Nostalgia for a misremembered past is no basis for governing a diverse and advancing nation.

The truth is that I get most of my political insight from Mad Magazine; they offer the most balanced commentary by far. However, I’ve been very interested in the fallout from the recent election, much more so than I was in the election itself; it’s like watching a Britney Spears meltdown, only with power ties. I kept hearing the phrase “epistemic closure” and finally had to look it up. Now, whether or not the Republican party suffers from it, I don’t care (and won’t bother arguing about), but it undeniably describes the current state of nutrition. “Epistemic closure” refers to a type of close-mindedness that precludes any questioning of the prevailing dogma to the extent that the experts, leaders, and pundits of a particular paradigm:

“become worryingly untethered from reality”

“develop a distorted sense of priorities”

and are “voluntarily putting themselves in the same cocoon”

Forget about the Republicans. Does this not perfectly describe the public health leaders that are still clinging blindly to the past 35 years of nutritional policy? The folks at USDA/HHS live in their own little bubble, listening only to their own experts, pretending that the world they live in now can be returned to an imaginary 1970s America, where children frolicked outside after downing a hearty breakfast of sugarless oat cereal and grown-ups walked to their physically-demanding jobs toting homemade lunches of hearty rye bread and shiny red apples.

Remember when all the families in America got their exercise playing outside together—including mom, dad, and the maid? Yeah, me neither.

So let me rephrase David Frum’s quote above for my own purposes: Nostalgia for a misremembered past is no basis for feeding a diverse and advancing nation.

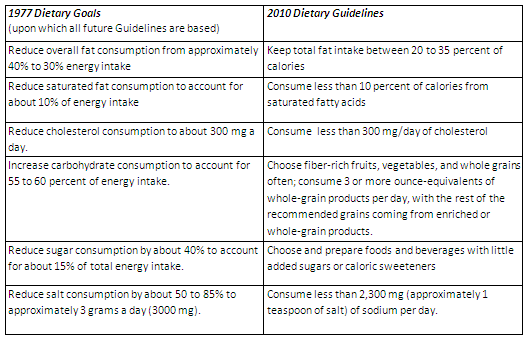

If you listen to USDA/HHS, our current dietary recommendations are a culmination of science built over the past 35 years on the solid foundation of scientific certainty translated into public health policy. But this misremembered scientific certainty wasn’t there then and it isn’t here now; the early supporters of the Guidelines were very aware that they had not convinced the scientific community that they had a preponderance of evidence behind them [1]. Enter the first bit of mommy-state* government overreach. When George McGovern’s (D) Senate Select Committee came up with the 1977 Dietary Goals for Americans, it was a well-meaning approach to not only reduce chronic disease, a clear public health concern, but to return us all to a more “natural” way of eating. This last bit of ideology reflected a secular trend manifested in the form of the Dean Ornish-friendly Diet for a Small Planet, a vegetarian cookbook that smushed the humanitarian and environmental concerns of meat-eating in with some flimsy nutritional considerations, promising that a plant-based diet was the best way to feed the hungry, save the planet, safeguard your health, and usher in the Age of Aquarius. This was a pop culture warm-fuzzy with which the “traditional emphasis on the biochemistry of disease” could not compete [2].

If you listen to some folks, the goofy low-fat, high-carb, calories in-calories out approach can be blamed entirely on this attempt of the Democrats to institutionalize food morality. But, let’s not forget that the stage for the Dietary Guidelines fiasco was set earlier by Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz, an economist with many ties to large agricultural corporations who was appointed by a Republican president. He initiated the “fencerow to fencerow” policies that would start the shift of farm animals from pastureland to feed lots, increasing the efficiency of food production because what corn didn’t go into cows could go into humans, including the oils that were a by-product of turning crops into animal feed. [Update: Actually, not so much Butz’s fault, as I’ve come to learn, because so many of these policies were already in place before he came along. Excellent article on this here.]

When Giant Agribusiness—they’re not stupid, y’know—figured out that industrialized agriculture had just gotten fairydusted with tree-hugging liberalism in the form of the USDA Guidelines, they must have been wetting their collective panties. The oil-refining process became an end in itself for the food industry, supported by the notion that polyunsaturated fats from plants were better for you than saturated fats from animals, even though evidence for this began to appear only after the Guidelines were already created and only through the status quo-confirming channels of nutrition epidemiology, a field anchored solidly in the crimson halls of Harvard by Walter Willett himself.

Between Earl Butz and McGovern’s “barefoot boys of nutrition,” somehow corn oil from refineries like this became more “natural” than the fat that comes, well, naturally, from animals.

