Nostalgia for a misremembered past is no basis for governing a diverse and advancing nation.

The truth is that I get most of my political insight from Mad Magazine; they offer the most balanced commentary by far. However, I’ve been very interested in the fallout from the recent election, much more so than I was in the election itself; it’s like watching a Britney Spears meltdown, only with power ties. I kept hearing the phrase “epistemic closure” and finally had to look it up. Now, whether or not the Republican party suffers from it, I don’t care (and won’t bother arguing about), but it undeniably describes the current state of nutrition. “Epistemic closure” refers to a type of close-mindedness that precludes any questioning of the prevailing dogma to the extent that the experts, leaders, and pundits of a particular paradigm:

“become worryingly untethered from reality”

“develop a distorted sense of priorities”

and are “voluntarily putting themselves in the same cocoon”

Forget about the Republicans. Does this not perfectly describe the public health leaders that are still clinging blindly to the past 35 years of nutritional policy? The folks at USDA/HHS live in their own little bubble, listening only to their own experts, pretending that the world they live in now can be returned to an imaginary 1970s America, where children frolicked outside after downing a hearty breakfast of sugarless oat cereal and grown-ups walked to their physically-demanding jobs toting homemade lunches of hearty rye bread and shiny red apples.

Remember when all the families in America got their exercise playing outside together—including mom, dad, and the maid? Yeah, me neither.

So let me rephrase David Frum’s quote above for my own purposes: Nostalgia for a misremembered past is no basis for feeding a diverse and advancing nation.

If you listen to USDA/HHS, our current dietary recommendations are a culmination of science built over the past 35 years on the solid foundation of scientific certainty translated into public health policy. But this misremembered scientific certainty wasn’t there then and it isn’t here now; the early supporters of the Guidelines were very aware that they had not convinced the scientific community that they had a preponderance of evidence behind them [1]. Enter the first bit of mommy-state* government overreach. When George McGovern’s (D) Senate Select Committee came up with the 1977 Dietary Goals for Americans, it was a well-meaning approach to not only reduce chronic disease, a clear public health concern, but to return us all to a more “natural” way of eating. This last bit of ideology reflected a secular trend manifested in the form of the Dean Ornish-friendly Diet for a Small Planet, a vegetarian cookbook that smushed the humanitarian and environmental concerns of meat-eating in with some flimsy nutritional considerations, promising that a plant-based diet was the best way to feed the hungry, save the planet, safeguard your health, and usher in the Age of Aquarius. This was a pop culture warm-fuzzy with which the “traditional emphasis on the biochemistry of disease” could not compete [2].

If you listen to some folks, the goofy low-fat, high-carb, calories in-calories out approach can be blamed entirely on this attempt of the Democrats to institutionalize food morality. But, let’s not forget that the stage for the Dietary Guidelines fiasco was set earlier by Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz, an economist with many ties to large agricultural corporations who was appointed by a Republican president. He initiated the “fencerow to fencerow” policies that would start the shift of farm animals from pastureland to feed lots, increasing the efficiency of food production because what corn didn’t go into cows could go into humans, including the oils that were a by-product of turning crops into animal feed. [Update: Actually, not so much Butz’s fault, as I’ve come to learn, because so many of these policies were already in place before he came along. Excellent article on this here.]

When Giant Agribusiness—they’re not stupid, y’know—figured out that industrialized agriculture had just gotten fairydusted with tree-hugging liberalism in the form of the USDA Guidelines, they must have been wetting their collective panties. The oil-refining process became an end in itself for the food industry, supported by the notion that polyunsaturated fats from plants were better for you than saturated fats from animals, even though evidence for this began to appear only after the Guidelines were already created and only through the status quo-confirming channels of nutrition epidemiology, a field anchored solidly in the crimson halls of Harvard by Walter Willett himself.

Between Earl Butz and McGovern’s “barefoot boys of nutrition,” somehow corn oil from refineries like this became more “natural” than the fat that comes, well, naturally, from animals.

And here we are, 35 years later, trying to untie a Gordian knot of weak science and powerful industry cemented together by the mutual embarrassment of both political orientations. The entrenched liberal ivory-tower interests don’t want look stupid by having to admit that the 3 decades of public health policy they created and have tried to enforce have failed miserably. The entrenched big-business-supporting conservative interests don’t want to look stupid by having to admit that Giant Agribusiness, whose welfare they protect, is now driving up government spending on healthcare by acting like the cigarette industry did in the past and for much the same reasons.

These overlapping/competing agendas have created the schizophrenic, conjoined twins of a food industry-vegatarian coalition, draped together in the authority of government policy. Here the vegans (who generally seem to be politically liberal rather than conservative, although I’m sure there are exceptions) play the part of a vocal minority of food fundamentalists whose ideology brooks no compromise. (I will defend eternally the right for a vegan–or any fundamentalist–to choose his/her own way of life; I draw the line at having it imposed on anyone else–and I squirm a great deal if someone asks me if that includes children.) The extent to which vegan ideology and USDA/HHS ideology overlap has got to be a strange bedfellow moment for each, but there’s no doubt that the USDA/HHS’s endorsement of vegan diets is a coup for both. USDA/HHS earns a politically-correct gold star for their true constituents in the academic-scientific-industrial complex, and vegans get the nutritional stamp of approval for a way of eating that, until recently, was considered by nutritionists to be inadequate, especially for children.

Like this chicken, the USDA/HHS loves vegans—at least enough to endorse vegan diets as a “healthy eating pattern.”

