The blogsphere is beginning to rattle with commentary on the recent Ancestral Health Symposium 2012 events. Some folks who don’t necessarily “look the paleo part” have voiced concern about feeling excluded or marginalized as the conversation/social activities/celebrity parade seemed dominated by:

- white people

- young people

- thin/athletic/fit people

- men

- well-educated, upper-middle class socioeconomic status people

- people wearing goofy-looking shoes

You can read my take on why that might be the case here: AHS 2012 and the BIG BUTT: Lessons in Nutritional Literacy.

I understand that an NPR reporter was at the event, interviewing some of the movers and shakers. There was some concern that the reporter seemed to think that the paleo movement is a bit of an elitist fad. I understand this perspective, and on many levels, I agree.

As a “fad,” the paleo movement is a bunch of highly enthusiastic people with a lot of disposable income and time who are deeply committed to a particular way of being fit and healthy. It has its leaders, it controversies, its “passwords” (can you say “coconut oil” or “adrenal burnout”?), and its stereotypical paleo dude or dudette. As a fad, it would be destined to go the way of all of other diet and health fads—including Ornish and Atkins, Pritikin and Scarsdale, extending all the way back to the “Physical Culture” movement of the earlier part of this century (Hamilton Stapell spoke about this at AHS2012).

The original paleo chick – no high heels on this lady

Is it elitist? Well, there are some ways that it is possible that the paleo movement may marginalize the very folks who might benefit most from its efforts. Maybe an African-American guy still sensitive to the fact that his grandfather was consider “primitive” might not want to get his full cavemen on. Maybe a Mexican-American woman who remembers her abuela telling her stories about being too poor to have shoes doesn’t really want to go back to being barefoot just yet. Maybe an older, heavier person simply feels intimidated by all the young healthy fit people swarming to the front of the food line.

But the paleo movement does not have to be an elitist fad unless insists on limiting itself to its current form, and I believe the people at the Ancestral Health Society are working hard to make sure that doesn’t happen. This is why I really love these folks. I don’t mean the paleo leaders like Mark Sisson or Robb Wolf, although I’m sure they’re good people; I’ve just only met them briefly. I mean those somewhat geeky-looking-in-an-adorable-sort-of-way folks in the brown T-shirts who hung in the background and made it all happen for us last week. Notice that they don’t call themselves the Paleo Health Society, right? I love them because they ask good questions, they question themselves, they think long-term, and they’ve created a community that allows these conversations to take place.

So, what do we do to transform this paleo-led, AHS-supported community into the public health, human rights revolution it could be?

According to Doug Imig at the University of Memphis, a protest becomes a movement when:

1) It defines and proclaims widely shared cultural norms.

2) It creates dense social networks.

3) It gives everybody something to do.

Each of these deserves its own blog post, so let’s look at the first—and most important—item: widely shared cultural norms. This is where the “elitist fad” part of paleo falls short, but not really. Because in all my encounters with paleo folks and people from AHS, I find norms and values that the culture as a whole can embrace. Here’s the weird thing, I’ve spend the past couple of years also talking to mainstream scientists, from one end of the diet spectrum to another, including Joanne Slavin, a down-to-earth, warm, wonderful lady who was on the most recent Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee and Henry Blackburn, who is a delightful gentleman and a protégé of Ancel Keys. Guess what? We all have some values in common.

Here are some concepts that I think may unite us all, from vegan to primal, from slow food to open government, from “mainstream” scientist to “fringe scientists” like Gary Taubes (yes, one of my UNC instructors referred to GT as a “fringe scientist,” although another found his views “very convincing”—go figure):

We must create an open, transparent, and sustainable food-health system.

The RD that inspired me to take an internship at the American Dietetic Association for a semester, Mary Pat Raimondi, said: “We need a food system to match our health system.” And whatever shape either of those systems may take, she is absolutely right. Conversations about food must encompass health; conversations about health must encompass food.

Right now our food-health system is closed. Directives come from the top down, public participation is limited to commentary. The people who are most affected by our nutrition policies are the farthest removed from their creation. We need to change that.

Right now our food-health system lacks transparency. USDA and HHS create nutrition policy behind doors that only seem to be transparent. Healthy Nation Coalition spent a year filing Freedom of Information Acts in order to get the USDA to reveal the name of a previously-anonymous “Independent Scientific Panel” whose task, at least as it was recognized in the Acknowledgments of the Dietary Guidelines, was to peer-review “the recommendations of the document to ensure they were based on a preponderance of scientific evidence.” You can read more about this here, but the reality is that this panel appears to not be a number of the things it is said to be. This is not their fault (i.e. the members of the panel), but an artifact of a system that has no checks and balances, no system of evaluation, and answers to no outside standards of process or product. This must change.

