The 2015[6] Dietary Guidelines are out today. Although restrictions on cholesterol and overall fat [read: oil] content of the diet have been lifted [sorta, not really], the nutrition Needle of Progress has hardly budged, with saturated fat and sodium still lumped into the same “DANGER Will Robinson” category as trans fats and added sugars–and with cholesterol still carrying the caveat that “individuals should eat as little dietary cholesterol as possible.” The recommended “healthy eating pattern” calls for fat-free/low-fat dairy, lean meat, and plenty of whole grains, plus OIL. In other words, the diet is still low-fat and high-carb–just add vegetable oil [you know, locally sourced, whole-food canola, corn, and soy oil].

However, the most disturbing part of the Guidelines is Chapter 3, which heralds “a new paradigm in which healthy lifestyle choices at home, school, work, and in the community are easy, accessible, affordable, and normative.” In other words, let’s make what we’ve determined is the healthy choice, the easy–and morally permitted–choice for everyone [read: especially for those minority and low-income populations who insist on eating stuff we disapprove of].

Thus, it seems appropriate that today’s featured post focuses less on nutrition and more on the cultural context in which nutrition happens. Without further ado:

Low Fat, High Maintenance: How money buys lean and healthy–plus, an alternative path to both

Guest post by Jennifer Calihan at eatthebutter.org

It’s Friday evening. There is a chill in the air. The smell of ‘Walking Tacos’[i] wafts over from the row below. A rousing, “Give me an ‘S’!” commands my attention. All the cues point to one thing – I am sitting at another high school football game. I’m not really a huge football fan, but my son plays on the team, and I love watching him.

The parents and fans from my son’s school all sit on one side of the field, so the stands are filled with friends and many warm, familiar faces. I am struck, as I always am, by how good everyone looks. I see a lot of grey hair on the men but not much on the women – funny how that works! The adults watching are at least 40, and some are probably mid-fifties. But what is truly striking about this crowd is how trim they all are. Are there some people struggling with their weight? Sure. But the majority of these folks are maintaining a normal weight. No sign of the obesity epidemic on this side of the field. And I wonder what I always wonder – how do they do it – really?

At half time, I take a walk over to the visitor side of the field to stretch my legs. Over here, the stands tell a different story. The parents and fans of the visiting team look… well, they look like most American crowds. Although this crowd seems a little younger than the home team fans, most of the people here are struggling with their weight. In fact, our national averages would predict about 68% of these adults are too heavy; 38% would be obese, plus about another 30% overweight. And, based on what I see, that sounds about right. But it is not the weight, per se, that worries me. It is the metabolic disease that often travels with excess weight that is cause for concern. Diabetes, heart disease, fatty liver… a future of pills and declining health.

Experts acknowledge that obesity and the diseases that travel with it are tied to income. Simplistically, you might think something like, “more money = more food = more obesity,” but that is just not how it works. As most of you know, it is the reverse. “Less money = more obesity.” So it may not surprise you to hear that my son attends an independent school in an affluent area. And the visiting team is from a less affluent suburb. So, the mystery is solved – skinny rich people on one side, and overweight middle-class people on the other.

What interests me is the, ‘How?’ As in, ‘How do the skinny rich people do it?’

I affectionately refer to my neighborhood, and others like it, as ‘the bubble.’ The bubble is safe… it is comfortable… it is beautiful. But how, exactly, does the bubble protect my family and my neighbors from the obesity epidemic? Just as it is not a happy accident that actresses age amazingly well, it is not a happy accident that the affluent stay lean. Most of them spend a lot of time and money on it. They have to. Our nation’s high-maintenance dietary recommendations require most eaters to invest a great deal of resources to combat the risk of obesity and diabetes that is built into low-fat eating. Unfortunately, this means middle-income and working class families, who may be lacking the resources to perform this maintenance, are launched on a path toward overweight and diabetes. What can be done to level the playing field?

Seven Ways Money Buys Thin

1. More Money Buys Better Food

For many in the bubble, there is not a defined budget for groceries. And, let’s face it, that makes shopping successfully for healthy food – however you define it – just a tad easier. To imagine the flexibility that wealth can afford, consider this inner dialog that happens in a Whole Foods aisle near you. In the bubble, a mom might consider: “Should I buy the wild salmon or the chicken tenders for dinner? Hmmm… let’s see here. $28.50 or $8.99? My, that is quite a price difference. But those tenders are pretty processed. And they aren’t gluten-free. I’ll go with the salmon this week – Johnny loves it, and it’s so healthy.” If it doesn’t really matter if the food bill is $300 or $350 this week, why not buy the wild salmon?

Much has been written about how cheap the processed calories in products like soda and potato chips are, and how tempting those cheap calories are to people who are shopping, at least on some level, for the cheapest calorie. I find it hard to believe that any thinking mother is buying soda because it is a cheap way to feed her family. My guess is that she is buying soda for other reasons: habit, caffeine, sweet treat, etc. But certainly, refined carbohydrates and refined oils, which I believe are uniquely fattening, are cheap and convenient and are often processed into something remarkably tasty. So yes, I think small grocery budgets lead to more processed foods and more fattening choices.

Higher grocery budgets often lead to high-end grocery stores that offer exotic, ‘healthy’ products, which, on the margin, may be healthier than their conventional counterparts. Quinoa pasta, hemp seed oil mayonnaise (affectionately known as ‘hippie butter’), cereals or crackers made from ancient grains, and anything made with chia seeds all come to mind. Last week, I saw Punkin Cranberry Tortilla Chips on an endcap. Seriously? (Yet, mmmm… how inventive and seasonal!) The prices are ridiculous, but upscale shoppers snap up these small-batch, artisanal products, regardless. They may not be worth the money, and may not really taste all that good, but they carry an aura of health and make you feel really good about yourself when you put them in your cart.

Higher grocery budgets often lead to high-end grocery stores that offer exotic, ‘healthy’ products, which, on the margin, may be healthier than their conventional counterparts. Quinoa pasta, hemp seed oil mayonnaise (affectionately known as ‘hippie butter’), cereals or crackers made from ancient grains, and anything made with chia seeds all come to mind. Last week, I saw Punkin Cranberry Tortilla Chips on an endcap. Seriously? (Yet, mmmm… how inventive and seasonal!) The prices are ridiculous, but upscale shoppers snap up these small-batch, artisanal products, regardless. They may not be worth the money, and may not really taste all that good, but they carry an aura of health and make you feel really good about yourself when you put them in your cart.

The idea that money buys better food also rings true when eating out. The cheapest restaurants tend to offer more processed calories with fewer whole food choices. And, even on the same menu, the fresh, whole foods tend to be quite expensive, especially if you look at cost per calorie. Again, in the bubble, a mom might consider, “Pizza tonight? Or should we stop by Cornerstone, the local home-style restaurant, and get grilled chicken with broccoli and a salad? Hmmm… $20 or $60? Well, we did pizza last week; I think we should go to Cornerstone.”

The bottom line is that money can buy more choices and some of those choices are less likely to add pounds.

2. More Money Buys More Time to Cook and/or More Shortcuts

Most of the moms (and a rare dad or two) in my circles have time to shop and cook because they are not working full-time. Thus, higher family income can mean more home-cooked meals. Cooking at home gives families more control of ingredients and portions. It also tends to mean more whole food and less processed food, which most agree is better for weight control.

Of course, affluent working moms are the exception to this, as they have little time for grocery shopping and cooking. But, again, money can help here. Many of my friends who work full-time outsource the grocery shopping and/or cooking to a nanny, a housekeeper, or a personal chef service. Even in a mid-sized city like Pittsburgh, there are boutique, foodie storefronts that deliver healthy, home-made meals for $12-16 (each). Lately, some moms are using the on-line services (like Blue Apron, Hello Fresh, Plated, and even The Purple Carrot, which offers a vegan menu) that ship a simple recipe and the exact fresh ingredients needed to make it to a subscriber’s door each day. How convenient! For only $35 or $40, you can feed your family of four AND still get to cook dinner. Perfect. Many skip the whole experience and simply purchase fully cooked gourmet meals at high-end grocery stores, which tend to run $8-15 per person. Fabulous. What a nice option for the health-minded busy mom who is not on a budget. Of course, not all working mothers are quite so lucky.