But if the current alternative nutrition movement is allegedly representing the disenfranchised eaters all over America who have been left out of this bizarre coalition, let us remember that, in many ways, the “alternative” is really just more of the same. If the McGovern hippies gave us “eat more grains and cereals, less meat and fat,” now the Republican/Libertarian-leaning low-carb/primaleo folks have the same idea only the other way around—and with the same justification. “Eat more meat and fat, fewer grains and cereals;” it’s a more “natural” way to eat.

As counterparts to the fundamentalist vegans, we have the Occupy Wall street folks of the alternative nutrition community—raw meaters who sleep on the floor of their caves and squat over their compost toilets after chi running in their Vibrams. They’re adorably sincere, if a little grubby, and they have no clue how badly all the notions they cherish would get beaten in a fight with the reality of middle-Americans trying to make it to a PTA meeting.

To paraphrase David Frum again, the way forward in food-health reform is collaborative work, and although we all have our own dietary beliefs, food preferences, and lifestyle idiosyncrasies, the immediate need is for a plan with just this one goal: we must emancipate ourselves from prior mistakes and adapt to contemporary realities.

Because the world in which we live is not the Brady Bunch world that the many of us in nutrition seem to think it is.

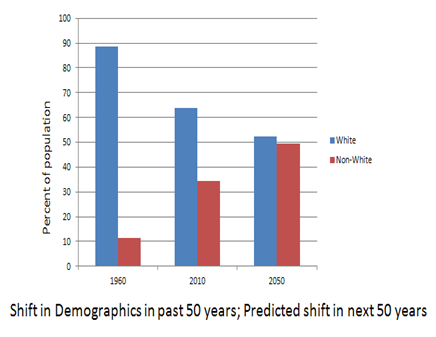

Frum makes the point that in 1980, when the Dietary Guidelines were first officially issued from the USDA, this was still an overwhelmingly white country. “Today, a majority of the population under age 18 traces its origins to Latin America, Africa, or Asia. Back then, America remained a relatively young country, with a median age of exactly 30 years. Today, over-80 is the fastest-growing age cohort, and the median age has surpassed 37.” Yet our nutrition recommendations have not changed from those originally created on a weak science base of studies done on middle-aged white people. To this day, we continue to make nutrition policy decisions on outcomes found in databases that are 97% white. The food-health needs of our country are far more diverse now, culturally and biologically. And another top-down, one-size-fits-all approach from the alternative nutrition community won’t address that issue any more adequately than the current USDA/HHS one.

For those who think the answer is to “just eat real food,” here’s another reality check: “In 1980, young women had only just recently entered the workforce in large numbers. Today, our leading labor-market worry is the number of young men who are exiting.” That means that unless these guys are exiting the workforce to go home and cook dinner, the idea that the solution to our obesity crisis lies in someone in each American household willingly taking up the mind-numbingly repetitive and eternally thankless chore of putting “real food” on the table for the folks at home 1 or more times a day for years on end—well, it’s as much a fantasy as Karl Rove’s Ohio outcome.

David Frum points out that “In 1980, our top environmental concerns involved risks to the health of individual human beings. Today, after 30 years of progress toward cleaner air and water, we must now worry about the health of the whole planetary climate system.” Today, our people and our environment are both sicker than ever. We can point our fingers at meat-eaters, but saying we now grow industrialized crops in order to feed them to livestock is like saying we drill for oil to make Vaseline. The fact that we can use the byproducts of oil extraction to make other things—like Vaseline or livestock feed—is a happy value-added efficiency in the system, no longer its raison d’etre. Concentrated vertical integration has undermined the once-proud tradition of land stewardship in farming. Giving this power back to farmers means taking some power away from Giant Agribusiness, and neither party has the political will to do that, especially when together they can demonize livestock-eating while promoting corn oil refineries.

And it’s not just our food system that has changed: “In 1980, 79 percent of Americans under age 65 were covered by employer-provided health-insurance plans, a level that had held constant since the mid-1960s. Back then, health-care costs accounted for only about one 10th of the federal budget. Since 1980, private health coverage has shriveled, leaving some 45 million people uninsured. Health care now consumes one quarter of all federal dollars, rapidly rising toward one third—and that’s without considering the costs of Obamacare.” That the plant-based diet that was institutionalized by liberal forces and industrialized by conservative ones is a primary part of this enormous rise in healthcare costs is something no one on either side of the table wants to examine. Diabetes—the symptoms of which are fairly easily reversed by a diet that excludes most industrialized food products and focuses on meat, eggs, and veggies—is the nightmare in the closet of both political ideologies.

David Frum quotes the warning from British conservative, the Marquess of Salisbury, “The commonest error in politics is sticking to the carcass of dead policies.”

Right now, it is in the best interest of both parties to stick to our dead nutrition policies and dump the ultimate blame on the individuals (we gave you sidewalks and vegetable stands–and you’re still fat! cry the Democrats; we let the food industry have free reign so you could make your own food choices–and you’re still fat! cry the Republicans). It’s a powerful coalition, resistant to change no matter who is in control of the White House or Congress.

What can be done about it, if anything? To paraphrase Frum once again, a 21st century food-health system must be economically inclusive, environmentally responsible, culturally modern, and intellectually credible.

We can start the process by stopping with the finger-pointing and blame game, shedding our collective delusions about the past and the present, and recognizing the multiplicity of concerns that must be addressed in our current reality. Let’s begin by acknowledging that—for the most part—the people in the spotlight on either side of the nutrition debate don’t represent the folks most affected by federal food-health policies. It is our job as leaders, in any party and for any nutritional paradigm, to represent those folks first, before our own interests, funding streams, pet theories, or personal ideologies. If we don’t, each group—from the vegatarians to folks at Harvard to the primaleos—runs the risk of suffering from its own embarrassing form of epistemic closure.

Let’s quit bickering and get to work.