Our food-health system must be sustainable. And Pete Ballerstedt would say, yes, Adele, but what do you mean by “sustainable”? And to that I say—I mean it all:

Environmental sustainability – Nobody wants dead zones in the Gulf or hog lagoons poisoning the air. But environmental sustainability can’t be approached from the perspective of just one nutritional paradigm, because a food-health system must also have:

Cultural sustainability – We are not all going to become vegans or paleo eaters. Our food-health system must support a diversity of dietary approaches in ways that meet other criteria of sustainability.

Economic sustainability – Our food-health system must recognize the realities of both producers and consumers and address the economic engines that make our food-health system go around.

Political and scientific sustainability – Our food-health system must become a policy dialogue and a scientific dialogue. Think of how civil rights evolved: an equal rights law was passed, then overturned, a Jim Crow law was passed, then overturned, an equal right law was passed, then upheld, etc. etc. This dialogue reflected changing social norms and resistance to those changes. But we have no way to have a similar sort dialogue in our food-health system.

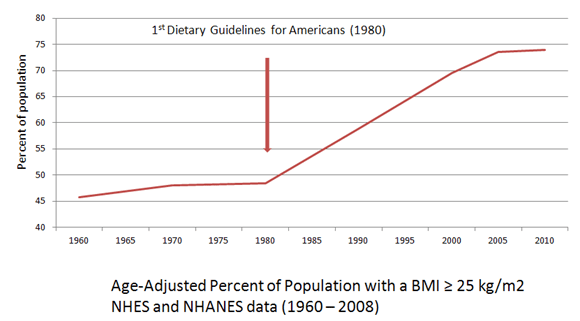

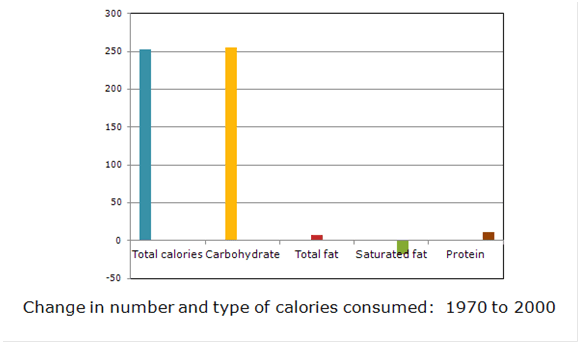

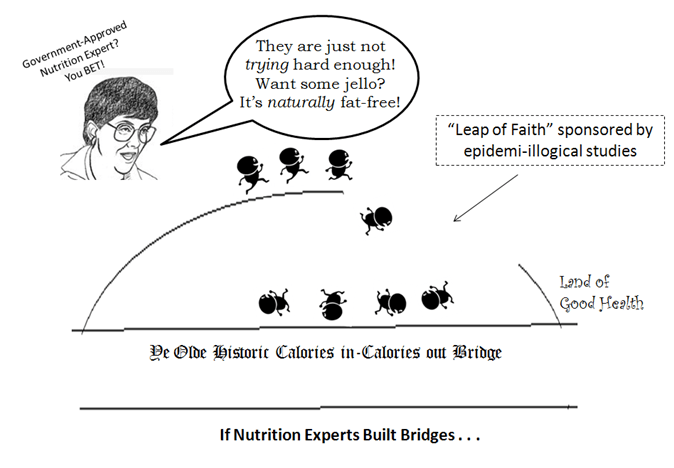

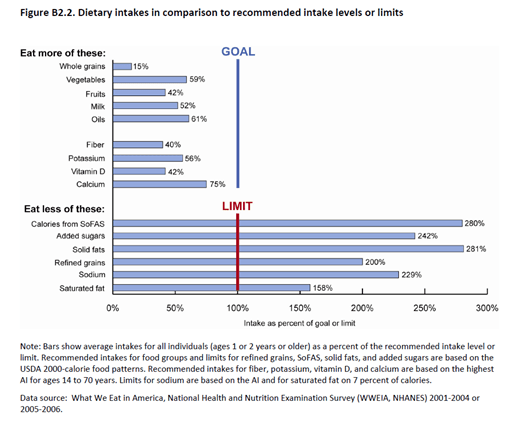

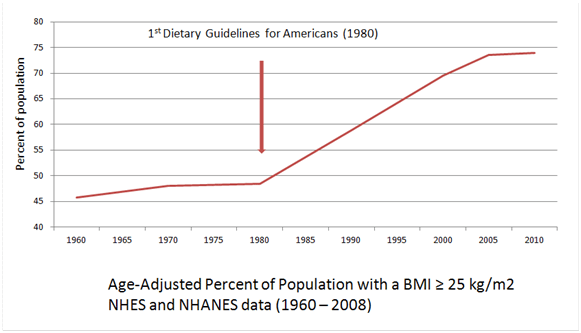

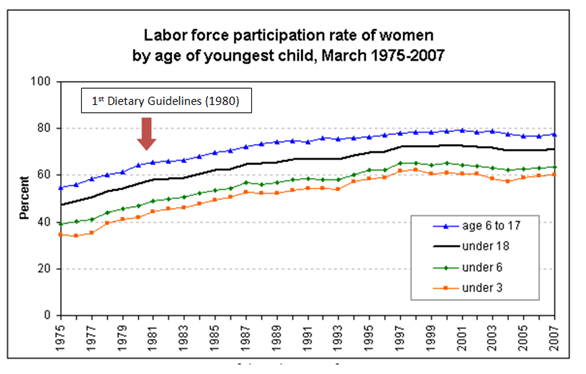