3. More Money Buys More Time to Exercise And More Access To Exercise

I am a firm believer that one cannot exercise one’s way out of a diet full of nutritionally empty calories. BUT, if people get their diet headed in a decent direction, daily exercise can really help them cheat their way to thin even if they are still not eating right all of the time. So, exercise is certainly a factor in this puzzle, particularly for people eating low-fat diets that seem to require a steady, daily burn of calories. As a committed non-athlete, I am continually amazed by how much my friends exercise. Running, walking, biking, swimming, tennis, squash, paddle tennis – the list goes on and on. Now, small fitness facilities offer pricey, specialized workouts: lifting, yoga, Pilates, rowing, bootcamp, kick-boxing, TRX, Pure Barre, spinning, Crossfit, and the very latest – wait for it – OrangeTheory. These boutique fitness plays are becoming more common, and can run up to $500/month… not kidding. Here’s more on this trend from the WSJ.

Whew. It is exhausting to even imagine keeping up with most of my friends and neighbors. But I give it a go… sort of. Devoting an hour or more each day to exercise is much easier for those living in the bubble. Let’s be honest – people with money can afford to outsource some of the busywork of life. If you don’t like cleaning your house or mowing your lawn or weeding the flowerbeds or repainting the fence or doing laundry, don’t do it. Pay someone else to do those things, so you have time for spinning 3x a week plus Pilates (work that core) and tennis. Have baby weight to lose? No problem. Hire a babysitter and a trainer and you will make progress.

Good trainers, although expensive, often deliver more effective exercise, more efficient routines, more entertaining workouts, and better results. Appointments are scheduled and you pay whether you go or not, which makes showing up more likely. You can even find a buff guy who will yell at you if you find that motivating. Personal trainers are just one more way money buys thin.

When I think back to what my mother might have considered doing to stay fit when she was my age, I come up with one thing and one thing only: walking the golf course. And I lived up north, so the golf season was only 18 weeks long. She had no regular workout routine, nor did any of her friends. Did she have cut arms, toned abs, and look great in a bikini? Absolutely not. Was she overweight? Absolutely not. And she had the good sense not to wear a bikini, btw. It’s amazing that she could maintain her weight without regularly scheduled exercise. Her game plan was old-fashioned: bacon and eggs fried in butter for breakfast, no starch at dinner, very occasional desserts, plus a couple very dry martinis, never before 6pm. She’s a size 10 at age 91, so I’d say it worked for her.

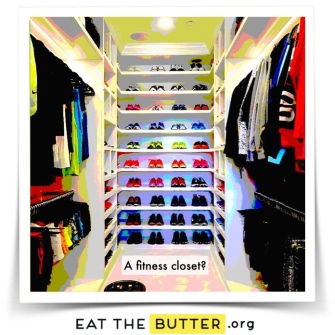

Ti mes have changed. In the bubble, 50-year-old upper arms are proudly bared, even in winter, and women walking around in fitness gear is so commonplace that the industry has a term for this fashion trend: athleisure. If you think I might be making that up, check out this WSJ article, “Are You Going to the Gym or Do You Just Dress That Way?” The fact that Nike’s sales of women’s products topped $5 billion in 2014 is a little startling, no? Some women even need a completely separate closet to house all of their Nike apparel. Khloe Kardashian claims her fitness closet is her favorite closet. Ummm… not quite sure what to say about this, except that girl has a lot of sneakers.

mes have changed. In the bubble, 50-year-old upper arms are proudly bared, even in winter, and women walking around in fitness gear is so commonplace that the industry has a term for this fashion trend: athleisure. If you think I might be making that up, check out this WSJ article, “Are You Going to the Gym or Do You Just Dress That Way?” The fact that Nike’s sales of women’s products topped $5 billion in 2014 is a little startling, no? Some women even need a completely separate closet to house all of their Nike apparel. Khloe Kardashian claims her fitness closet is her favorite closet. Ummm… not quite sure what to say about this, except that girl has a lot of sneakers.

One doesn’t have to be athletic to exercise, so I am guilty of some of this behavior (although I swear I only have one drawer for my fitness gear). I am sure there are some naturally thin couch potatoes among the parents of the students enrolled at my son’s school, but they are the exception. Most of the lean and affluent are working pretty hard to look the way they look.

4. More Money Buys Access to Better Ideas About What Makes You Overweight

Maybe it is your personal trainer who talks to you about trying a Paleo diet. Or, perhaps your trip to Canyon Ranch exposes you to a more whole food, plant-based, healthy fats approach to eating. Or, if you prefer to ‘spa’ at Miraval, you might learn about Andrew Weil’s anti-inflammatory food pyramid. Maybe your friend recommends an appointment with a naturopathic MD who suggests that you try giving up grains. The point is, if you have money, you have a greater chance of hearing something other than ‘eat less, exercise more’ when you complain about your expanding waistline. The affluent have easy access to many different ideas about diet and health, so they can experiment with several and see which one works for them.

Today, one of the most popular alternative ways of eating is a plant-based, ultra-low-fat diet. Books and sites (like the in-your-face, aptly named Skinny Bitch brand) market snotty versions of this blueprint for weight loss to their upscale customers. I see many women in my circles eating this near vegan diet these days: lots of whole vegetables and grains, very little fat, with perhaps a little lean meat, fish or eggs occasionally. Although this is not my chosen approach, as it requires giving up too many of my favorite foods and leaves me perpetually hungry, it seems to deliver some pretty skinny results. And, since it is in vogue, it is something that will be accommodated at parties in the bubble – plenty of crudité platters with hummus and beautiful roasted beet salads, sprinkled with pumpkin seeds, pomegranate kernels, and just a touch of olive oil. In affluent communities, being among friends and acquaintances who practice an alternative approach to eating means social activities are “safe” places to eat, not minefields of temptation. I don’t mean to suggest that people in less affluent suburbs have not heard of a vegan diet or only socialize around piles of nachos; I would maintain that those communities are as invested in their health as affluent ones. But, if your social circle has access to better food, as well as better information about food, you are more likely to be a part of a “culture of skinny.”

5. More Money Buys a ‘Culture of Skinny’

Living in the bubble means living among the lean. Which, as you might imagine, increases the odds that you will be one of them. There is a lot of peer pressure to look a certain way, and being surrounded by people who look that way certainly gets your attention. It also gives you hope that being thin is a reasonable expectation – as in, “If all my neighbors have figured it out, so can I.” And, it helps that there will be healthier food at most gatherings. When the trays of cookies do come out, none of your friends will be reaching for more than one, either. So the bubble is sort of a support group for staying lean. As the success of AA can attest, when it comes to habits and willpower, support groups matter.

There is even some research to back this up. Did you know that you are 40% more likely to become obese if you have a sibling who becomes obese, but 57% more likely to become obese if you have friend who becomes obese?[ii] It’s a little weird to think of obesity as socially contagious, but it seems that social environment trumps genetics. An article in Time explains it this way: “Socializing with overweight people can change what we perceive as the norm; it raises our tolerance for obesity both in others and in ourselves.”[iii] (Emphasis mine.)

There is even some research to back this up. Did you know that you are 40% more likely to become obese if you have a sibling who becomes obese, but 57% more likely to become obese if you have friend who becomes obese?[ii] It’s a little weird to think of obesity as socially contagious, but it seems that social environment trumps genetics. An article in Time explains it this way: “Socializing with overweight people can change what we perceive as the norm; it raises our tolerance for obesity both in others and in ourselves.”[iii] (Emphasis mine.)

Living immersed in the ‘culture of skinny’ makes the sacrifices you must make to stay that way more bearable. Misery loves company, and I often think that eating way too much kale and being hungry all the time is easier if you are doing it with friends… Odd to think of widespread hunger in the affluent suburbs, I know, but I think there is a fair amount of self-imposed hunger here. Likewise, on the exercise front, you certainly won’t lack company on the paddle court or walking paths, and exercising with friends can truly be fun. Plus, you can take solace in the fact that you won’t be the only one foregoing the pleasure of lying on the couch with a glass of Chardonnay watching Downton Abby in order to make it to your spin class. In the bubble, the penalty for not keeping up with your diet and exercise regime is higher. Being the only obese mom or dad standing on the sidelines at Saturday’s soccer game can feel a bit isolating. The ‘culture of skinny’ cuts both ways – it can serve as both a carrot and a stick.

