This is the first of a series looking at what does and doesn’t matter when it comes to nutrition policy. When I started out on this adventure, I thought that science would give me the answers to the questions I had about why public health and clinical recommendations for nutrition were so limited. Silly me. The science part is easy. But policy, politics, economics, industry, media framing, the scientific bureaucracy, cultural bias—now that stuff is crazy complicated. It’s like an onion: when you start peeling back the layers, you just want to cry. I am also honored to say that this post is part of the Diversity in Science Carnival on Latino / Hispanic Health: Science and Advocacy

This is the first of a series looking at what does and doesn’t matter when it comes to nutrition policy. When I started out on this adventure, I thought that science would give me the answers to the questions I had about why public health and clinical recommendations for nutrition were so limited. Silly me. The science part is easy. But policy, politics, economics, industry, media framing, the scientific bureaucracy, cultural bias—now that stuff is crazy complicated. It’s like an onion: when you start peeling back the layers, you just want to cry. I am also honored to say that this post is part of the Diversity in Science Carnival on Latino / Hispanic Health: Science and Advocacy

When we began investigating relationships between diet and chronic disease, we didn’t pay much attention to race. The longest-running study of the relationship between dietary factors and chronic disease is the Framingham Heart Study, a study made up entirely of white, middle-class participants. Since 1951, the Framingham study has generated over 2 thousand journal articles and retains a central place in the creation of public health nutrition policy recommendations for all Americans.

More recent datasets—especially the large ones—are nearly as demographically skewed.

The Nurses’ Health Study is 97% Caucasian and consists of 122,000 married registered nurses who were between the ages of 30 and 55 when the study began in 1976. An additional 116,686 nurses ages 25 – 42 were added in 1989, but the racial demographics remained unchanged.

The Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study began in 1986, as a complementary dataset to the Nurses’ Health Study. It is 97% Caucasian and consists, as the name suggests, of 51, 529 men who were health professionals, aged 40-75, when the study began.

The Physicians’ Health Study began in 1982, with 29, 071 men between the ages of 40-84. The second phase started in 1997, adding men who were then over 50. Of participants whose race is indicated, 91% are Caucasian, 4.5% are Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% are Hispanic, and less than 1% are African-American or American Indian. I have detailed information about the racial subgroups of this dataset because I had to write the folks at Harvard and ask for them. Race was of such little interest that the racial composition of the participants is never mentioned in the articles generated from this dataset.

Over the years, these three mostly-white datasets have generated more journal articles than five of the more diverse datasets all put together.* These three datasets, all administered by Harvard, have been used to generate some of the more sensationalist nutrition headlines of the past few years–red meat kills, for instance–with virtually no discussion about the fact that the findings apply to a population–mostly white, middle to upper middle class, well-educated, health professionals, most of whom who were born before the atomic bomb–to which most of us do not belong.

Although we did begin to realize that race and other characteristics might actually matter with regard to health (hence the existence of datasets with more diversity), we can’t really fault those early researchers for creating such lopsided datasets. At that point, not only was the US more white than it is now, scientific advances that would reveal more about how our genetic background might affect health had not yet been developed. We had not yet mapped the human genome; epigenetics (the study of the interaction between environmental inputs and the expression of genetic traits) was in its infancy, and biochemical individuality was little more than a glimmer in Roger Williams’ eye.

Socially, culturally, and I think, scientifically, we were all inclined to want to think that everyone was created equal, and this “equality” extended to how our health would be affected by food. Stephen Jay Gould’s 1981 book, The Mismeasure of Man, critiqued the notion that “the social and economic differences between human groups—primarily races, classes, and sexes—arise from inherited, inborn distinctions and that society, in this sense, is an accurate reflection of biology.” In the aftermath of the civil rights movement, with its embarrassingly racist behavior on the part of some representatives of the majority race and the heartbreaking violence over differences in something as superficial as skin color, it was patently unhip to suggest that racial differences were anything more than just skin deep.