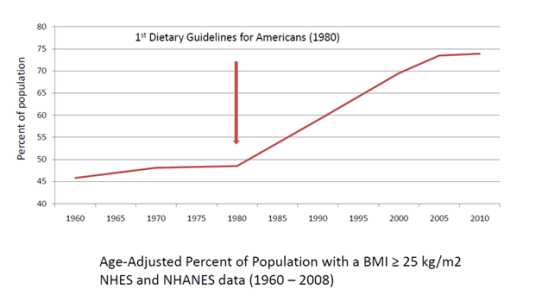

What would the world look like if, in 1980, an imaginary Department of Technology was given oversight of the development of all knowledge and production associated with technology? Production of food and knowledge about food (i.e. nutrition) became centralized within the USDA/HHS in 1977-1980 and there have been no policy levers built into the system to continue the conversation, as it were, since then. The Dietary Guidelines have remained virtually unchanged since 1977; our underlying assumptions about nutrition science have remained virtually unchanged since 1977. That’s like being stuck in the age of microwaves the size of Volkswagens, mainframe computers with punchcards, and “Pong.” We need a way for our food-health system to reflect changing social and scientific norms.

One of the primary shifts in understanding that has taken hold since 1977 is that:

There is no one-size-fits-all diet that works for everyone.

In 1979, Dr. William Weil Jr at the Department of Human Development at Michigan State University, voiced concern about “the frequent use of cross-national and cross-ethnic inferences” [Weil WB Jr. National dietary goals. Are they justified at this time? Am J Dis Child. 1979 Apr;133(4):368-70.] He went on to day that we cannot assume that “because ‘a’ and ‘b’ are correlated in one population group that they will also be correlated in another group” yet our one-size-fits-all dietary recommendations make just that assumption.