6. More Money Buys Other Ways to Treat Yourself (and the Kids)

I attended a workshop about obesity and food deserts a couple of years ago. It was sponsored by a group of venture philanthropists (think: savvy business people advising and funding fledgling non-profits), hoping to shed some light on the obesity epidemic. One of our assignments was to go into a small market in a blighted urban neighborhood and try to buy food for a few meals for a single mother and two young children. Of course, the earnest healthy eaters (self-included) in our group dominated, and we came back with things like whole milk, regular oatmeal, vegetable soup, and turkey deli meat. Boy, were we – visitors to this world – going to prove that even in a food desert and on a budget, healthy eating was possible if we made wise choices. When we returned for the debrief, another mother said, “You know, we bought all this healthy stuff, but if I were that single mother, wouldn’t I want to bring home some joy? Like, something that would make my kids smile?” And, of course, she was right. If money were tight, would I really buy unsweetened oatmeal, disappoint my kids, and listen to the subsequent really loud whining? Probably not. I think I would bring home Captain Crunch and see some joy.

In the bubble, breakfast does not have to be a treat. Like all mothers, I have to pick my battles, but breakfast can be one of mine. Would I be as likely to refuse to buy sweetened cereal if there were more important battles to fight? No. And, for the adults, maybe the food-reward cycle becomes less important when there are so many other ‘treats’ coming… the manicure, the tennis lesson, the new jeans… whatever it is that makes food less important.

7. More Money Buys Bariatric Surgery

If all else fails, people with resources have a surgical option. This is, of course, a very invasive approach to the problem – surgically altering the human anatomy to suit the modern diet rather than altering the modern diet to suit the human anatomy. But type 2 diabetes remission rates as high as 66% have been reported (two years post-op)[iv], so bariatric procedures offer more than just a cosmetic result. Our health care providers love this option. (How exciting: a new profit center!) Expensive bariatric procedures are actually available outside the bubble because insurance will cover most of the costs. How interesting that this somewhat extreme solution is the tool that is subsidized enough to bring it within reach of our middle class citizens. But, of course, those without the means to fund the deductibles, out-of-pocket costs, and time off work cannot afford even this option.

Another Inconvenient Truth

Here’s the thing. As a nation, we have (perhaps inadvertently) chosen to push, EXCLUSIVELY, a very high-maintenance diet. (And I know high-maintenance when I see it.) A diet that requires most of its eaters to either perform hours of exercise each week, or endure daily hunger, or both, in order to avoid weight gain and/or diabetes. A diet that has taken us down the tedious path of measuring portions, counting calories, and wearing Fitbits. This is far from ideal, and has left too many of us hungry, tired, crabby, and sick, not to mention pacing around our homes at night in our daily pursuit of 10,000 steps. Yes, there are those genetically gifted people who can eat low-fat, not be chained to a treadmill, and remain skinny – ignore this irrelevant minority. Yes, there are neighborhoods of affluent people where most seem to make it work – ignore them, too. We should not let the success we see in privileged communities give us hope that our current low-fat dietary paradigm is workable. The bubble is a red herring; it telegraphs false hope.

Our nation’s overall results speak for themselves. Low-fat diet advice will never work for most Americans. Never-ever. Sticking, stubbornly, to our high-maintenance food paradigm is especially harmful for our working class and middle-income citizens; people who don’t have the time, money, or resources required to make the low-fat diet work, but care just as much about their health as those in the bubble. For them, we must move on.

I am proposing that our obesity and diabetes epidemics reveal yet another inconvenient truth: our official dietary advice sets most people up for failure. Perhaps Jeb Bush could take a page out of Al Gore’s playbook and put himself on a post–campaign mission to shine a spotlight on this issue. Jeb! has access, he has public speaking skills, he has bank, and, believe it or not, he’s Paleo. Who knew?

If Jeb! were to spread the word, what solutions could he promote? What can any eater do to level the playing field a bit – to have a shot at vibrant health minus the prohibitive price tag of high-maintenance routines?

The Vintage Alternative

I run a small non-profit, Eat the Butter, that is all about real-food-more-fat eating. The main idea behind the site is that the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines have created many of our health problems, and going back to eating the way we used to eat, before they were issued, is a workable solution. The tagline is ‘Vintage Eating for Vibrant Health.’ Specifically, my site suggests some simple ideas about healthy eating. Eat real food. Unrefined. Whole food that has been around for a while. And don’t be afraid to eat more natural fat. To follow this advice, an eater must ignore some of the USDA’s guidelines.  And there are millions of Americans doing just that. (Many of these rogue eaters are affluent, by the way.) I am trying to reach out to more – to every mother. It pains me that millions of mothers are teaching their kids to eat in a low-fat way that is likely to lead, when their kids reach their 30’s or 40’s, down the path of metabolic syndrome, just as it has for us. It is time for a different approach, informed by vintage, time-tested ideas (often backed up by thoroughly modern science) about the basic components of a healthy diet.

And there are millions of Americans doing just that. (Many of these rogue eaters are affluent, by the way.) I am trying to reach out to more – to every mother. It pains me that millions of mothers are teaching their kids to eat in a low-fat way that is likely to lead, when their kids reach their 30’s or 40’s, down the path of metabolic syndrome, just as it has for us. It is time for a different approach, informed by vintage, time-tested ideas (often backed up by thoroughly modern science) about the basic components of a healthy diet.

But can vintage eating be done outside the bubble – even on a budget? It worked pretty well in the 1950’s… why not now?

Sometimes, back-to-basics can actually be pretty affordable… what could be more inexpensive and vintage than a glass of water out of the tap? Think of the groceries you would no longer need: almost all drinks – soda and Snapple and Gatorade and fruit juice (… alas, you might still ‘need’ your coffee and that glass of Chardonnay…); almost all packaged cereals and crackers and chips and snacks; almost all cookies and cereal bars and – God forbid – Pop Tarts. These products all contain highly processed ingredients and are relatively expensive for what you are getting. By buying whole, unprocessed food, the middleman is eliminated and so is his profit margin. Whole foods are usually devoid of packaging or minimally packaged, and don’t typically require an advertising budget. So there are meaningful savings here, especially if you can buy in bulk and shop the sales.

I have lingered in the bubble long enough that saving money in the grocery aisles is not exactly my expertise. My husband, much to his chagrin, can attest to this. I won’t insult you by offering second-hand tips, but there are plenty of smart women blogging about their take on buying high quality food on a budget. By mostly ignoring the packaged goods in the middle of the store, my hope is that you can offset much of the incremental spending you will do on the store’s perimeter: in the produce, dairy, and meat departments. These foods may be somewhat more expensive in general, but offer more nutrition for your food dollar and are more filling in the long run.

Can vintage eating be easy? Yes… perhaps not as easy as a drive-thru, but how long does it take to fry a pork chop? Scramble a couple of eggs? Open a can of green beans? Throw sweet potatoes in the oven? Vintage doesn’t have to be fancy. I bet you cannot drive to pick-up take-out in the time it takes to make a quick vintage meal. Simple vintage meals are the original fast food. Saturated fat is the original comfort food. If only we would give everyone permission to fry up some meat or fish and melt butter on their frozen peas. What a relief it would be for those who have very little slack in their lives and just want easy, satisfying meals that nourish them rather than fatten them.

Can vintage eating be easy? Yes… perhaps not as easy as a drive-thru, but how long does it take to fry a pork chop? Scramble a couple of eggs? Open a can of green beans? Throw sweet potatoes in the oven? Vintage doesn’t have to be fancy. I bet you cannot drive to pick-up take-out in the time it takes to make a quick vintage meal. Simple vintage meals are the original fast food. Saturated fat is the original comfort food. If only we would give everyone permission to fry up some meat or fish and melt butter on their frozen peas. What a relief it would be for those who have very little slack in their lives and just want easy, satisfying meals that nourish them rather than fatten them.