But does that position still serve us now?

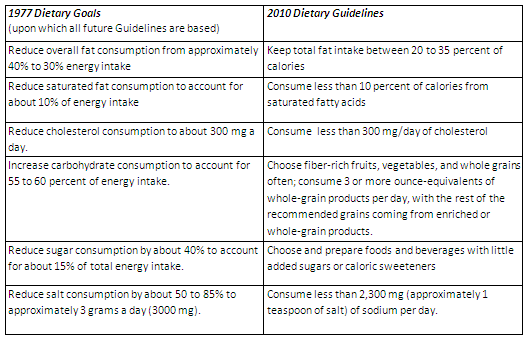

In the past 35 years, our population has become more diverse and nutrition science has become more nuanced—but our national nutrition recommendations have stayed exactly the same. The first government-endorsed dietary recommendations to prevent chronic disease were given to the US public in 1977. These Dietary Goals for Americans told us to reduce our intake of dietary saturated fat and cholesterol and increase our intake of dietary carbohydrates, especially grains and cereals in order to prevent obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and stroke.

Since 1980, the decreases in hypertension and serum cholesterol—health biomarkers—have been linked to Guidelines-directed dietary changes in the US population [1, 2, 3, 4].

“Age-adjusted mean Heart Disease Prevention Eating Index scores increased in both sexes during the past 2 decades, particularly driven by improvements in total grain, whole grain, total fat, saturated fatty acids, trans-fatty acids, and cholesterol intake.” [1]

However, with regard to the actual chronic diseases that the Dietary Guidelines were specifically created to prevent, the Dietary Guidelines have been a resounding failure. If public health officials are going to attribute victory on some fronts to Americans adopting dietary changes in line with the Guidelines, I’m not sure how to avoid the conclusion that they also played a part in the dramatic increases in obesity, diabetes, stroke, and congestive heart failure.

If the Dietary Guidelines are a failure, why have policy makers failed to change them?

It is not as if there is an overwhelming body of scientific evidence supporting the recommendations in the Guidelines. Their weak scientific underpinnings made the 1977 Dietary Goals controversial from the start. The American Society for Clinical Nutrition issued a report in 1979 that found little conclusive evidence for linking the consumption of fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol to heart disease and found potential risks in recommending a diet high in polyunsaturated fats [5]. Other experts warned of the possibility of far-reaching and unanticipated consequences that might arise from basing a one-size-fits-all dietary prescription on such preliminary and inconclusive data: “The evidence for assuming that benefits to be derived from the adoption of such universal dietary goals . . . is not conclusive and there is potential for harmful effects from a radical long-term dietary change as would occur through adoption of the proposed national goals” [6]. Are the alarming increases in obesity and diabetes examples of the “harmful effects” that were predicted? It does look that way. But at this point, at least one thing is clear: in the face of the deteriorating health of Americans and significant scientific evidence to the contrary, the USDA and HHS have continued to doggedly pursue a course of dietary recommendations that no reasonable assessment would determine to be effective.

But what does this have to do with race?

Maintaining the myth that a one-size diet approach works for everyone is fine if that one-size works for you—socially, financially, and in terms of health outcomes. The single positive health outcome associated with the Dietary Guidelines has been a decrease in heart attacks—but only for white people.

And if that one-size diet doesn’t fit in terms of health, if you end up with one of the other numerous adverse health effects that has increased in the past 35 years, if you’re a member of the mostly-white, well-educated, middle/upper-middle class demographic—you know, the one represented in the datasets that we continue to use as the backbone for our nutrition policy—you are likely to have the financial and social resources to eat differently from the Guideline recommendations should you choose to do so, to exercise as much as you need to, and to demand excellent healthcare if you get sick anyway. Even if you accept that these foods are Guidelines-recommended “healthy” foods, you are not stuck with the commodity crop-based processed foods for which our nutrition programs have become a convenient dumping ground.