**********************************************************

*This was too brilliant to leave buried in the comments section:

“Don’t you remember the phrase “wait til your father gets home”? You want to know what the state is? It’s Big Daddy. Doesn’t give a damn about the day to day scut, just swoops in to rescue when things get out of hand and then takes all the credit when the kids turn out well, whether it’s deserved or not. Equates spending money with parenting, too.”–from Dana

So from henceforth, all my “mommy-state” notions are hereby replaced with “Big Daddy,” a more accurate and appropriate metaphor. And I never metaphor I didn’t like.

References:

1. See Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs of the United States Senate. Dietary Goals for the United States. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1977b. Dr. Mark Hegsted, Professor of Nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health and an early supporter of the 1977 Goals, acknowledged their lack of scientific support at the press conference announcing their release: “There will undoubtedly be many people who will say we have not proven our point; we have not demonstrated that the dietary modifications we recommend will yield the dividends expected . . . ”

2. Broad, WJ. Jump in Funding Feeds Research on Nutrition. Science, New Series, Vol 204. No. 4397 (June 8, 1979). Pp. 1060-1061 + 1063-1064. In a series of articles in Science in 1979, William Broad details the political drama that allowed the “barefoot boys of nutrition” from McGovern’s committee to put nutrition in the hands of the USDA.

Reblogged this on it's the satiety and commented:

This is my first attempt at re-blogging. This is an important post and worthy of more than just a comment or posting to my facebook page. Lots of other good content on this site. Re-posted from Eathropology, by Adele Hite, MPH RD

I appreciate the honesty in your “first attempt at re-blogging”! I know the feeling well. My kids tease me about “blabbing on my blob” and “twitting on tweeter.” Thanks for the kind words and the re-post.

Adele,

Thanks for your most recent lovely comment-response and for your suggestion about becoming part of the solution. I have some excellent ideas to pursue, now, as a result of thinking much more about the critical ideas you discuss on your blog—and as a result of the many helpful perspectives you have shared so generously in your responses to comments.

Until recently, I had continued to think with the mindset of oppressive dominant discourses (wrongly legitimated by AMA, ADA, media, etc), even though I recognized the damaging cognitive dissonance that results from those discourses. Thus, for instance, I kept conceptualizing my current dietary practices in terms of “lower” or “reduced” carbohydrate—or “high” fat.

ARGH.

I finally realized that the concepts of “higher” and “lower” (fat or carb percentages) are socially constructed beliefs—beliefs which only become forms of social control and domination by means of the socially constructed power invested in those same oppressive dominant discourses. In other words, those constructs only WORK, in reality, as a means of continuing to legitimate (give power to) the prevailing harmful dietary paradigm(s).

It was like clearly seeing “the master’s tools” (Audre Lorde) for the first time, and understanding exactly why those tools “will never dismantle the master’s house.” And knowing exactly why new “tools” are crucial.

Thank you again. It feels enormously empowering to have your blog as a source of helpful information, a source of useful ideas and (perhaps best of all) a source of inspiration.

*hopefulandfree*

“It was like clearly seeing “the master’s tools” (Audre Lorde) for the first time, and understanding exactly why those tools “will never dismantle the master’s house.” And knowing exactly why new “tools” are crucial.”

I still have these moments–and every time still feels like the first time! When I realize that I’ve been stuck in a way of looking at the world that pits me against something or someone, when I feel like I’m not getting anywhere (where is it I’m going that I’m not getting???), or when I get hung up in trying to prove I’m “right” about something–and then I take a step back and remember that anything that separates me from my fellow humans (animosity, competition, despair) is a point scored for the machine, and the machine is, at its core, the master’s house.

[Lit Geek Aside: When I was in DC for my public health policy rotation, I stumbled across a book called Gone Away World by Nick Harkaway. Aside from being a wild, ninja-filled, sci-fi romp, its incisive commentary on “the machine” was a perfect counterpoint to life in DC–and just happened to exactly echo Jim Turner’s words to me. Long, cold winter coming up–you might enjoy it. Do just the right books ever land in your lap just when you need them? I don’t know if I am just receptive or lucky or what–happens to me all the time.]

I love the language you use in your latest post-“my own lived experience”–to capture that sense of “I am here” as you describe the whole carb/fat framing that you’ve so rightly called out. I struggle to explain how I eat now (“like a normal person” is what always comes to mind, but everybody thinks their own idiosyncratic way of eating is “normal”). High fat? compared to what? Low carb? compared to who? Vegetarian? I eat lots of vegetables! Local? I seldom leave town to eat. Real food? every now & then I like surreal food too . . .

Your insightful comments about hunger (here’s the link again fellow readers, it’s a great post) are tools that will go into my own toolbox as I carry this conversation forward. And I should add, it is voices like yours, and the tools they supply to the task at hand, that will help us dismantle the master’s house and build one where hunger is not a requirement for health.

interesting article and lots of informative replies. personally food is food when eating out you have to be selective, home cooked is not necessarily better unless you are using very wholesome ingredients and the like. homecooking increases the cost of living on most households simply because you have to add the cost of energy, labor, water usuage, and the like in the equation rather than just the actual cost of the food. also we have found it cheaper here in our situation to just eat sandwiches from subway making sure ot get lots of veggies, be selective in what breads to use and what type to get. when I compared the cost of the groceries and the cost of labor, electricity, clean up with water and labor for that, we are actually saving.

frankly I do love to cook however, but there are weeks that I do and our grocery bill almost doubles by the time I buy the wholesome ingredients. I do love to bake also and have found many wonderful lower carb high quality ingredients for my desserts. like almond flour, eggs of course, coconut oil, stuff like that. if I could cook more often I would.

but this idea of homecooked meals being considered a relgious/sustainable acceptable (as opposed to unsustaiable eating out) duty is silly. many resturants serve wholesome foods if you know where to look. once at a red lobster, I had a salmon steak grilled, with lots of green veggies and little parfair rice and salad. sounds pretty healthy to me.

so really it si about choices, making healthy choices according to your abilities, finanaces, needs etc. there is no one way is better or the other is, it depends on your circumstances.

as for the nanny state, it is agreed they need to stop imposing their ideas of right and wrong on others, when they can’t even figure it out for themslves or have more serious issues of their own behavior to deal with. they are meddlers in other people’s affairs and the bible condemns that. also jesus said not to worry about the straw in your brothers eye until you remove teh rafter (log) in your own, so people in gov/corp bullies need to take care of their own rafters first. maybe we should use another term instead of nanny state, this conveys a loving stewardship over the children, we are not children and we don’t need a nanny, do you?