The goal, after all, is not perfection. It is to move in the general direction of whole foods… not to be confused with Whole Foods, the grocery chain, which is definitely not where you want to go if you are on a budget ;-). Give up as many modern, food science inventions as you can stomach, replace them with vintage, whole food, and I bet you will see the ‘always hungry’ status that the processed stuff drives fade. Travel towards vintage eating just as far as your time, tastes, and budget will allow. Then, see how you feel. Even if it doesn’t get you all the way to lean, it might just get you to healthy, which is really what this is about.

References

[i] ‘Walking Tacos’ are a high school snack stand special: open a snack-sized bag of Fritos and toss a couple of spoonfuls of taco meat, shredded lettuce, and grated cheese on top. Yum! Although initially put off by the idea of serving tacos in a foil bag of chips, I have made hundreds on my snack stand shifts and now marvel at the efficiency of this ingenious suburban housewife creation.

[ii] Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The Spread of Obesity in a Large Social Network over 32 Years. New England Journal of Medicine, July 26, 2007. 357-370-9.

[iii] Abedin S. The Social Side of Obesity: You are Who You Eat With. Time, September 3, 2009.

[iv] Puzziferri N. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014 Sep 3;312(9):934-42.

*******************************************************************************

Figures from the author’s comments in the comment section below:

@calihanje, I couldn’t reply to your comment above (I think we nested too much already), so I put my answer here.

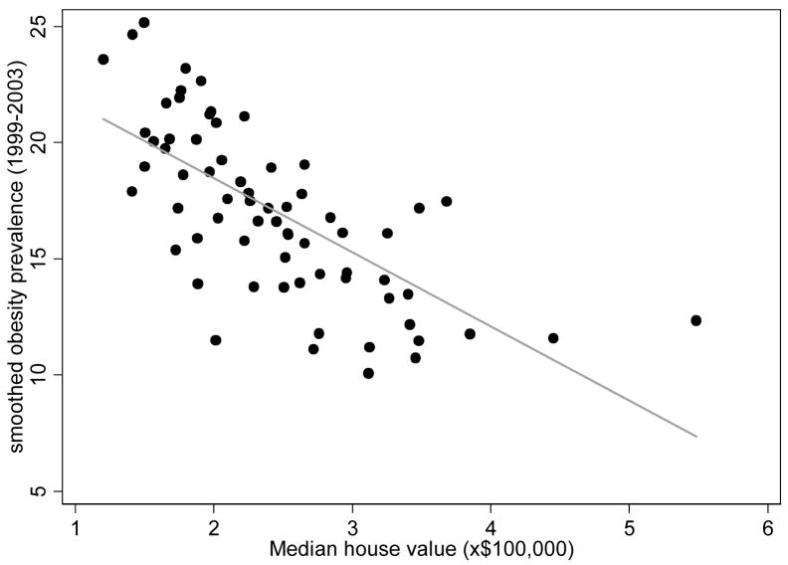

You can find more data (more countries, more detailed breakdowns of income) to see if your impressions hold up. I used Google image with income + obesity. Here are a few I found.

In Canada, there is no trend at all between obesity and income (5 categories of income) when looking at both men and women together.

See table 4.3 here, about three quarters down the page.

http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/publications/diabetes-diabete/facts-figures-faits-chiffres-2011/chap4-eng.php

In Brazil, the trend is similar to the US, that is, rich women are leaner (and only the very richest ones at that), but rich men are fatter.

In the UK, it seems that only the richest women are somewhat leaner (and not that much). No trend for men. Scroll down to see the image of obesity vs. income in this article.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/lifestyle/wellbeing/diet/10525107/Why-is-Britain-fatter-than-ever.html

In Canada again, young adults only. Downward trend for women, upward trend for men.

Scroll down to figure 3.16.

http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cphorsphc-respcacsp/2011/cphorsphc-respcacsp-06-eng.php

On top of contradictory trends, I hope you also notice that obesity is never *rare*, in any income category. It may sometimes be somewhat lower, but money does not guarantee leanness at all.

It seems to me that your “bubble” is more an anecdote than data.

Now, we still have to explain why some zip codes have much less obesity than others. My first guess would be that wealth, neighborhoods and BMI all depend quite a bit on what your parents passed on to you (their money, their origins, and their DNA). Add some spouse selection (rich men marry beautiful (= slim) women) and I think that covers the gender differences.

Maybe you would also be interested in the work of Schelling about segregation. Basically, a slight preference to be surrounded by people like oneself can lead to dramatic differences in neighborhoods.

I think the point of the post was to provide one woman’s observations, not data. Just as one woman’s observations won’t tell the “whole” story, neither will data.

Charlotte Biltekoff’s excellent book, Eating Right in America, has a chapter dealing with the social, cultural, and historical underpinnings of the “obesity epidemic.” She states, “The construction of obesity as a health crisis may have in fact hinged on its historical association with people of color and the poor” (p. 140). Whether real or perceived, the idea of “poor/minority obesity,” according to Biltekoff, has “fed into the stigma at the intersection of race, class, and body size” (p. 141).

Helen Viet notes that this intersection of stigma around race, class, and fatness arose in the early 1900s the the Progressive era, as “Americans made increasingly bold associations between moral righteousness, physical self-discipline, and the unattractiveness of body fat” particularly for women (p. 8). Prior to this time, Viet notes, some body fat was an indication of prosperity [this may still be the case in some cultures]. Thus, as Gloria Steinem pointed out, that which is available to those in power is that which is considered desirable–either fatness or slenderness.

We know there is no question that slenderness is considered more desirable in our current social context; but there are other questions that this discussion then raises for me: Is it really more “available” to those in power (i.e. the very wealthy), or not–and who are the people “in power” here anyway? Or is the concept of obesity as being associated with the poor and with minorities (and where these populations intersect), just that, an association, but not a reality? Or perhaps, in the ever-widening income gap between the 1%ers (or 5%ers) and the rest of America (or the world) is the slenderness of the very rich a way of setting themselves apart from the ever-widening waistbands of even upper/middle income groups?

I will add, that from my reading it seems that, for the very wealthy, the social pressure to maintain a slender body size may be especially intense–particularly for women–and yes, we are talking about white people here because (as Jennifer notes) that’s who the very wealthy disproportionally are.

Charlotte Biltekoff suggests that “one did not need to conduct a survey to see that the affluent upper middle class was terrified of becoming fat and was aware of its social implications, which threatened both race and class status. Fatness remained a marker of inferiority that threatened to strip members of the white, affluent middle class of their class and privilege” (p. 144).

If this is so for the “white, affluent middle class,” how much more so for those in the “bubble”? From Biltekoff’s perspective it seems that it would be a rare thing, in our current moral panic about obesity, to find very many extremely wealthy individuals who are fat.

“In the Third World, the rich are fat and the poor are thin. In the First World, the rich are thin and the poor are fat”.

Some fascinating information here both in the post and in the replies.

I live in a small market town in the UK, surrounded by other small market towns and villages, in an agricultural area. We still have two butchers and two vegetable shops in town, and although many of the village shops have closed they have been replaced by farm shops – in all of them the food is largely traceable, you can find out which farm the produce comes from and even the name – or number – of the specific animal you are eating.

Here the stratification is principally age – the fit healthy old folks who are mainly found in said butchers and veg shops, eating fresh local food, and the middle aged fatties with other metabolic diseases who can be found in the supermarket buying their “low fat!!!” food and becoming inevitably fatter and more ill (this includes several doctors and nurses).

It struck me recently that the people who remember a time BEFORE low fat diets became the default are now dying out, after which Conventional Wisdom will be home free. Most of the “Healthcare Professionals” will never have known a time when there were no “epidemics” of obesity, diabetes and other metabolic diseases.

My mother lived to be 95, her cousins 88 and 91, her own mother 90, a neighbour was 108. Most of my friends, neighbours and relatives thereof who have died made it into at least their eighties, and you can find octogenarians dating back a couple of centuries in the local churchyards. Dig them up and ask them and you would probably get the same answer as from the still living – “None of that low fat rubbish for a start!”

The other side of the coin comes from the farmers. The major crops are wheat, oilseed rape, sugar beet, potatoes, barley and peas for freezing. Carbs and margarine! Yet despite their 400hp tractors, 600hp combines and 30m sprayers there are years when they make a massive loss, wheat may sell for £50/tonne LESS than the cost of production, though they may do well in good years: The profit from these “foods” is all accrued by the middlemen. Which pretty much explains why you are told to eat more of them at the expense of Real Food, the growers of which may not make the same profits but don’t make the huge losses either.