And here we are, 35 years later, trying to untie a Gordian knot of weak science and powerful industry cemented together by the mutual embarrassment of both political orientations. The entrenched liberal ivory-tower interests don’t want look stupid by having to admit that the 3 decades of public health policy they created and have tried to enforce have failed miserably. The entrenched big-business-supporting conservative interests don’t want to look stupid by having to admit that Giant Agribusiness, whose welfare they protect, is now driving up government spending on healthcare by acting like the cigarette industry did in the past and for much the same reasons.

These overlapping/competing agendas have created the schizophrenic, conjoined twins of a food industry-vegatarian coalition, draped together in the authority of government policy. Here the vegans (who generally seem to be politically liberal rather than conservative, although I’m sure there are exceptions) play the part of a vocal minority of food fundamentalists whose ideology brooks no compromise. (I will defend eternally the right for a vegan–or any fundamentalist–to choose his/her own way of life; I draw the line at having it imposed on anyone else–and I squirm a great deal if someone asks me if that includes children.) The extent to which vegan ideology and USDA/HHS ideology overlap has got to be a strange bedfellow moment for each, but there’s no doubt that the USDA/HHS’s endorsement of vegan diets is a coup for both. USDA/HHS earns a politically-correct gold star for their true constituents in the academic-scientific-industrial complex, and vegans get the nutritional stamp of approval for a way of eating that, until recently, was considered by nutritionists to be inadequate, especially for children.

Like this chicken, the USDA/HHS loves vegans—at least enough to endorse vegan diets as a “healthy eating pattern.”

But if the current alternative nutrition movement is allegedly representing the disenfranchised eaters all over America who have been left out of this bizarre coalition, let us remember that, in many ways, the “alternative” is really just more of the same. If the McGovern hippies gave us “eat more grains and cereals, less meat and fat,” now the Republican/Libertarian-leaning low-carb/primaleo folks have the same idea only the other way around—and with the same justification. “Eat more meat and fat, fewer grains and cereals;” it’s a more “natural” way to eat.

As counterparts to the fundamentalist vegans, we have the Occupy Wall street folks of the alternative nutrition community—raw meaters who sleep on the floor of their caves and squat over their compost toilets after chi running in their Vibrams. They’re adorably sincere, if a little grubby, and they have no clue how badly all the notions they cherish would get beaten in a fight with the reality of middle-Americans trying to make it to a PTA meeting.

To paraphrase David Frum again, the way forward in food-health reform is collaborative work, and although we all have our own dietary beliefs, food preferences, and lifestyle idiosyncrasies, the immediate need is for a plan with just this one goal: we must emancipate ourselves from prior mistakes and adapt to contemporary realities.

Because the world in which we live is not the Brady Bunch world that the many of us in nutrition seem to think it is.

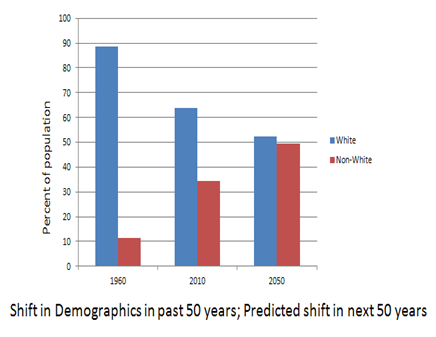

Frum makes the point that in 1980, when the Dietary Guidelines were first officially issued from the USDA, this was still an overwhelmingly white country. “Today, a majority of the population under age 18 traces its origins to Latin America, Africa, or Asia. Back then, America remained a relatively young country, with a median age of exactly 30 years. Today, over-80 is the fastest-growing age cohort, and the median age has surpassed 37.” Yet our nutrition recommendations have not changed from those originally created on a weak science base of studies done on middle-aged white people. To this day, we continue to make nutrition policy decisions on outcomes found in databases that are 97% white. The food-health needs of our country are far more diverse now, culturally and biologically. And another top-down, one-size-fits-all approach from the alternative nutrition community won’t address that issue any more adequately than the current USDA/HHS one.

For those who think the answer is to “just eat real food,” here’s another reality check: “In 1980, young women had only just recently entered the workforce in large numbers. Today, our leading labor-market worry is the number of young men who are exiting.” That means that unless these guys are exiting the workforce to go home and cook dinner, the idea that the solution to our obesity crisis lies in someone in each American household willingly taking up the mind-numbingly repetitive and eternally thankless chore of putting “real food” on the table for the folks at home 1 or more times a day for years on end—well, it’s as much a fantasy as Karl Rove’s Ohio outcome.