All good points–and I think that many of my younger classmates who neither know how to cook nor have a grand desire to learn (because then that chore would be theirs in whatever household they end up in) would agree with you completely. We could argue the money cost/time cost/intangible value costs of the various “sources” for a meal endlessly–these things have different values for different folks–but the bottom line is somebody has to do it, and frequently, I don’t want that somebody to be me. I’ve found that there are a lot of women who feel like they’ve “escaped” the kitchen only to feel like they’re being bullied back into it by the Just Eat Real Food movement. I love that my husband has started sharing the cooking duties, but when we were talking at dinner about the responses to this post, he admitted that he would not want to have been the person in charge of the food brigade while the kids were growing up (he made a very bad, scary face at the thought).

I don’t think citizens need a nanny very often–it’s very difficult to legislate lifestyle choices that (theoretically) don’t affect others. There may be other aspects of our economy or our environment that could use a little more loving stewardship, but when it comes to creating policy to “improve” anything–air, water, trade balance, employment rates, and, of course, the food supply and our healthcare system–it gets messy fast and unintended consequences abound.

Great post.

Be content to live in the US, because here in Germany, we have five major parties, including conservatives, socialists, modernized communists, greens and libertarians.

Comprehensive insults are so much harder on this side of the big pond!

LOL. Yeah, that would have made my job a lot tougher! Thanks for the kind words.

Adele,

In your response, above, you write, “…the people in the machine are as much victims of the machine as the rest of us. It is something to remember.”

I have never heard this concept expressed quite that way–with such brutally blunt eloquence. It speaks to a critical truth that I hope to never forget. Without that full recognition of one another, we are lost as people.

*hopefulandfree*

Yeah, Jim told me that one day as I was in the middle of a full-on rant about the American Dietetics Association. It stopped me cold, because I realized how right he was. The women I knew who were in the ADA were good people, snagged by connections, money, a little bit of ego, a corner office, day-to-day responsibilities, and the rest of the things that are fine, really, until they aren’t. They were not living out their dreams, which I know they had, to truly help people (as scary and thankless as my work is sometimes, I do get to do this), and they frequently had to self-censor because to be true to themselves would mean trouble in the machine (I am constitutionally unable to do this, not always a good thing). We all make choices, but sometimes that slippery slope is just so gradual we end up trapped & don’t have the courage–or whatever it takes that you had–to yank ourselves out. To be other than humane to a person in that situation makes no sense. It would be like saying, yes, you are the machine so go act like it. Our mission should be to do just the opposite: yes, you are human, can we be human together?

Adele, you mention here that you are able “to truly help people” as a result of the specific work you currently do, which is “…scary and thankless…sometimes…”. I feel like I should recall your previous discussions on the subject, but I’m drawing a blank. Sorry. I would be grateful for a link–or a quick mention–about the specific kinds of work you do besides (of course) the educating, entertaining, informing and emotionally nurturing sustenance that you bring to your blog readers. 🙂

Like the women you mention in the ADA, who undoubtedly began with high hopes to help others and strong needs to share their feelings of compassion, I approached the nursing profession with a blind certainty that I would find, working as an RN, some small niche (somewhere) that wouldn’t require me to harm others or to harm myself (dehumanize, objectify or discount people’s lived experiences and feelings, for instance) but WOULD allow me to be of real service during peoples’ times of need (thus, to do or to provide necessary things for people, which they couldn’t do for themselves or provide on their own.)

I don’t know how to find that niche, and to be honest, I don’t even know where to start looking.

It seems like nursing has always been a “caring” profession that typically demands courage (and willingness to remain unappreciated), both of which I could muster or live with, in many cases—but nowadays it also seems to require the willing sacrifice of one’s own health-sustaining needs—with (for example) mandatory one to two years (minimum) in entry-level hospital nursing (12-hour shifts—often in understaffed and unsafe conditions) expected as some bizarre proof of worthiness or as evidence of complete socialization into a dysfunctional (harmful) or hostile work environment. I know. I probably sound hostile myself.

I guess I’m hoping that you (or a passing reader) might have some words of encouragement to offer, perhaps as one “care provider” to another, or maybe some resources you might be aware of for beginning nurses, like myself, who also have disability issues (which require a higher level of self care and greater flexibility in work options.) One might suppose that a “caring” profession would also strive to extend that most esteemed value (caring) towards its own members—but I have found that indifference holds rule more often than I could ever have imagined, for reasons I don’t fully understand. I realize you work in a different field, of course, but I’m learning that mutual aid, solidarity, and support often come from unexpected sources. 🙂

“educating, entertaining, informing and emotionally nurturing sustenance”–that’s the best work I do! My other “job” is Healthy Nation Coalition (“job” because I don’t get paid–yet–and because I couldn’t not do it, even if I didn’t have a fancy schmantzy title to go with it). I plan on making the world change & every day I get to do something that takes me in that direction. Today it was working on a book, connecting some other people who are working on the same issues I am, and trying to figure out if HNC wants to get involved in the Dietary Guidelines nomination process or just report on it. This year has been easier than the past few because I’m taking a year off from grad school. During that time, I had to muscle up my courage every day in order to just open my mouth in class and ask questions that I knew were provocative, but needed to be aired. Maybe I’m a weenie, but when I have to be in a roomful of willfully blind people and point out the elephant, or when I have to insist on integrity rather than just “playing nice” as we “girls” are still expected to do much of the time, I’m terrified. Believe it or not, I HATE confrontation. (I know, I picked the wrong path, right?)