Eating Real Food may initially appear expensive, but it becomes significantly less so when you realise you no longer have to stuff your face with cheap carbs every couple of hours. Add in all the drugs you no longer have to take (antidotes to the diet like statins, BP meds, PPIs etc.) and ensuing medical procedures like stents and amputations, and the fact that you are supporting the local economy rather than shareholders, and you begin to see why the recommendations are what they are and the results are what they are.

The age stratification is interesting. In clinic, when we would put folks on a low-carb diet, they would often say, “Oh you want me to eat like back on the farm!” And yes, I’m afraid those folks are dying out.

Gloria Steinem has an excellent essay published in earlier in the same year the first Dietary Guidelines were released, 1980. She says, “What is rare and possessed only by the powerful is envied as a symbol of power.” In poor societies with little food, plumpness is valued. She goes on to add, “In more fortunate societies where women become plump on starch and sugar if nothing else, leanness and delicacy in women are rare and envied.”

More than once in my recent reading I have come across the statement that, historically, diets of the poor in the U.S. (and perhaps elsewhere) are high in starch, sugar, and fats/oils. Switch out “sugar” for “fruit” and make sure your fats are oil, and you pretty much have the Dietary Guidelines.

I really like your farm-to-pharmacy perspective!

Looking at the input into the system is enlightening.

Many/most of our farms are family owned small businesses. The return on capital they achieve is appalling. The subsidies “paid” to farmers actually go straight to the “Food Industry” in the form of reduced costs. The excess profits made by said “Industry” serve to bankroll dietary authorities, health “charities” and the marketing thinly disguised as “scientific research” they produce. The wheel turns. Any executives of Coke, Kelloggs, Kraft etc. who produced the sort of return on capital taken for granted by farmers would be sacked for gross incompetence.

The drug companies grow rich on producing antidotes to the appalling dietary advice, which gives even more money to back the current Conventional Wisdom and drown out the ever increasing amount of Real Science.

Either you can earn enough to spend enough to overcome the harm – like diabetics who can afford insulin pumps, home gyms and Personal Trainers – or you can subvert The System by reverting to eating what people ate before there were “epidemics” of obesity, diabetes and other metabolic diseases, in the process supporting the local economy free of parasites. That would be nice . . . sorry, am I ranting?

I’ve been doing some reading on the economics of the food system. It’s pretty ugly, especially for the smaller farmers–and it gets worse when you look at it globally. Basically, farmers take the risks and producers make the profits.

And, yes, for consumers there seems to be a similar pattern. The wealthy can make any diet work, and the poor can’t afford any diet but one that will turn you soon enough into a patient. I don’t know what it will take to reverse the process our nutrition guidance and food system have been headed in for the past 40 years, but certainly a rethinking of what a “healthy diet” might be is the place to start.

Ranting welcome. Always.

Yes, both the end users and the producers suffer. A friend was a farmer. He needed a bank loan to renew a load of field drains so he could increase his income back to where he could repay the loan. The bank manager refused. He sold the farm and became a millionaire.

Another, a dairy farmer, said “If I went to my machinery dealer and said “I’m having that tractor, and this is what I’m paying for it!” they would laugh and throw me out of the showroom. Yet that’s what the supermarkets do with my milk.”

A new dairy farm just started up down the road. They put in enough capital so they could deliver their milk direct to local outlets and also process it into cream, cheese and ice cream. That cuts out the middlemen, and their shareholders.

Yet another grew asparagus. He employed East Europeans to harvest it and stored them in caravans, then after the picking season he let the caravans as holiday homes. Then he worked out that he would make more profit letting caravans all year, and the asparagus went away.

A local pub specialised in local food, including stuff he grew and reared himself. He was so successful that the brewery doubled his rent. Most other village pubs that have stayed in business do something similar.

There’s grass roots food as well as grass roots health. And on the other hand there are profits 😦

A doctor who has been using low carb diets for his diabetics claims to save between £10 000 and £30 000/year. Obviously if all doctors did this, drug companies would go bankrupt (I believe there are currently something like 70 “new” diabetes drugs in the pipeline, but next to no new antibiotics). Which is why doctors are tasked NOT to do this.

What we desperately need is evidence-based food and evidence-based medicine – but based on REAL evidence, not thinly disguised marketing. It’s all there, hidden in plain sight on PubMed, and growing exponentially in the last decade or so, and curiously pointing back towards what was known long before “low fat”.

As someone who keeps being tossed into the digital media scholarship pond without a float, I’ve had to temper my optimism that the wealth of information available to the public will somehow accelerate the change I’d like to see. I just have to keep reminding myself, for every person who looks up an actual study on PubMed, there’s five who forward a Food Babe post to all of their friends.

Wow. I’ve been thinking about this post for a week and every time I think I’m ready to comment, I feel like I have to think some more. Enough. Time to talk.

Jennifer, your website looks great and is a welcome addition to what I call the alternative nutrition landscape.

But . . . I’m not sure you see things clearly.

Your post wonderfully points out how Thin is IN. We all know this. And that rich people have it much easier when it comes to being thin.

But thin is not necessarily lean (low or normal body fat) or healthy!

I think you’ve given your crowd on your side of the football field an undeserved halo of health, just because they are thin. How do you know how healthy they really are? Can you see their hypertension, dry skin, high HbA1c, insulin resistance, arthritis, orthodontics, visceral fat, osteoporosis, fatty liver, leaky gut, brain fog, etc?

Sure, perhaps as a group your side of the football field might be relatively more healthy, but going by visible perceptions of weight is a poor marker. There are lots of thin diabetics.

Thin people often have abnormally thin hips and faces/skulls/jaws. After having learned about Weston Price and the healthy wide, broad faces of those cultures who ate traditional non-western diets, I can’t help but think of the poor nutrition that may have contributed to those with abnormally thin faces.

Thin yes, healthy no. We can do better than thin. Focusing on thin or skinny misses the point. Both sides of the football field are so unhealthy.

Hi Kenny, so good to hear from you! It is true that body size and weight are imperfect and often fallible measures of health, but I’m afraid that money buys health too. The “health gap” based on socioeconomic status is, I think, even more distinct that than of weight. WHO puts it succinctly, “Life expectancy is shorter and more diseases are more common further down the social ladder in each society.”

But I think you make a good point about less visible issues. I wonder if the population as a whole–on both sides of the football field–is aging poorly relative to past generations. Life expectancy continues to increase, but I wonder about life quality in later years.

Hi Adele, great to be with you again! 🙂 2015 was tough, but I’m doing well in this new year. Been focused on earning a living, so finding time to read nutrition has been tough, but I’m determined to get back in the saddle!

Well, I am about to disappear into the land of PhD again shortly. I know the feeling of being pulled between the work you “have” to do and the work you “want” to do 🙂

Kenny, I am so glad you posted. You make a good point — thin does not always mean healthy, and you are correct that I have no idea whom among either crowd might have compromised health. In addition, obesity does not always mean ill health, either. Lustig says that 20% of obese adults are metabolically healthy; their weight does not affect their lifespan.

That said, eating higher quality food (especially less processed food), more homemade or homestyle meals, and exercising more all contribute to better health. Trying some alternative diets, like Paleo, low-carb, grain-free or WAPF, should also improve your chances of good metabolic health (IMO). Paying more attention to what you eat (because of the culture of skinny) and having more ways to treat yourself (outside of the food realm) can’t hurt. Finally, bariatric surgery can improve metabolic health. So I think it is fair to say money buys not only thin, but healthy, too.

Here is an article from Diabetes Care, circa 2007. (https://www.researchgate.net/profile/K_M_V_Narayan/publication/255654117_EFFECT_OF_BODY_MASS_INDEX_ON_LIFETIME_RISK_FOR_DIABETES_MELLITUS_IN_THE_UNITED_STATES/links/541abc1a0cf25ebee988bd51.pdf) In essence, 45 year old women who are thin/normal have a 11-14% chance of developing diabetes; overweight women have a 30% chance. Obese women have a 46-62% chance of developing diabetes. So BMI turns out to be a huge risk factor (~4X) for diabetes. I will ask Adele to post the table in the notes — it is broken out by race and gender.

