditional foods long considered to be important to a nourishing diet should be modified, restricted, or eliminated altogether: ghee (clarified butter) for Indian Americans; chorizo and eggs for Latino Americans; greens with fatback for Southern and African Americans; liver pâtés for Jewish and Eastern European Americans.

Furthermore, recommendations to prevent chronic disease that focus solely on plant-based diets is a blatant misuse of public health authority that has stymied efforts of researchers, academics, healthcare professionals, and insurance companies to pursue other dietary approaches adapted to specific individuals and diverse populations, specifically, the treatment of diabetes with reduced-carbohydrate diets that do not restrict saturated fat. In contradiction of federal law, the DGA have had the effect of limiting the scope of medical nutrition research sponsored by the federal government to protocols in line with DGA guidance.

The DGA are not based on the preponderance of current scientific and medical knowledge.

The science behind the current DGA recommendations is untested and inconsistent. Scientific disagreements over the weakness of the evidence used to create the 1977 Dietary Goals have never been settled. Recent published accounts have raised questions about whether the scientific process has been undermined by politics, bias, institutional inertia, and the influence of interested industries.

Significant scientific controversy continues to surround specific recommendations that:

1. Dietary saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease: Two recent meta-analyses concluded there is no strong scientific support for dietary recommendations that restrict saturated fat. Studies cited by the 2010 DGAC Report demonstrate that in some populations, lowering dietary saturated fat actually worsens some biomarkers related to heart disease.

2. Dietary cholesterol increases the risk of heart disease: Due to a lack of evidence, nearly all other Western nations have dropped their limits on dietary cholesterol. In 2013, a joint panel of the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology did the same.

3. Polyunsaturated vegetable oils reduce the risk of heart disease and should be consumed as the primary source of dietary fat: Recent research renews concerns raised in response to the 1977 Dietary Goals that diets high in the omega-6 fatty acids present in vegetable oils may actually increase risk of chronic disease or death.

4. A diet high in carbohydrate, including whole grains, reduces risk of chronic disease: Clinical trials have demonstrated that diets with lower carbohydrate content improve risk factors related to heart disease and diabetes. Janet King, Chair of the 2005 DGAC, has stated that “evidence has begun to accumulate suggesting that a lower intake of carbohydrate may be better for cardiovascular health.”

5. A low-sodium diet reduces risk of chronic disease: A 2013 Institute of Medicine report concludes there is insufficient evidence to recommend reducing sodium intake to the very low levels set by the DGA for African-Americans of any age and adults over 50.

In all of these cases, contradictory evidence has been ignored in favor of maintaining outdated recommendations that have failed to prevent chronic disease.

More generally, “intervention studies, where diets following the Dietary Guidelines are fed long-term to human volunteers, do not exist,” and food patterns recommended by the DGA “have not been specifically tested for health benefits.” The observational research being used for much of the current DGAC activities may suggest possible associations between diet and disease, but such hypotheses must then be evaluated through rigorous testing. Applying premature findings to public health policy without adequate testing may have resulted in unintended negative health consequences for many Americans.

The DGA have overstepped their original purpose.

The DGA were created to provide nutrition information to all Americans. However, the current 112-page DGA, with 29 recommendations, are considered too complex for the general public and are directed instead at policymakers and healthcare professionals, contradicting their Congressional mandate.

Federal dietary guidance now goes far beyond nutrition information. It tells Americans how much they should weigh and how to lose weight, even recommending that each American write down everything that is eaten on a daily basis. This focus on obesity and weight loss has contributed to extensive and unrecognized “collateral damage”: fat-shaming, eating disorders, discrimination, and poor health from restrictive food habits. At the same time, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control have shown that overweight and obese people are often as healthy as their “normal” weight counterparts. Guidance related to body weight should meet individual health requirements and be given by a trained healthcare practitioner, not be dictated by federal policy.

The DGA began as an unmandated consumer information booklet. They are now a powerful political document that regulates a vast array of federal programs and services, dictates nationwide nutrition standards, influences agricultural policies and health-related research, and directs how food manufacturers target consumer demand. Despite their broad scope, the DGA are subject to no evaluation or accountability process based on health outcomes. Such an evaluation would demonstrate that they have failed to fulfill their original goal: to decrease rates of chronic disease in America.

Despite this failure, current DGAC proceedings point to an expansion of their mission into sustainable agriculture and environmental concerns. While these are important issues, they demonstrate continued “mission creep” of the DGA. The current narrow DGA focus on plant-based nutrition suggests a similarly biased approach will be taken to environmental issues, disregarding centuries of traditional farming practices in which livestock play a central role in maintaining soil quality and ecological balance. Instead of warning Americans not to eat eggs and meat due to concerns about saturated fat, cholesterol, and obesity, it is foreseeable that similar warnings will be given, but for “environmental” reasons. This calls for an immediate refocusing of the purpose of the DGA and a return to nutritional basics.

Solution: A return to essential nutrition guidance

As our nation confronts soaring medical costs and declining health, we can no longer afford to perpetuate guidelines that have failed to fulfill their purpose. Until and unless better scientific support is secured for recommendations regarding the prevention of chronic disease, the DGA should focus on food-based guidance that assists Americans in acquiring adequate essential nutrition.

Shifting the focus to food-based guidance for adequate essential nutrition will create DGA that:

· are based on universally accepted and scientifically sound nutritional principles: Although more knowledge is needed, the science of essential nutrient requirements is firmly grounded in clinical trials and healthcare practice, as well as observational studies.

· apply to all Americans: Essential nutrition requirements are appropriate for everyone. Lack of essential nutrients will lead without exception to diseases of deficiency.

· include traditionally nourishing foods: A wide variety of eating patterns can provide adequate essential nutrition; no nourishing dietary approaches or cultural food traditions would be excluded or discouraged.

· expand opportunities for research: With dietary guidance focused on adequate essential nutrition, researchers, healthcare providers, and insurance companies may pursue dietary programs and practices tailored to individual risk factors and diverse communities without running afoul of the DGA and while ensuring that basic nutrition needs are always met.

· direct attention towards health and well-being: Focus will be directed away from intermediate markers, such as weight, which may be beyond individual control, do not consistently predict health outcomes, and are best dealt with in a healthcare setting.

· are clear, concise, and useful to the public: Americans will be able to understand and apply such guidance to their own dietary patterns, minimizing the current widespread confusion and resentment resulting from federal dietary guidance that is poorly grounded in science.

It is the duty of USDA and DHHS leadership to end the use of controversial, unsuccessful and discriminatory dietary recommendations. USDA and DHHS leadership must refuse to accept any DGA that fail to establish federal nutrition policy based on the foundation of good health: adequate essential nutrition from wholesome, nourishing foods. It is time to create DGA that work for all Americans.