When I worked in the Duke clinic, we had a lot of nurses as patients. Yes, self-care seems to be difficult to sustain in that profession. Your description reminds me of my early years as a high school teacher; there is almost a sadistic level of turfed work–remedial classes, crappy extracurricular activities, bus duty, after-school suspension supervision–that a new teacher is supposed to take on during those tender first years when we are just figuring out how to do our jobs. The thankless/low pay part is not a problem (see my current “job”), it’s the complete lack of control while shouldering full responsibility–the very definition of a situation designed to rip out your sanity. This is why those Teach for America contracts are two years long–after that there’s nothing left of the poor kid. I lasted 7 years and have the missing brain cells to prove it.

I understand the urge to be in that caring profession–to make things better for someone somewhere on a regular basis–it’s why I went into teaching, and it’s why I do what I do now, and why I plan to work again with patients as a nutritionist in the near, I hope, future. But, you already know this, you are of little use to others when you can’t or don’t care for yourself. But I don’t know of any specific resources for nurses or other healthcare providers–although clearly, they are needed.

This is going to sound a little silly at first: If there are in fact no resources like that out there for nurses, maybe you are the woman to create that network? I know it sounds all warmfuzzyish, but sometimes it is that sort of thing that leads to other (paying) positions that give you the chance to do the work you are trained to do while doing the work you are called to do. You certainly have the right mindset for it.

Reblogged this on In My Skinny Genes and commented:

“And here we are, 35 years later, trying to untie a Gordian knot of weak science and powerful industry cemented together by the mutual embarrassment of both political orientations. The entrenched liberal ivory-tower interests don’t want look stupid by having to admit that the 3 decades of public health policy they created and have tried to enforce have failed miserably. The entrenched big-business-supporting conservative interests don’t want to look stupid by having to admit that Giant Agribusiness, whose welfare they protect, is now driving up government spending on healthcare by acting like the cigarette industry did in the past and for much the same reasons.”

…I wish everybody would read Adele Hite’s blog.

These ARE the current staples of my everyday diet: butter, eggs, cream, full fat cheeses and yogurt, beef and chicken, including fatty cuts (and fish when available), peanut butter, berries (any kind, not choosy but cheapest from my own patch), tree fruit when in season from my small home orchard (apricots, plums, cherries, peaches and apples–3 kinds.) Throw in a few exotic pepper varieties, tomatillos, and tomatoes for salsa. A carrot now and then for flavor. Popcorn or nuts are most typical snacks. Daily treat: 90% dark chocolate (one full serving or more)

Current weight and health-related concerns: 160 lbs. Normal BP & glucose. Very rarely experience pain in back, neck, knee or shoulder–and only if severely overworked (say, sunup to sundown). No foot pain.

These WERE the current staples of my everyday diet in 2008 (and for 3 decades before then): whole grain everything (bread, muffins, pancakes, etc), brown rice; beans (black, pinto and red); fresh vegetables of diverse varieties (many of which I ate for “nutrition sake” but didn’t enjoy much unless sauteed in olive oil, which made me feel guilty), fruit (mostly apples, oranges and bananas), an occasional egg (non stick pan or boiled), a single serving of extra lean meat, skim milk products, non fat cheeses, nonfat salad dressings, snacks (rarely): homemade whole grain cookies or cake (usually only for a birthday celebration), homemade candy for Christmas, nonfat ice cream.

Former highest weight: about 320, but usual average was closer to 300. High BP, High blood glucose (borderline diabetic to diabetic), chronic pain in back, neck, shoulders, knees and feet. I was always HUNGRY.

Do you really have to ask me if I still RESENT (far beyond words can say) the official guidelines that prompted me to eat that way? To eat only low fat and nonfat, high (whole grain) carb, and moderate protein (typically from combination of grains with beans)…decade after decade, in hopes of perfecting that (apparently) noble approach and, thus, somehow, someday becoming healthier and/or slimmer?

I was that “Diet for a Small Planet” teen (enthusiastic and convinced), then I became the young mother who insisted on “whole foods” and home made everything. No butter, no cream, no full fat cheeses of any kind, only the leanest cuts of chicken (or tuna packed in water), etc. No-fat mayo. Olive oil sparingly. I was totally and completely duped and deluded into believing that SOMEDAY the poor health results from that diet would change, if only I perfected fat restriction as an art form.

I’m not saying that others should follow my current example, not saying anyone else would have similar results. I’m just grateful that I took a risk (founded on desperation) and acted contrary to everything I learned about nutrition in nursing school.

I’m really satisfied, now, with food. I eat the fatty things I like the most. I don’t eat for the sake of “health” or “nutrition” but for pleasure and comfort. My appetite fluctuates–sometimes hungry, sometimes not so much. I still bake whole grain bread, muffins, etc, for family members who enjoy them. (I still enjoy baking.) I have no idea if I’m any “healthier” now or not. I have all the same struggles as before—with PTSD and ADHD. At least now, however, I can focus my energy on finding better treatments for those challenges and disabilities. In the past, typically, my mental health disorders took a back seat to all the other physical problems with which I struggled.