David Frum points out that “In 1980, our top environmental concerns involved risks to the health of individual human beings. Today, after 30 years of progress toward cleaner air and water, we must now worry about the health of the whole planetary climate system.” Today, our people and our environment are both sicker than ever. We can point our fingers at meat-eaters, but saying we now grow industrialized crops in order to feed them to livestock is like saying we drill for oil to make Vaseline. The fact that we can use the byproducts of oil extraction to make other things—like Vaseline or livestock feed—is a happy value-added efficiency in the system, no longer its raison d’etre. Concentrated vertical integration has undermined the once-proud tradition of land stewardship in farming. Giving this power back to farmers means taking some power away from Giant Agribusiness, and neither party has the political will to do that, especially when together they can demonize livestock-eating while promoting corn oil refineries.

And it’s not just our food system that has changed: “In 1980, 79 percent of Americans under age 65 were covered by employer-provided health-insurance plans, a level that had held constant since the mid-1960s. Back then, health-care costs accounted for only about one 10th of the federal budget. Since 1980, private health coverage has shriveled, leaving some 45 million people uninsured. Health care now consumes one quarter of all federal dollars, rapidly rising toward one third—and that’s without considering the costs of Obamacare.” That the plant-based diet that was institutionalized by liberal forces and industrialized by conservative ones is a primary part of this enormous rise in healthcare costs is something no one on either side of the table wants to examine. Diabetes—the symptoms of which are fairly easily reversed by a diet that excludes most industrialized food products and focuses on meat, eggs, and veggies—is the nightmare in the closet of both political ideologies.

David Frum quotes the warning from British conservative, the Marquess of Salisbury, “The commonest error in politics is sticking to the carcass of dead policies.”

Right now, it is in the best interest of both parties to stick to our dead nutrition policies and dump the ultimate blame on the individuals (we gave you sidewalks and vegetable stands–and you’re still fat! cry the Democrats; we let the food industry have free reign so you could make your own food choices–and you’re still fat! cry the Republicans). It’s a powerful coalition, resistant to change no matter who is in control of the White House or Congress.

What can be done about it, if anything? To paraphrase Frum once again, a 21st century food-health system must be economically inclusive, environmentally responsible, culturally modern, and intellectually credible.

We can start the process by stopping with the finger-pointing and blame game, shedding our collective delusions about the past and the present, and recognizing the multiplicity of concerns that must be addressed in our current reality. Let’s begin by acknowledging that—for the most part—the people in the spotlight on either side of the nutrition debate don’t represent the folks most affected by federal food-health policies. It is our job as leaders, in any party and for any nutritional paradigm, to represent those folks first, before our own interests, funding streams, pet theories, or personal ideologies. If we don’t, each group—from the vegatarians to folks at Harvard to the primaleos—runs the risk of suffering from its own embarrassing form of epistemic closure.

Let’s quit bickering and get to work.

**********************************************************

*This was too brilliant to leave buried in the comments section:

“Don’t you remember the phrase “wait til your father gets home”? You want to know what the state is? It’s Big Daddy. Doesn’t give a damn about the day to day scut, just swoops in to rescue when things get out of hand and then takes all the credit when the kids turn out well, whether it’s deserved or not. Equates spending money with parenting, too.”–from Dana

So from henceforth, all my “mommy-state” notions are hereby replaced with “Big Daddy,” a more accurate and appropriate metaphor. And I never metaphor I didn’t like.

References:

1. See Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs of the United States Senate. Dietary Goals for the United States. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1977b. Dr. Mark Hegsted, Professor of Nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health and an early supporter of the 1977 Goals, acknowledged their lack of scientific support at the press conference announcing their release: “There will undoubtedly be many people who will say we have not proven our point; we have not demonstrated that the dietary modifications we recommend will yield the dividends expected . . . ”

2. Broad, WJ. Jump in Funding Feeds Research on Nutrition. Science, New Series, Vol 204. No. 4397 (June 8, 1979). Pp. 1060-1061 + 1063-1064. In a series of articles in Science in 1979, William Broad details the political drama that allowed the “barefoot boys of nutrition” from McGovern’s committee to put nutrition in the hands of the USDA.

Stacia Nordin RD combines her nutrition expertise with permaculture knowledge and the desire to end hunger in Malawi, Africa in a socially, environmentally, and nutritionally sustainable way.

Stacia Nordin RD combines her nutrition expertise with permaculture knowledge and the desire to end hunger in Malawi, Africa in a socially, environmentally, and nutritionally sustainable way.

Franziska Spritzler RD CDE is applying her nutrition expertise to specifically help patients with diabetes (CDE stands for Certified Diabetes Educator). As Type 2 diabetes has reached epidemic proportions in this country and across the globe, we seem to have forgotten that it is designated in

Franziska Spritzler RD CDE is applying her nutrition expertise to specifically help patients with diabetes (CDE stands for Certified Diabetes Educator). As Type 2 diabetes has reached epidemic proportions in this country and across the globe, we seem to have forgotten that it is designated in