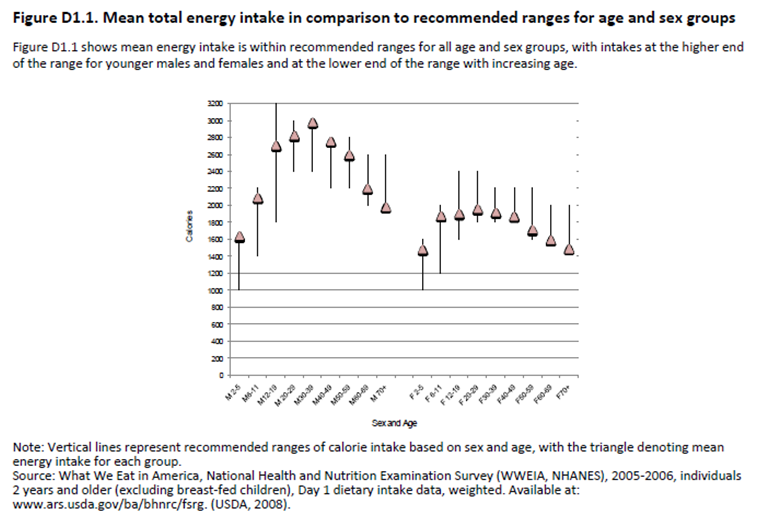

There were more scientific articles generated from the Nurses’ Health Study–composed of 97% white women–in 2009 alone, than in the entire 10+ year history of the Black Women’s Health Study. Those large epidemiological studies done with a mostly white dataset are what drive our policy making, even though evidence also points to fact that we should not be making the assumptions to which Dr. Weil referred. A landmark study published in 2010 shows that African-Americans who consumed a “healthier” diet according to Dietary Guidelines standards actually gained more weight over time than African-Americans who ate a “less healthy” diet [Zamora D, Gordon-Larsen P, Jacobs DR Jr, Popkin BM. Diet quality and weight gain among black and white young adults: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study (1985-2005). American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010 Oct;92(4):784-93].

.

DQI stands for Diet Quality Index. Blacks with a higher DQI had more weight gain over time than blacks with a lower DQI. From Zamora et al.

Even with a more homogenous population, this issue applies. Remember all those discussions about “safe starches” you heard at AHS2012?

This concept also captures the emerging knowledge of how genetic variability affects nutrition needs and health, i.e. individualized nutrition, a very useful buzzword. I have lots to say about n of 1 nutrition coming up soon. But, most of all, not trying to cram everyone into the same nutritional paradigm captures reality of our own lives and choices about food. Which brings me to:

Food is not just about nutrition, and nutrition is not just about science.*

When we all begin to question our own assumptions about food and nutrition, we will be better able to reach across communities, create common ground, and be humble about our way forward.

We need to understand and help others understand that all nutrition messages are constructed and contain embedded values and points of view.

We need to learn to ask and teach others to ask: Who made the message and why? Who may benefit or be harmed? How might people interpret this message differently?

We need to think and help others to think about income and funding models, industry, and the framing of dietary problems by scientist, bloggers, and the media (and I don’t just mean “the other guys”—apply these critical thinking skills to your own nutrition/food community).

Nothing about our food and nutrition thinking was born in a vacuum. Food is a part of our cultural and social fabric. It allows us to belong; it allows us to define ourselves. Even as we strive to find better science and to shift our current diet-nutrition paradigm, we must approach this with the understanding that there is no truly objective science. How science gets used, especially in the policy arena moves us even farther from that non-existent ideal. Even as we strive to improve public health, we must understand that we don’t always know what “health” and “healthy food” means to the people we think we are trying to serve.

If these points sound remarkably like the mission statement for Healthy Nation Coalition, my non-profit, then you’ve been paying attention. But it is not my plan for HNC to “lead” any nutrition reform movement as much as it is for us to get behind everyone else and shove them in the same direction. There is very much a herding kittens aspect to this (as Jorge of VidaPaleo.com pointed out), but as a former high school teacher and mother of three, this is not new territory to me.

So, yes, I have an agenda. Everyone has an agenda. I’ll spell mine out for you:

Somewhere out there in America, today, there is a young African-American girl being born into a country where many—if not most—of the forces in her world will propel her towards a future where she will gain weight, get sick, have both of her legs amputated, get dialysis three times a week, be unemployed and unemployable, on disability and welfare, and—this is what gets me out of bed in the morning and drags my weary ass to one more round of getting punched in the face by those very forces arrayed against her—she will, somewhere underneath it all, blame herself for her situation. I’m an old white lady, in a position of relative power and knowledge. I don’t know this young lady, and she doesn’t know me. She doesn’t owe me anything because she’s not asking for my help. But it is my job in this life to begin—at the very least—to shift those forces so that she has a better opportunity to choose a different life if she wants to. That’s all I care about. I don’t care who gets credit or who gets the cushy book deal. I just want it to happen. I would want the world to do the same for my children if they had not had the privilege of birthright that they do. That child is my child as sure as the three that live here and drive me crazy are. All I ask of the paleo community is that she be your child too. And if, as a community, you decide to adopt this child, well then, don’t worry about becoming an elitist fad made up of goofy-shoe wearing white people destined to fade into obscurity. Instead, you all will change the world.

Next Up: What makes a movement? (and I mean a social change one, not the bowel-y kind)

*Much of what follows borrows liberally from the work of Charlotte Biltekoff at UC-Davis, a wonderfully warm and intelligent woman who has been working on and thinking about this issue for—believe it or not—longer than Gary Taubes. She has a book coming out next summer which, IMHO, will be the social/cultural partner to Good Calories, Bad Calories.