Personal stories like mine, I hope, will encourage others to take their own daring risks—towards change—and to move away from (quickly and assertively) the dominant cultural discourses and the “epistemic closure” of the nutrition status quo.

Wow. I could have written most of this reply, word for word, including the resentment. And I met scores of women in clinic who had similar stories. One day I’ll blog about the woman who made such an impression on me, I willed myself through 3 semesters of biochemistry–was she ever P.O.ed.

We’re going to figure out how to get our voices heard. Or die trying. I got nuthin better to do.

It’s gratifying to know someone else understands. Especially about the resentment. Strangely, these days I almost never discuss my dietary habits or weight, at least not as openly as I did here. For one reason, I never want other people to think I’m implying that they should or could try to replicate my own choices and/or changes. A lot of other variables have contributed to the ongoing changes I experience as an individual; menopause came knocking for instance, LOL, and (weird as it may sound) that transformation has been very very good to me in some unexpected ways (and harder for me in other ways). I also had to pull myself out of the rat race for my own survival, and very few people have that “option” (which is hard to think of in that way–as a choice–when it is practically a matter of living or dying…from stress overload…and when the sacrifices in future security are so extreme.) I can’t predict what internal hormonal (etc) changes (upheavals?) will happen if I am pressured or forced (by material needs…survival needs) into jumping back into the fray before I am better prepared. I try not to worry myself (any more than I have to) about that possibility. It’s too scary.

The costs to human health and well-being (and survival) from stress overload (or *simply* from that which is now considered *everyday stress*)—especially for those living with food/shelter/financial insecurities, mental or physical disabilities (not that those 2 aspects can truly be split apart) and major uncertainties about their futures—are inestimable…mostly overlooked, minimized and/or completely discounted by our dominant cultural discourses, including the major health care discourses. The individualist (*triumphant over all odds*) mythologies run deep hereabouts. They run deepest through some of the political/psych-based/religious ideologies you discuss (or gesture toward) in your current post (essay, actually), especially those that frame individual human outcomes as mostly dependent on self reliance, hard work, perseverance and/or so-called personal will power. Or on *faith*. They are missing out on some powerful sources of mutual aid (social support) and solidarity—and human compassion…especially for the most vulnerable humans among us. Very sad realities to face. Thanks again for sharing your outspoken courage. It’s a rare and wonderful thing to witness these days.

Thanks again for the eloquent response. Especially this: “The individualist (*triumphant over all odds*) mythologies run deep hereabouts. They run deepest through some of the political/psych-based/religious ideologies you discuss (or gesture toward) in your current post (essay, actually), especially those that frame individual human outcomes as mostly dependent on self reliance, hard work, perseverance and/or so-called personal will power. Or on *faith*. They are missing out on some powerful sources of mutual aid (social support) and solidarity—and human compassion…especially for the most vulnerable humans among us. Very sad realities to face.”

You nailed this, and what is especially sad to me is that this same individualist strain has taken over food-health issues as well. You’re overweight/unhealthy? Just follow [insert diet plan], and all your worries will disappear. We all know it is not that simple. Yet every single nutrition intervention I’ve ever encountered lays failure at the feet of the individual. Yes, there will always be–as there have always been–people who suffer due to lifestyle choices. They are not, however, 2/3 of the population. As a society, we are responsible for the current health problems we face; as a society, we must find the solutions. All the powers arrayed to maintain the status quo would love for us to blame ourselves and alienate each other–divided we fall. Mutual aid, compassion, and solidarity are not just frou-frou words here. I think they are the only things that will work. My friend, Jim Turner, a lawyer in DC, says the people in the machine are as much victims of the machine as the rest of us. It is something to remember.

For us “formerly Catholic” guys, the metaphor “nunny state” is more resonant.

“nanny” is upper class British or WASPY New England.

But too many of us have memories of “reverend mothers” more reminiscent of Herbert’s “Dune”, than Milton’s “Il Penseroso”.

So, to allay Milton & Herbert, enjoy Mozart’s “amoroso” –

Slainte

My only experience with nuns is the flying kind–but it makes sense & again, beats “mommy state.” Thanks!

Wow, that is good stuff. Will be sharing your comments online.

hopefulandfree’s words are finding their way into my grad school applications these days!

I tell ya something, I am beyond irritated at both the “mommy-state” and “nanny-state” memes.

People who use either phrase have no damn idea what it is to raise children. It’s not a job for wimps. (It’s also not as complicated a job as The Experts like to make it out to be, but the mere fact that we are criticized no matter what we do, day in and day out, is emotionally and mentally exhausting. Quite beyond the problems the little dears generate from day to day themselves.)

Don’t you remember the phrase “wait til your father gets home”? You want to know what the state is? It’s Big Daddy. Doesn’t give a damn about the day to day scut, just swoops in to rescue when things get out of hand and then takes all the credit when the kids turn out well, whether it’s deserved or not. Equates spending money with parenting, too.

I mean if we’re going to use insulting parental metaphors, let’s be accurate.

I love it. Well said. I should know better. It seems like the idea of a mommy-state would be sorta nice, a sweet lady who smells like vanilla and bacon, who always hugs you and says you’re so smart and good-looking, and tells you not to forget your sweater and your glove is under the couch. But I guess the metaphor is more like the psycho mommy you don’t know is crazy until you grow up and notice that everyone else’s mother doesn’t scrub out the fireplace with a toothbrush and isn’t saving boxes of computer punch cards in the attic–just in case. (Sorry, mom, just kidding.)