Carb-Loaded is a smart, funny documentary that talks about diabetes risk, even for thin people. You might enjoy it if you haven’t seen it. It skewers the low-fat diet nicely.

I sense you are worried about the people who are getting to thin by eating a very low-fat, almost vegan diet. Although it feels like the opposite of the wisdom of WAPF, I am open to the idea that it may be a healthy path. After all, these diets ditch sugar, white flour, and vegetable oil — three dangerous food types! Denise Minger, typically a high-fat advocate, (she wrote a scathing review of T Colin Campbell’s pro-vegan book, The China Study), has recently blogged about the ‘magic’ of diets with both very low-fat contents and very high-fat contents. She contends that the trouble lies when you are stuck in the middle. You might find her extremely long post interesting. (http://rawfoodsos.com/2015/10/06/in-defense-of-low-fat-a-call-for-some-evolution-of-thought-part-1/) President Clinton’s doctor, Caldwell Esselstyn, published some impressive results with his very-low fat almost vegan regimen in a recent paper. (http://dresselstyn.com/JFP_06307_Article1.pdf) I am openminded, but feel compliance is an issue for many eaters. I’m happy that there is ‘magic’ at the high-fat end of the spectrum, too!

The people who are skinny because of good genes but spend their days eating junk and drinking diet soda are the thin folks I worry about. That holds true on either side of the field, definitely.

Jenni, thanks for the thoughtful reply! Part of me wants to welcome you and part of me wants to see what you’re made of. 😀 Putting your post on Adele’s blog means I’m used to throwing stuff at Adele because I know she can take it and dish it out, and that she’s a smart cookie and been at this a long time, as have I. I’m starting my nineteenth year of low carb eating this year, so I like to think I know a fair bit.

OK, let’s say I accept your thesis that money buys thin/lean/health, then what? Are you going to make everyone rich?

But actually, your alternative path is the primary path that many alternative nutrition plans promote: Just eat real whole food!

Unfortunately, this means you have to learn about food, then Shop/Cook/Clean – all highly inconvenient and fairly incompatible with the way many of us live, or want to live. Can people change their habits to cook more? Yes, but will they long-term? Doubtful. Not when we’re surrounded by endless attractive treats and tasty foods, all promoted by wall-to-wall advertising. That’s partly why I try to never watch TV commercials.

From my own experience, I know that I won’t consistently do the Shop/Cook/Clean, no matter what the promised benefits are. I’ll find other ways to get much of the benefits without all the work.

As for Denise Minger. I’ve read her book and it’s good. But I think she continues to believe too much in nutrition epidemiology and her ability to tell the “good” studies from the bad ones. Except they’re all bad. See Alice and Fred’s discussion of the tragedy of the “new epidemiology”, http://ketopia.com/new-epidemiology/

And vegan diets? I don’t understand how you get around the fact that they lack some essential nutrients, and that no native indigenous peoples have ever been found to be exclusively vegetarian, let alone vegan. I prefer to eat the most concentrated nutrients I can, which means focusing on meats and fats. Vegetarian and vegan diets usually mean high-carb diets, which will rot your teeth, as Denise Minger learned. Leaving proteins and fats on your teeth won’t rot them. What’s good for your teeth is probably good for the rest of your body.

Finally, a request if I might. I looked through your website and really enjoy the visuals. But what I think would really help is a deeper section on who you are and why you care about this issue. What’s your story? That’s what I always look for and didn’t find, and I think that’s what people really want to know before they start believing you care. A few months ago, Nina Teicholz somehow stumbled across my tiny obscure blog and sent me a nice note asking me what’s my story. She wanted to know because she said I had some good info on the blog. It made my day. 🙂

Hello again. Unfortunately, I will never be as smart or funny (or as tough) as Adele, but that does not mean we can’t have a constructive back-and-forth! And I do feel welcomed — thanks for checking out my site. What is your blog called? I would like to reciprocate.

Thanks for the article link. It was good. I have used ice cream consumption rates and drownings to illustrate the correlation/causation point, but skirts and breast cancer is a better way to say it.

Your “Madam, I’m sorry your first choice…” quote made me laugh. Alas, everyone can’t have endless time and money for eating right and exercising. That was part of the point of the post, as I am sure you are aware. What I am trying to do with ‘Vintage Eating’ on Eat the Butter is to repackage alternative (mostly ancestral) eating ideas into something a non-food and non-science oriented mother might find appealing and approachable. I have no ‘scientific chops’ but I am trying to bring what I do have: complete confidence in the ancestral perspective, a decent sense of what it is like to cook for kids for 20+ years, an ability to curate others’ ideas, an informed perspective on how corporate interests come into play, an ability to express myself, and a modest budget for trying to say what I have to say to as many mothers as possible. A rising tide floats all boats, so I hope Eat the Butter can bring more mothers to the real-food-more-fat table, and that that will be good for the community of experts selling more detailed plans and cookbooks.

Many mothers are busting it to make low-fat meals for their families. If we could just get them to flip the ‘fat is bad’ script in their heads to ‘sugar is bad,’ all that work they are already doing would pay much greater dividends. Breakfast is an obvious example. If Special K, skim milk, and orange juice could no longer be sanctified as the epitome of a healthy breakfast, there are lots of moms who would be willing to spend 4 minutes frying an egg. Mothers are pretty motivated to do what is best for their children; we just need to redefine ‘best.’

Author and science journalist Ann Gibbons is a personal friend; her thoughts have influenced my willingness to accept that many ancestral diets contain a lot of starch. Check out her National Geographic piece, The Evolution of Diet, here: (http://www.nationalgeographic.com/foodfeatures/evolution-of-diet/) We know that meat was often scarce — so an almost vegan diet doesn’t seem completely anti-ancestral to me.

We also know that almost vegan diets, when compared to standard low-fat diets, protect against obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Might they increase cancer or depression or stroke? I have no idea. I am committed to spreading the word about real-food-more-fat, not opining on all dietary options. So, as I said, I have an open mind about those who choose to minimize animal products for various reasons. And, as you point out, I hope they are supplementing those missing essential nutrients carefully.

As far as more about me on the site, I’ll try to do that. I have heard that from others, too, and I know people connect more when they hear your story. Perhaps I hesitate because I ‘forgot to have a career.’ It is probably my own insecurity, but I fear that people dismiss the thoughts of long-term stay-at-home moms, even if they have impressive educations (and thus once had a competitive voice)… makes me hesitate to emphasize my story, I guess.

I wouldn’t worry too much about not working. I spent a decade being essentially a bum with internet access (so I could read and learn about nutrition). I have no formal education in nutrition whatsoever, just an intense interest.

From your website and your post and comments here, I can see that you have the skills needed, namely, good communication and writing skills, along with good public speaking skills. And by your appearance on Adele’s blog, you know how to make connections with the right people.

As for my blog, just click on my name at the top of this message or any of my posts here.

For telling your story, all I’m really looking for is what made you change to the way you eat now? When? Why? What was your eating pattern before? What made you change? What benefits do you get from the way you eat now? How did you discover a better way of eating? What was the transition like? Who did you learn from and what lessons have you learned? Was it easy or hard? Was it worth it? Why? That kind of stuff.

In brief, I started strictly following the Food Pyramid in the mid-90s. I wasn’t even trying to lose weight; I just wanted to eat healthier. Well, the low-fat diet turned me into a pre-diabetic with insatiable hunger, unquenchable thirst, extremely dry skin, among other maladies. I said to myself, this can’t be right, and searched for a better way, eventually finding the Protein Power book and the low carb way of eating. Low carbing was a revelation, as it cured all my ills and made me feel so much better. There were so many predictions that low carb diets might work for short-term weight loss, but surely you were just asking for heart disease later. Well, it’s later now, and I’m fine, so all that saturated fat hasn’t managed to kill me yet.

Jenni, I agree with Kenny about hearing more about “your story.” I know (at least part of) it, and I think it would make for very interesting material. You have a unique perspective on this matter, as your post demonstrates.

Yes agreed. Genealogical research shows that one side of my family is bimodal, there are all these healthy long-lived folks and the others, like me, who remain skinny but have all the metabolic defects of obesity. It’s known as “skinny fat”, Michael Eades has called it “metabolic obesity” and someone (can’t remember who) called it “lipodystrophy lite” in that we go through all the steps of gaining weight except for stashing the excess food in our fat cells, so our blood remains full of excess glucose, insulin and lipids and we get hypertension too.