In the meantime, low-income women, children, and minorities and older adults with limited incomes—you know, the exact population not represented in those datasets—remain the primary recipients of federal nutrition programs. Black, Hispanic, and American Indian kids are more likely to qualify for free or reduced-price school lunches; non-white participants make up 68% of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children enrollment. These groups have many fewer social, financial, and dietary options. If the food they’re given doesn’t lead to good health—and there is evidence that it does not—what other choices do they have?

When it comes to health outcomes in minorities and low-income populations, the “healthier” you eat, the less likely you are to actually be healthy. Among low-income children, “healthy eaters” were more likely to be obese than “less-healthy eaters,” despite similar amounts of sedentary screen time. Among low-income adults, “healthy eaters” were more likely to have health insurance, watch less television, and to not smoke. Yet the “healthy eaters” had the same rates of obesity as the “less-healthy heaters” and increased rates of diabetes, even after adjustment for age.

These associations don’t necessarily indicate a cause-effect relationship between healthy eating and health problems. But there are other indications that being a “healthy eater” according to US Dietary Guidelines does not result in good health. Despite adherence to “healthy eating patterns” as determined by the USDA Food Pyramid, African American children remain at higher risk for development of diabetes and prediabetic conditions, and African American adults gain weight at a faster pace than their Caucasian counterparts [7,8].

Adjusted 20-year mean weight change according to low or high Diet Quality Index (DQI) scores [8]

Clearly, we need to expand our knowledge of how food and nutrients interact with different genetic backgrounds by specifically studying particular racial and ethnic subpopulations. Social equality does not negate small but significant differences in biology. But it won’t matter how much diversity we build into our study populations if the conclusions arrived at through science are discarded in favor of maintaining public health nutrition messages created when most human beings studied were of the adult, mostly white, mostly male variety.

Right now the racial demographics of the participants in an experimental trial or an observational study dataset doesn’t matter, and the reason it doesn’t is because the science doesn’t matter. What really matters? Maintaining a consistent public health nutrition message—regardless of its affect on the health of the population—that means never having to say you’re sorry for 35 years of failed nutritional guidance.

*ARIC – Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (1987), 73% white; MESA – Multi Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (2000), 38% white, 28% African American, 12% Chinese, 22% Hispanic; CARDIA – Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (1985), 50% black, 50% white; SHS – Strong Heart Study (1988), 100% Native American; BWHS – Black Women’s Health Study(1995), 100% black women.

References:

1. Lee S, Harnack L, Jacobs DR Jr, Steffen LM, Luepker RV, Arnett DK. Trends in diet quality for coronary heart disease prevention between 1980-1982 and 2000-2002: The Minnesota Heart Survey. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007 Feb;107(2):213-22.

2. Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Grodstein F, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Willett WC. Trends in the incidence of coronary heart disease and changes in diet and lifestyle in women. N Engl J Med. 2000 Aug 24;343(8):530-7.

3. Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Apr 14;168(7):713-20. Erratum in: Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jun 23;168(12):1276.

4. Briefel RR, Johnson CL. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:401-31. Secular trends in dietary intake in the United States.

5. Broad, WJ. NIH Deals Gingerly with Diet-Disease Link. Science, New Series, Vol. 204, No. 4398 (Jun. 15, 1979), pp. 1175-1178.

6. American Medical Association. Dietary goals for the United States: statement of The American Medical Association to the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, United States Senate. R I Med J. 1977 Dec;60(12):576-81.

7. Lindquist CH, Gower BA, Goran MI Role of dietary factors in ethnic differences in early risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Mar; 71(3):725-32.

8. Zamora D, Gordon-Larsen P, Jacobs DR Jr, Popkin BM. Diet quality and weight gain among black and white young adults: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study (1985-2005). American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010 Oct;92(4):784-93.

9. Hite AH, Berkowitz VG, Berkowitz K. Low-carbohydrate diet review: shifting the paradigm. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011 Jun;26(3):300-8. Review.