I was talking about this with my husband–who is a great guy & who is very supportive of me as I don my cape & tights to save the world—the fact that I worked my ass off (it grew back) as a stay-at-home mom & I have nothing that I can point to (except my amazing offspring, but they were going to be amazing anyway) that “counts” out there in the world. I learned a lot, I developed a lot of skills (in addition to stain removal, I am the queen of stain removal), but I can’t put any of them on my CV or resume. Not to steer gender politics back to my favorite subject, but food is at the heart of this.

If I cook a meal in a restaurant for a customer, it counts towards the GDP, I get paid, it goes on my resume, and if I serve the customer myself I might get a thank-you. If I make the same meal for the same person as a homemaker, it’s a different story except for the “if I serve the customer myself I might get a thank-you” part. And I don’t discount the love that gets put in food at home, but I’ve had some meals out that had all kinds of love in them too–and the people who made them were recognized for their efforts in a tangible way.

But if we want to change the health of America, somehow we are going to have to put cooking food at home for the people you love back in its rightful place in our lives. I have NO idea how to do that.

“Equates spending money with parenting”–too funny. We have a running joke in my house, about how my husband cooks. With his wallet. Ba-dum-bum.

I’d change it in the post, but then your brilliant insight would make less sense. That made my day.

LOL! When it’s my husband’s turn to cook, we have Subway.

I fully acknowledge how time-consuming shopping and cooking is, but I do think that part of the resistance to cooking at home is that we’ve come to regard food as entertainment, and have raised the bar a LOT for what we consider a satisfying meal. Back in my Brady Bunch childhood, dinners were something like baked chicken pieces and two different frozen vegetables. Or hot dogs and a can of baked beans. Grilled cheese sandwiches and lettuce salad. Total prep time was about ten minutes.

I don’t know how we can turn back the clock, or stuff the genie back into the bottle, though. People aren’t satisfied with that kind of food anymore. It was a gradual process for me to lose my taste for the over-sauced, over-flavored meals you find in any restaurant, fast-food place, or supermarket pre-made counter. So, I have no idea either.

Excellent point. I really hadn’t thought about it that way because my mom was (and remains, sorry mom) a terrible cook. Having dinner with my friends, I eventually came to realize that the definition of casserole was not “an unidentifiable combination of ingredients–one of which must be peas–that are burnt on the top and cold in the middle.” Southern cooks (i.e. not my mom, a Yankee) take a lot of pride in their cooking (or did when I was a kid), so meals were simple but very well prepared–prep time, most of the day.

I assume that, even then, many women hated being in the kitchen (my mom sure did & expressed her animosity for the task through the food she prepared), but were not under pressure to create both “healthy” and “fabulous” meals at the same time–and the definition of “healthy” was one that made creating a meal a little easier. I look at your childhood dinners & I see high-quality protein and a vegetable (or an attempt at one)–do we need to ask much more out of a meal?–but I also see scary saturated fat, nitrates, more scary saturated fat, etc. Hmmm, take away the scariness of sat fat and prejudice against stuff in cans, along with the pressure to make Celebrity Chef dinners, and what have you got?

Move over paleo, here comes the “Bradylicious” diet, starring fatty meats, processed and otherwise, veggies out of a can or freezer bag, and plenty of cheese and mayonnaise–white bread optional. It’s signature meal will be “pork chops and applesauce.” I’m kinda likin this . . .

Adele, keep having too much fun! Its worth the reading and if those in power ever feel guilty, have them get one the scale first!

Thanks, Bob. We’ll be waiting a long time if we wait for them to feel guilty, although I do wonder sometimes if any of the public health policy folks involved in this debacle think to themselves “holy cow! what have we done?” or if their powers of denial are just so overwhelming that they can’t even consider the possibility.

Another great analysis. Can I just say, I’m a carnivorous Paleo fanatic who, despite some libertarian leanings, always votes socialist, and believes that the state has a role in regulating most things (but a duty to get them right). And who most days cooks “real food” dinners while the wife works.

You might like this: http://nelliebswartimerationing.blogspot.co.nz/2012/11/in-newspaper-and-on-radio.html

If you’re going to live in the past, do it properly!

Quote from Nellie:

Butter rationing was introduced by the New Zealand Government in October 1943.

It was rationed down to 225 grams (8 ounces) per person which is around 16 tablespoons.

This almost halved the average weekly consumption of butter which was around 415 grams per person, that is a whole lot of butter!!!!!

New Zealanders loved their butter and it was used daily and very liberally in practically every New Zealand kitchen around.

So butter rationing meant that many everyday foods and baked goods were affected so other foods were used in butter’s place.

Suet and dripping were the alternatives, not olive oil or margarine as they were not in common use here in New Zealand.

Margarine, until in recent history, needed a prescription from the doctor to be purchased.

Butter was rationed so that plenty could be shipped off overseas, to Britain and even to the USA, for the war effort.

Milk and cheese, however, was not rationed.

Rationing of butter ended in New Zealand in June 1950.

Thanks so much for the link! I’m not sure I got around to offending the Libertarians as much as I could have, but then, those third parties always get the short end of the stick.

It’s the “duty to get them right” part that has us up a creek, yes?

With you 100% about living in the past properly! In many ways, the meat & (yes) potato days of my youth weren’t such a bad thing. We had butter on our white bread and whole milk with our sugary cereal, but eggs were nutritious and meat was good for you–and somehow, we weren’t fat.

As a Libertarian, I want to know who defines what is “right?” You? Me? Michael Bloomberg?

Is it okay for Bloomberg to limit how much soda you can buy at a restaurant or the movies? Is it all right for him to limit the amount of salt a restaurant can put in your food? Is it all right for him to tell you that you can’t donate food to homeless shelters because the city can’t monitor the fat, sodium and sugar content of the donations (he has, if you haven’t heard)? Mayor Bloomberg thinks so, and his constituency is letting him BE a totalitarian idiot. Yes, totalitarian, because where does it stop, and who gets to decide when it’s all gone too far?