It took real dedication from a dietician, carefully deleting all fat from my diet and replacing it with “healthy” carbs, before I finally gained weight so she could then accuse me of “failing to comply” with the diet.

There are similarities with MODY forms of diabetes except the distribution within the family, it strikes mainly but exclusively males who die prematurely, as I will, from CVD.

I spent decades wrecking myself with excess carbs and dutifully eating “low fat” just as I was instructed. Meanwhile all my symptoms of diabetes and diabetic complications were written off as psychiatric in origin or completely made up. I was over fifty when a GP finally thought to check my postprandial blood glucose. I’ve spent the last decade or more keeping my BG, BP and lipids in check by eating the exact opposite of what I was told, and been so successful I was recently told there was never anything wrong with me. Of course my premature death will be blamed on the years when I ate “too much fat” and not enough starch, and the decades when I ate too many carbs will be ignored.

Estimates are that 5 – 20% of “Type 2” diabetics are non-overweight, the real number will never be known so long as doctors believe the same as the rest of the public, that diabetes is caused by being fat and obesity is caused by eating fat. I know enough people with a similar syndrome to suspect the 20% figure may be accurate.

The other side of the coin is that some of the plumper people in the family were healthier, again not uncommon.

Joseph Kraft understood all this decades ago, but how many current doctors have ever heard of him, let alone John Yudkin, Peter Cleave, Weston A Price and many others whose work was bulldozed out of sight by Ancel Keys and the Lipid Hypothesis/Diet-Heart Hypothesis?

Chris, your personal story is a compelling one. Type 2 diabetes is exploding, and although it is much more common in people carrying extra weight, everyone should be looking for it. Blood sugar meters cost $10 on Amazon, and strips are about 17 cents each… so in theory, we all should be able to test our fasting blood sugar and our postprandial (after a meal) blood sugar. The fact that there are 77 MILLION Americans walking around with undiagnosed prediabetes is shocking. Time for some community screenings, don’t you think? Perhaps we need to start ignoring our ineffective federal health initiatives and going local with solutions.

I am so glad you have identified your health issue and taken steps to minimize the damage. Thank goodness you have the confidence to eat pretty much the opposite of what you are told to eat. Here’s to many more low-carb years!

Sadly, there is already a move afoot to increase screening for undiagnosed diabetes–all the better to get folks on meds and a low-fat diet right away!

I wonder how we could flip that script? As in, the ADA’s script of heavy reliance on drugs to control blood sugar in prediabetics and type 2 diabetics rather than diet…and providers’ tendencies to ignore the ADA approved low-carb option and go straight to the ‘moderate, balanced diet’ approach (plus Metformin, of course). This ADA article from 2011 reveals their confusion… (http://www.diabetesforecast.org/2011/mar/are-carbs-the-enemy.html) Have they made any progress in the last five years? What could get them to make progress?

I think where this is another area where it is going to take patients educating their healthcare providers for things to change–rather than the other way around (the comments to the article you linked are pretty telling). MDs, RNs, RDs hold onto what they’ve learned during their training. Any “new” information is typically suspect–a “fad” or worse. And then there are the ideological commitments which supersede individualized care. Only patients advocating for themselves can change that.

Reading their own forums for a start! They are surprisingly full of success stories, as are almost all diabetes forums, newsgroups and blogs, yet none of the successes follow the ADA diet.

When John Buse was in charge, they backpedalled slightly on their diary recommendations and lost one or two major sponsors. They haven’t done that since.

Around the same time this happened

http://carbwars.blogspot.co.uk/2010/05/so-close.html

Meanwhile patients continue to produce 5 – 8% and sometimes over 10% improvements in A1c, let alone all the other improvements in weight, lipids, BP etc. while the ADA and all other national diabetes “charities” flog ever more expensive drugs from their sponsors which may produce 2% or less improvement at the expense of often horrendous side effects including but not limited to premature death.

I second the “read their own forums” bit! It is really a little weird, isn’t it?

I met Judy Barnes Baker when she was going through all that. So close.

It is FOUND more often in overweight people because that’s where doctors have been trained to look.

Policy here is to refuse meters and test strips to all but Type 1 diabetics and Type 2s when they get on insulin. Current policy also is to use ONLY A1c for diagnosis. As Any Fule Kno this produces a high level of underdiagnosis, which improves statistics but does naff all for the patients’ health.

Even more compelling would be to look at insulin levels which often go south years before the BG is affected, and even more years before fasting BG or A1c are affected.

Many doctors see diabetes as “always progressive” without understanding that it’s the treatment rather than the disease which causes the progression, so they see little point in early diagnosis. Then when they see successful patients they warn them about the “extreme dangers” of cranks on the internet telling them to eat more arterycloggingsaturatedfat and less starch. What, Ron Krauss, past president of the American Heart Association, is a CRANK???

To be fair it isn’t really the doctors’ fault, they believe the dogma they have been fed and have no clue that alternatives not only exist but are documented in studies they are not told about.

Thinking about it further, I was a victim of “you’re thin so you can’t be ill” syndrome, which is far from uncommon, though less common than the corollary “if you just lose some weight you’ll get better” syndrome.

“You’re losing weight nicely!” may mean you ARE losing weight nicely, or it may mean you have terminal cancer, or adult onset Type 1/LADA and are pissing your body down the toilet.

“Your LDL/cholesterol is coming down nicely!” may mean your diet is working or it may mean (as I found out last year) you have become hypERthyroid. Who knew that hyperthyroid would produce exactly the same drop in LDL as a statin?

There needs to be a more nuanced return to looking at the “whole picture” rather than just seeing the end result of tests as indicating a drug deficiency.

Attia touches on this in his TED MED — (https://www.ted.com/talks/peter_attia_what_if_we_re_wrong_about_diabetes?language=en) According to him, the lean with insulin resistance are more likely to progress to more serious illnesses than the obese with insulin resistance. So although excess weight makes you much more likely to have insulin resistance, he muses that perhaps weight gain might be the healthiest response to insulin resistance — as in, if you already have insulin resistance, your odds are worse if you are thin, because your body hasn’t figured out the least damaging way to deal with that. Interesting.

It is so hard to understand the resistance in the community of diabetic doctors to a low-carb option. Although it may not be for everyone, to not offer it up as an alternative worth trying seems crazy to me. Some patients would rather give up carbs than have their disease progress. They should be encouraged to do so, not kept in the dark.

The dogma states that diabetes is caused by being fat, and being fat is caused by eating fat. So “obviously” a low fat diet is the cure.

When it inevitably fails the response is usually that patients are “failing to comply” or that “diabetes is always progressive” and the only answer is adding more meds to the more starch.

Not surprising when you look at the sponsors of the ADA, AHA, AND and all equivalents in all other countries – they are mostly drug companies, margarine manufacturers and carbohydrate processors. Busy GPs rely on what these people feed them in the guise of “Evidence Based Medicine” and they literally have no clue as to what is hidden in plain sight on PubMed – unless they actually go look for themselves, and when you are beset on one side by increasing numbers of patients and on the other increasing numbers of accounting clerks and their Rules, where do you find time to read stuff you didn’t know was there?

Peter at Hyperlipid

http://high-fat-nutrition.blogspot.co.uk

has some interesting stuff about “Physiological Insulin Resistance” if you look in the sidebar. The picture I have is that IR evolved as an adaptive mechanism for nutrient partitioning and food storage, but that only works when it is subsequently switched off again so the stored food (body fat) can be metabolised – which never happens on a high carb low fat diet. This ties in neatly with Peter Attia. Leptin is also a major player and triglycerides (from excess carbs) block leptin from crossing the blood-brain barrier so the hypothalamus no longer sees the leptin signal telling you you have eaten enough and gotten fat.

I have another theory too, that skinny people psychically transfer their excess weight to other folks who get fat without eating any more, but the nurse is coming by with my medication soon.

The overconfidence/dogma at the top (ADA, etc.) is a big part of the problem… Thanks for the link to Hyperlipid link — a very interesting (and detailed) blog.

Maybe we could psychically transfer the message that the ADA should indeed read its own forums. It seems like the cardiologists are better at this — that is, learning from their patients. So happy to hear Dr. Steven Nissen (head of cardiology at Cleveland Clinic) break ranks so publicly last month. The DGA as an ‘evidence free zone.’ He is not mincing words.

Great article and comments! I’ve learned and enjoyed them all, and I especially like Stephen’s second paragraph.

However, I think one glaring fact missing from this conversation is our government’s and universities’ agricultural policies. They encourage the production of all types of sugar but not vegetables. They think GMO foods and those sprayed with pesticides and herbicides are ok or, even good, to eat. The policies are based on a river of oil and not a full understanding of the biology in the soil. All of these have reduced the nutrition of our food and the health of our soils. We need healthy soils to optimize the nutrition of our food and, as a wonderful side effect, to sequester lots of carbon.

And again, the richer of those among us will be able to more easily access those foods that have been grown in ways that improve its nutrition. These foods are more expensive and may only be available at farmers’ markets that are open during limited times and places. Thus, the farmers’ markets take more time and effort from which to purchase food.

Many people and organizations are promoting better agricultural practices, which are actually regenerative agriculture. Some of these people include Elaine Ingham, Allan Savory, Joel Salatin, Greg Judy, Guy Brown and last but not least Ray Archuleta. Some organizations include Westin A Price, Paleo groups as a whole, many small farmer groups and the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. Yeah, one government group is amazingly flying counter to the established wisdom of the most powerful and thus influential. Here’s a 24 minute NRCS’s video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9uMPuF5oCPA

Oooh. I got to see Ray Archuleta speak recently. Boy, if I weren’t already doing what I’m doing, I would want to be a soil scientist!

And about the USDA: it’s a huge agency. There are a number of within the agency where valuable work is being done; the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, however, is not one of them.

Man, am I jealous or what? I would love to see Ray give a talk in person. Watching him in the videos, he seems like a force of nature. I mean how can a bureaucratic in the middle of the second largest bureaucracy in America (our military is the first) have such a strong voice.

By the way, I messed up. It is Gabe Brown not Guy. He started to practice some of the regenerative agriculture practices 20 years ago in North Dakota (brrrr). His motto is something like: we mimic nature so that she does most of the work and we then can sign the back of the check and not the front.

One great example of the power of mimicking nature is his production of corn. He produces about 140 bushels per acre in the short ND summer with an average annual rainfall of 11 inches and no irrigation. While a visiting farmer from Missouri, produced only a little more per acre, but has a longer growing season and over 40 inches of rain per year and yet had to pay to irrigate his fields. So, yes, soil science is where it is at now!

Oh and his friend runs a laboratory that works with farmers. He did not believe all of the hype that Gabe was saying. So, he personally came and sampled and tested Gabe’s corn. Yeah, it was chock full of all of the corn nutrients.

Here’s one of his talks: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9yPjoh9YJMk

Also Elaine Ingham’s first hour long talk in the following 3 hour video is great. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMvpop6BdBA No fertilizer is necessary with truly healthy soil.

Not to up the jealousy quotient, but I got to see both Gabe Brown & Alan Savory live and in person 🙂 [The alt-ag equivalent of Bruce Springsteen-Elvis Costello double bill.] I hang out with the right crowd.

An unresolved tension in the local/sustainable foods movement is that whole local foods include animal products–because as Ray Archuleta is fond of saying (from Howard?): “Mother Nature never farms without livestock.” But then, the logical thing to do is to include them in the FOOD system as well, which goes in opposition to both health claims and moral stances held by many otherwise “back to nature” local/sustainable advocates.

Thanks for the links!

Well now I just in awe. Good on you. And I like that “Mother Nature never farms without livestock.”

I think Valerie’s comment came closest to capturing my unease at this guest post. Structural inequalities and stigma, whether it be towards race, class (and yes, that includes the US), or weight is a major, chronic life stressor. Let me speak to the scientist in you – bodily response, more cortisol. More cortisol, more central adiposity. More stigma, more prejudice, more inflammation, more diabetes, more hypertension, more heart disease. And while I know that is not the sole answer to the differences between the home and away teams, the tone of this article struck me as rather patronising, and attached to a hefty saviour complex, without the insight I usually associate with this blog. I’m surprised that Adele signed off on this to be honest. While some of the points made are no doubt valid, this left me with a really sour taste in my mouth.

It’s a difficult subject to discuss, and Jennifer and I went through a lot of back and forth about it. She will be the first to admit that from her “bubble,” the desire to “help” does indeed seem patronizing (I appreciate her honesty in telling the story about attending a workshop on obesity and food deserts–an event that would likely be limited to those with the time and resources to devote to such unpaid endeavors, but who “care.” I think she skewers her own earnestness in this regard very nicely: “Boy, were we – visitors to this world – going to prove that even in a food desert and on a budget, healthy eating was possible if we made wise choices.”) At the same time, I can assure you that our current public health nutrition programs for low-income communities come off as nothing more than “let’s convince poor people to eat like rich people” with exactly zero attention to the complexity of other issues that go into, not just eating, but as you pointed out, what your body does with the food you eat.

I think you make a terrific point about cortisol, and one that is seldom explored in the scientific literature. As I mentioned to Valerie, I have some comments of my own to make in regard to her post, and one of them is about stress. To take one of Jennifer’s examples, if you’re the mom trying to decide between oatmeal (kids will not cheer) and Sugar Bombs (kids will smile and hug you), not only might you choose the latter for the reasons she mentions, but imagine the stress that goes into just having to make that decision. You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t. Argue with kids? Guilt? Pick one. A recent dissertation at my university discusses how mothers must negotiate food-health decisions as they raise their children, and again, it seems to almost go without saying that for low-income mothers, such negotiations are circumscribed by very different concerns, ones over which they have less control, than they are for higher-income mothers. Lack of control, stress, cortisol–it’s all of a piece.

In other words, I think you are highlighting one of the biological factors that goes hand-in-hand with structural inequalities and can contribute to poor health. Jennifer is highlighting sociocultural factors. Daisy Zamora, a PhD in nutrition epidemiology who has done some outstanding work on racial differences in response to dietary patterns, highlighted those factors. None of them provide a complete picture, as you noted. But we need to start thinking of these things as all inter-related. I don’t want poor health in any population attributed to cortisol and then “treated” with medications that reduce that particular hormone without any consideration of why that population may have higher levels of cortisol in the first place.

Most of all, I think we need to keep the discussion going and open. Jennifer’s willingness to say what things look like from her place in the world is a welcome antidote to articles like this one in the Washington Post, Why we can’t get our obesity crisis under control, which suggests that the opposition that low-income and minority communities have to taxing “junk food” is nothing short of self-harm which policymakers should override. There’s no consideration of either biological or sociocultural issues that may be at play: hunger, stress-relief through food, convenience, dissimilar values about what constitutes a happy life.

I’ll have more to say about this. Thanks for joining the conversation.

Adele, my upbringing was poor working class, although with a good work ethic and strong principles. I thought the article was sensitive and insightful. Yes, it was a perspective from the other side of the rails, but Jennifer’s entitled to her say and I’m grateful that she tackled a sensitive subject with obvious kindness and a desire to help. I’d have a slightly different perspective, but I agreed with pretty much all of her article. We shy away from these subjects too often to avoid reactions such as Angela’s, which I think is overly sensitive.

The working class were told for years to avoid fat and gradually did so, and now it’s sugar, with much better evidence. It will take much longer for the message to get through because the working class have less time and inclination to read health messages and more reliance on the Government. I think there’s also more short term thinking. If life’s grim, what’s good now has more appeal. Those with a long and comfortable life ahead of them tend to want to protect it and see the benefit of delayed gratification. Confidence is another issue. If you really think you know what you’re talking about, you’ll be stronger with your children and that tends to be the middle classes. However, poor people often have a lot more contact with Government and in the dietary field that’s disastrous. The dietary guidelines hit them the hardest.

The last conversation I had with a nurse on nutrition resulted in her taking notes and borrowing my books. More commonly for the poor or working class, it’s to be on the receiving end of terrible advice.

Jennifer has written an excellent article and provided links to a website that I found particularly useful. Poor people don’t need shielding from the truth and they don’t have a fit of the vapours when they hear it.