This is the problem with government regulation.

Yup, yup & more yups. I know that some folks see this as a political science issue, as in “What form of government best governs?” I see this as an inherent disconnect between science and policy. Science is by its very nature mutable, open-ended, and open to judgment & interpretation. Theories are supposed to be overturned, our past ideas are supposed to be proven wrong, and two different scientists can look at the same observation and come to different conclusions. Policy is just the opposite. We’d be pretty unhappy if policy changed frequently, or if it was open to interpretation more than it already is.

While I’m not opposed to public health policies in principle, I do feel that we’d better be pretty freakin sure we know that what we are creating a policy for or against is actually a health issue our policy can do something about, and we’d better have some fairly practically-non-mutable, nearly-closed, unanimous science on our side when we do. For nutrition policies directed at the prevention of chronic disease (as opposed to diseases of deficiency), we don’t have anything like that, not even close, no, not even for transfats–although I am happy to have them out of the food system.

But transfats are a great case in point: How did they get into our food supply? Food manufacturers put them in there as a substitute for saturated fats–which government policies were telling us to avoid. When evidence began to emerge that these kinds of fatty acids were associated with negative health outcomes (the evidence is there, but it isn’t as cataclysmic as one would think), it was no big deal for the government to say “avoid transfats.” Why? Because it was no skin off anybody bottom line to do so. A few reformulations here & there & WA-LA, now we can advertise our food as “ZERO transfats!” What $ might have been lost in reformulation would more than compensated for in the $ that comes with a new health-type claim. (I’m afraid Hostess may have been the only food manufacturer not to survive the switch. Hohos just never tasted the same . . . )

“…the idea that the solution to our obesity crisis lies in someone in each American household willingly taking up the mind-numbingly repetitive and eternally thankless chore of putting ‘real food’ on the table for the folks at home 1 or more times a day for years on end—well, it’s as much a fantasy as Karl Rove’s Ohio outcome.”

I’m sorry, but as the person who HAS performed this “mind-numbingly repetitive and eternally thankless chore” for 30 years while working a full-time job (often 60 to 80 hours a week), I call bullshit on this. It CAN – and should – be done. It simply needs to be made a priority, and it is certainly a “chore” that can be shared by more than one member of the family. It’s not that hard to make time for it, either – providing your family with food that nourishes them, rather than merely feeds them, is certainly more important, or should be, than who was kicked off Dancing With The Stars or American Idol. Pick one.

I agree with you on the importance of the task, but I’m afraid we may be in the minority, not just in terms of prioritization, but know-how and willingness to shoulder the primary responsibility for the task. A lot of my younger classmates in the MPH/RD program see lots of value in cooking–in restaurants as chefs or in classes as nutritionists. The ones who were interested in doing it at home for a family, not so many. You’re right it is a chore that needs to be done, but sometimes it ranks right up there with cleaning the toilet bowl–and garners just about as much admiration out there in the world.

I did it for 20 years before going back to school (I drew the line at trying to learn organic chemistry, working & being in charge of dinner all at the same time–so I heartily applaud your stamina for the job). I didn’t miss it & I actually LIKE cooking, just not planning, shopping, managing inventory, etc. One thing I know for sure, though, is that–much to my surprise–reduced carb cooking is actually less of a chore than the low-fat vegetarian meals I used to make.

We’ve used nutrition to create a false dichotomy between homemade “healthy” meals of (arsenic-laced) brown rice and lentils vs. KFC/Taco Bell. (Yes, I know there are 30-minute low-fat meals out there, I have the cookbook, but the cheap “nutritious” foods are in competition with cheap fast food, not carefully planned, shopped for & cooked “nutritious” foods.) It might help if we made frying a pork chop or a couple of eggs for dinner (hard to get easier than that) an okay thing to do. It might help if we made nutrition & cooking part of the school curriculum again. It might help if we knew what “real” food was and what it was supposed to taste like.

But it doesn’t help to tell people to “just eat real food” without creating some support that allows that to happen: social approval, knowledge, skills–shoot, maybe a reasonable agreed-upon definition for what “real” food is?

I have to agree with you. I have no love for the cooking process but deep respect for the importance of nutrition: I can have something prepared faster than someone can drive down the street to order a fast food meal and return. People make things harder than they have to be. For grain eaters, a traditional oatmeal recipe would have been to soak the oats over night in (raw) milk, perhaps with honey stirred in. No cooking required — I got that recipe as a passing reference from Juliette Bairacly Levy in an herbal book. Eggs fried in coconut oil? 5 minutes. Walking into the backyard to cut greens? 5 minutes. Yogurt? 1 minute.

I appreciate the simplicity you illustrate here, and I do think people make things harder than they have to be. But all of those things require thinking ahead (planting greens, overnight soaking, the presence of eggs in the house!). Your reply reflects deeper objectives, those of slowing down just a little, having time to think and plan (and plant), making a priority of what really matters, as Janis mentioned. For some of us, it’s a no-brainer: decent food or one more meeting/accomplishment/dollar. For others of us, we don’t even know what we’re missing. As things stand now, it’s tricky to try to suggest that fried eggs make an okay quick meal because 1) “eggs are as bad as smoking,” right? and 2) people literally don’t know how to fry an egg (no joke, I had to bring a frying pan to clinic to show people what one looked like). So–we have a lot of ground to cover.

Ultimately, I think it’s all connected to the ideas that hopefulandfree brings up. How do we restore compassion–for ourselves, each other? I do think food is part of the answer. You can get a lot of love into food. Past that, I don’t know.

yet another great article! thanks, Adele!

Thanks! I’m just having too much fun : )